Shades of Nixon: why Trump must tread carefully in the swamp

Niall Ferguson says Trump has one big advantage over Nixon: Republicans have a majority in all seats of government, and that is where the real power lies

The US president has declared war on the press. He cannot forgive the media for saying the crowd at his inauguration was small. He is even picking fights with a comedy show. His press secretary is a laughing stock. Worse, the president is trying to pick and choose between news outlets, excluding some from briefings. And he is trying to deflect criticism by accusing his predecessor of having tapped his telephone.

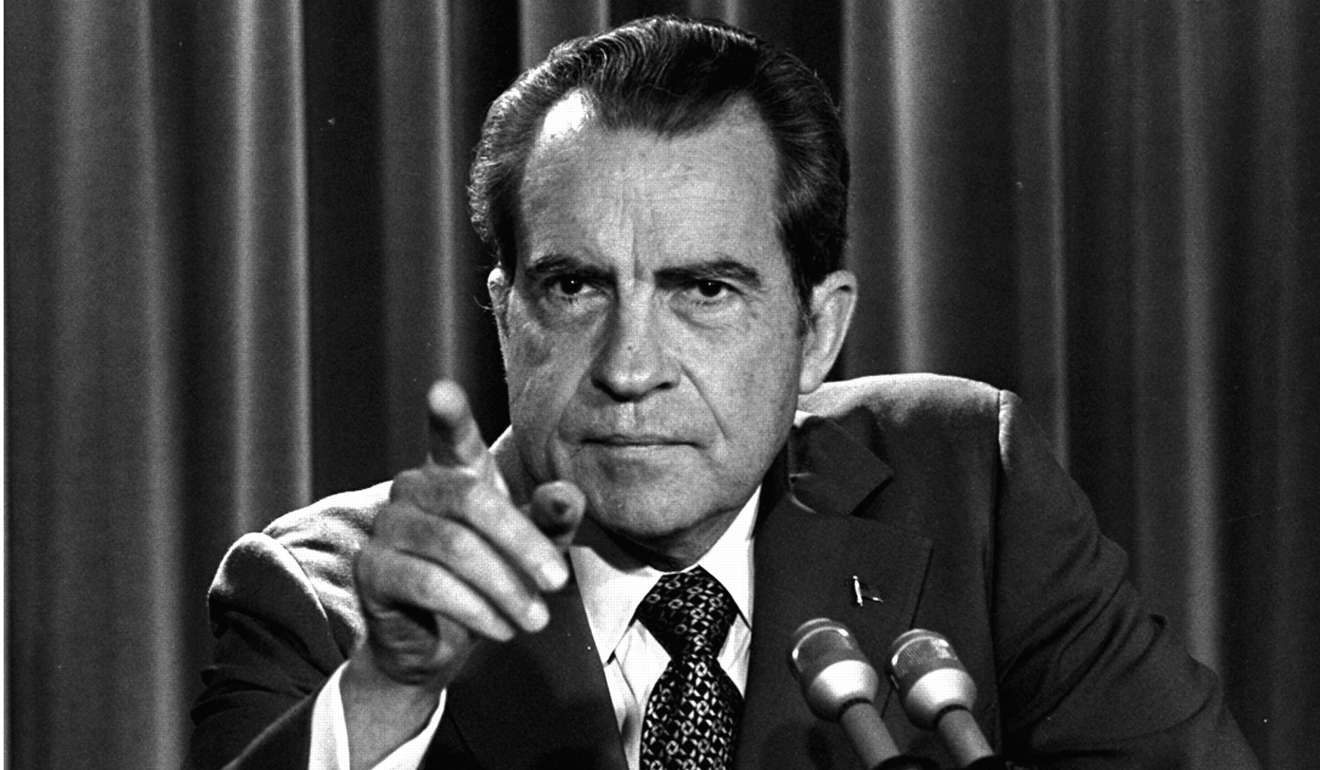

These are among the many, many things journalists like to say are “unprecedented” about the administration of President Donald Trump. Yet all the things I have just written could equally well have been written about Richard Nixon’s administration.

In 1969, The Washington Post reported that Nixon’s inaugural crowd was “far smaller and at times less enthusiastic than the 1.2m” that had turned out for Lyndon Johnson in 1965. Nixon scrawled in the margins of his news report the next day: “The press is the enemy.” Sound familiar?

Early in his first 100 days, Nixon also picked a fight with a show that made fun of him, the Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour. And his press secretary, Ron Ziegler, was despised by Washington journalists.

After his first news conference, Nixon sent a memo demanding, “on an urgent basis”, a list of those in the White House press corps who were against him. In future, he said, he would call only on his friends and not those “who are definitely out to get us”. It was his fury over leaks to the press that led to the wiretapping of National Security Council staff, just as Lyndon Johnson had once bugged him.

For Smothers Brothers read Saturday Night Live; for Ron Ziegler read Sean Spicer. So closely is Trump following the Nixon script that, for the first time, I begin to fear for his future.

True, with the benefit of hindsight, we tend to think that Nixon was always doomed to self-destruction. In reality, in 1969 the Watergate scandal was still a long way off. The fateful attempt to bug the offices of the Democratic National Committee was made on June 17, 1972. Five months later, Nixon achieved one of the biggest landslides in American history.

No one has boosted sales of the ‘failing’ New York Times the way Trump has

As Trump’s administration digs itself into ever-deeper holes over his campaign’s contacts with the Russians, he needs to remember the lessons of Watergate. No 1: declaring war on the press is a high-risk strategy because it has the biggest possible incentive to get you. No one has boosted sales of the “failing” New York Times the way Trump has. No 2: it’s the cover-up that kills you.

Yet there is one big difference between then and now. Trump has an advantage that Nixon never had, not even after his 1972 triumph: the Republican Party has a majority in both houses of Congress.

I spent the early part of last week on the Hill. At dinner on Monday, I sat opposite the House Republican leader. I called on the chairman of the House Intelligence Committee. I attended a lunch addressed by the Speaker of the House. I even took a late-night tour of the chamber where the House of Representatives meets and stood where the president stood last Tuesday night, when he addressed a joint session of Congress, watched not only by the television cameras but also by the bas-relief faces of history’s great lawmakers. This is what I learnt.

After five weeks when the headlines were dominated by executive orders, nominations and tweets emanating from the White House, the action has now shifted to the Hill. Commentators remarked on the more conciliatory tone of the president’s speech. I was more interested in the content. In essence, it set out the legislative agenda of the House Republican leadership.

Those who warned of a Trump tyranny have been wrong so far. Rather, the president looks more like an unruly constitutional monarch – a king on a fixed-term contract – who loses court battles, picks fights with the press, gives speeches and leaves the legislating to Paul Ryan and his colleagues.

Ryan [and] McCarthy are indefatigably energetic. And they know what they want to do.

In British terms, Ryan is not the Speaker of the House; he is the prime minister, with House Republican leader Kevin McCarthy as a formidable chief whip. These men have long impressed me. They are young – Ryan is 47, McCarthy 52. They are indefatigably energetic. And they know what they want to do.

In essence, the House Republicans have a 200-day plan. The programme is as follows. First, regulatory reform, including repeal of the Dodd-Frank banking act and deregulation of the energy sector. Second, the repeal of Obamacare and its replacement with a more competitive market-based system. Third, comprehensive tax reform, including lower rates on personal and corporate income tax, a new border adjustment tax (BAT) and abolition of the inheritance tax.

Ryan & Co see this programme of radical reform as theirs. And they see this year as a historic opportunity – “one of those moments that never comes back again” – to take advantage of unified Republican government across the White House, House and Senate.

What are the obstacles? The most obvious is the slow progress of the White House in staffing the administration, creating a backlog of confirmation hearings in the Senate.

Second is the complete evaporation of any possibility of bipartisanship, as the defeated Democrats, led by Senator Chuck Schumer, respond to pressure from the more radical elements of their voter base. Not everything can be filibustered to death in the Senate, but a lot can.

Third is the resistance to BAT (which is, put simply, a value added tax on imported goods) from lobbyists and corporate interests. So effective has this resistance been that I heard it described more than once as “DOA” – dead on arrival.

However, the most striking opposition I heard the House leadership refer to was the “conservative-industrial complex” of talk radio, right-wing websites and the remnants of the Tea Party. It is not only the left that enjoys demonising Ryan these days.

My favourite number in the musical Hamilton is The Room Where It Happens, which describes the famous compromise reached between Alexander Hamilton and James Madison over dinner in 1790. The federal government took over the states’ debts (as the Treasury secretary from New York wanted) but the national capital was moved to the South (as the congressman from Virginia wanted). The House is now the room where it happens.

As the song says: “No one really knows how the game is played / The art of the trade / How the sausage gets made.” But the Hamilton-Madison deal is why so much of American politics takes place in the District of Columbia, formerly a swamp on the Virginia-Maryland border. Trump is not the first president to have spoken of draining that swamp. If, by treading unwarily, he sinks in it, he will not be the last to do so.

Niall Ferguson is a senior fellow of the Hoover Institution