Wang Qishan is reading about history’s decisive moments, and so should we

Niall Ferguson says the book recommendation by China’s powerful anti-corruption chief to his Politburo Standing Committee colleagues will resonate as the hour of reckoning approaches on the Korean missile crisis

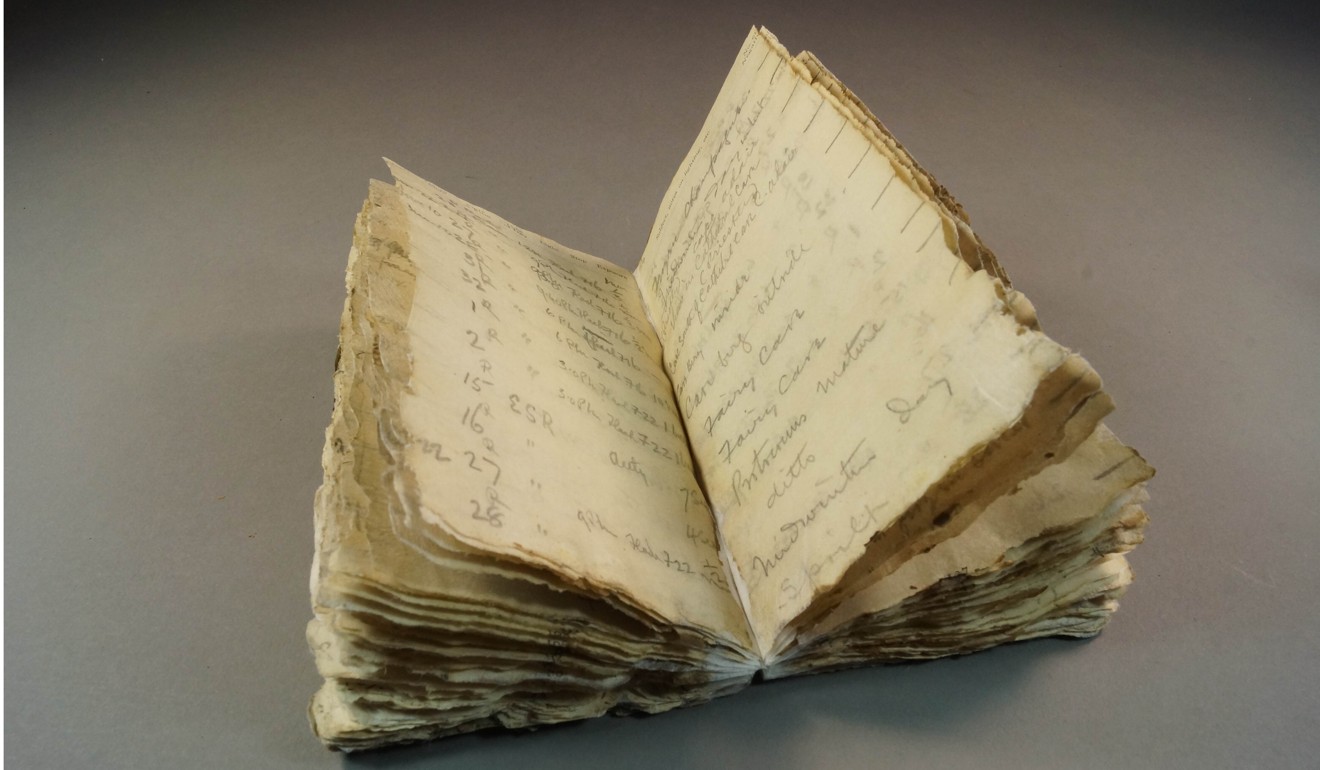

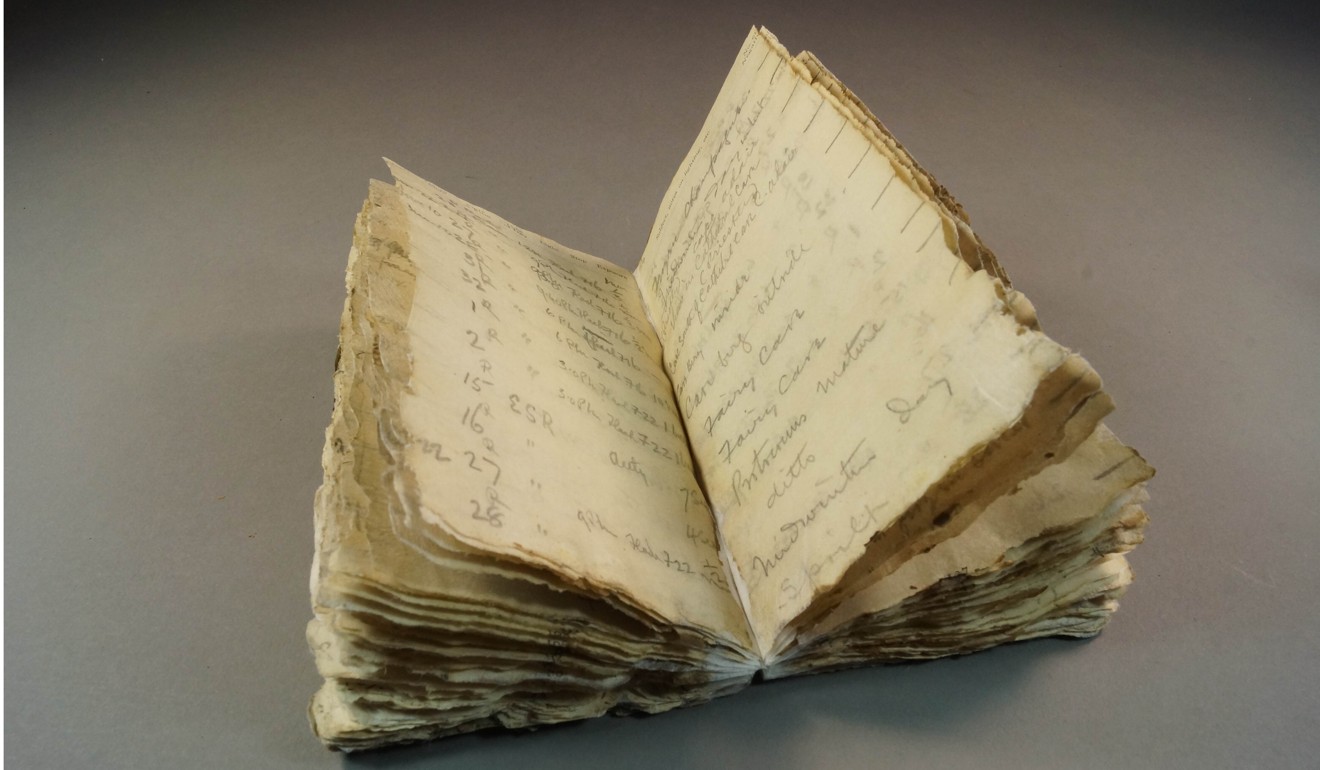

If you are stuck for a book to read this August, I recommend Stefan Zweig’s Decisive Moments in History. Published in 1927, Zweig’s book is now largely forgotten. My interest was piqued when a friend in Beijing told me it was the latest Western book to be recommended by Wang Qishan (王岐山) to his colleagues on the Politburo Standing Committee. (A few years ago it was Alexis de Tocqueville’s The Ancien Regime and the Revolution; more recently John Hirst’s The Shortest History of Europe.)

It pays to know what Wang is reading. As the head of the Communist Party’s anti-corruption commission, he is seen as the second most powerful man in China after President Xi Jinping (習近平). As we approach what may be the next decisive moment in history, we too should probably know what to look out for.

Usually, wrote Zweig, history does nothing but “add link to link in that enormous chain that stretches through the millennia”. Very occasionally, however, “a critical moment occurs in the world” that is “decisive for decades and centuries ... a single moment that determines and decides everything: a single yes, a single no, a too early or a too late makes that hour irrevocable for a hundred generations”. Zweig, a Viennese, called such moments sternstunden, best translated as “stellar moments”.

Part of the charm of Decisive Moments in History is the idiosyncrasy of Zweig’s selection. Three are famous events in political history: the fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans in 1453, Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo in 1815, and Lenin’s return to Russia in 1917. Others are less obvious but still significant in the history of exploration and economics: Balboa’s first glimpse of the Pacific Ocean, John Sutter’s discovery of gold in California and the fatal race between Scott and Amundsen to reach the South Pole.

You do not have to be a nice guy to change history

Yet it is to the first three turning points that the reader returns. The fall of Constantinople, in Zweig’s telling, is mainly the triumph of ruthless calculation by the young Ottoman sultan, Mehmed the Conqueror – but the fatal breach in the city’s defences is the result of a humble gate, the Kerkoporta, inadvertently left ajar.

Napoleon’s final defeat is the result of a fatal hesitation by Marshal Grouchy, who sticks to his orders to pursue the Prussian III Corps instead of riding to Waterloo when loud cannon fire heralds the battle’s decisive moment. “For one second Grouchy considers it, and this one second determines his own fate, that of Napoleon and that of the world.”

Lenin’s return to Russia is the result of an even bigger miscalculation: the belief of the German high command that the Bolshevik revolution will disrupt only the tsar’s empire, whereas by November 1918 Germany too is in the grip of workers’ and soldiers’ councils.

The question of the summer is whether the Korean missile crisis will be President Donald Trump’s sternstunde. The conventional wisdom is that his rhetoric last week – the threat of “fire and fury”, the warning that “military solutions are now fully in place, locked and loaded”– was yet more evidence of his recklessness. Perhaps. But Trump is not handling this crisis much differently from the way John F. Kennedy handled the Cuban missile crisis.

Watch: President Donald Trump escalates his threats against North Korea’s nuclear push

This crisis is the result of three previous presidents’ inability to stop the tinpot totalitarians of Pyongyang acquiring fissile material and missiles.

It is hard to have any confidence in a president so impetuous, so undisciplined

Confronting Kim is risky, but not as risky as confronting Khrushchev and Castro in 1962, when a third world war really was a possibility. Moreover, unlike in 1950, I believe China will not intervene if the US takes military action against North Korea, provided the US does not attempt regime change and reunification of Korea.

It is hard to have any confidence in a president so impetuous, so undisciplined. Yet, as Zweig understood, you do not have to be a nice guy to change history. Indeed, sensible types tend to be the ones (like Grouchy) who miss their historic moments.

No one knows how this will turn out: stellar moment or epic fail. Socio-economic forces will not tell you. And that is why, these days, China’s leaders are reading not Karl Marx but Stefan Zweig.

Niall Ferguson is a senior fellow of the Hoover Institution, Stanford