The mixed fortunes of Eurasians: how Hong Kong, China and US viewed intermarriage

In her book Eurasians, MIT professor contrasts attitudes towards interracial marriage in three jurisdictions, and how mixed-race families in Hong Kong were able to grow wealthy despite facing discrimination

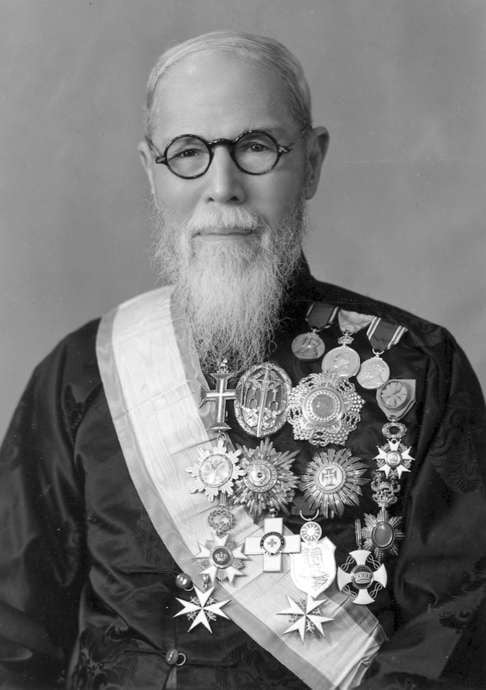

Interestingly, although influential Eurasian businessman Sir Robert Hotung was one of the key founders of Chiu Yuen – he and several family members went to London to petition for a Eurasian burial ground in Hong Kong – he wasn’t buried there. Instead, Sir Robert – the first person with

Chinese blood allowed to live on The Peak – was interred at the Colonial Cemetery in Happy Valley, now known as Hong Kong Cemetery, alongside his first wife. But all of his other direct family members, including his second wife, were buried at the Eurasian cemetery.

Teng was in Hong Kong this month to give talks at The Helena May and the Asia Society – based on research for her 2013 book, Eurasian: Mixed Identities in the United States, China and Hong Kong, 1842-1943.

The most striking differences in the experiences of Eurasians in the three jurisdictions stemmed from the law, she says. At that time, the US had racist anti-miscegenation laws – a legacy of the days of slavery – and while most of the laws were in place to prohibit black intermarriage, individual states gradually began to pass laws banning Chinese intermarriage, too. It varied from state to state, and about 15 states passed laws that prevented Americans and Chinese from marrying.

But the picture was very different in Hong Kong.

In mainland China, the situation was different still. Although at various points in history China had laws preventing Han Chinese from marrying Manchu people, because of inter-ethnic conflict, there were no laws against Chinese and Westerners tying the knot. However, there was one exception, introduced in 1910 – Chinese students studying overseas couldn’t marry foreign women.

“The students were supposed to go abroad and get a modern education, and come back and help China modernise,” Teng says. “And there was a fear that if they married a foreign woman, she might induce him to stay abroad.”

Interestingly, when China introduced its first nationality law, in 1909, it defined Chinese citizenship as being derived through the paternal bloodline – if your father was Chinese, then you were also Chinese, regardless of where you were born.

Basing much of her research on old memoirs, Teng says it was evident that prejudice towards Eurasians waxed and waned depending on the degree of tension between the US and China.

In the US, the Chinese Exclusion Act – passed in 1882 for a 10-year period and made permanent in 1904 – prohibited the immigration of Chinese labourers. It was the first law implemented to prevent a specific ethnic group from immigrating to the US, and it wasn’t repealed until 1943.

“Around the time when it was passed, you see [in memoirs] a lot of anti-Chinese sentiment rising up again,” Teng says.

In China, Eurasian families were caught up in the surge of violent, anti-foreigner sentiment that sprung from the Boxer rebellion, from 1899 to 1901. The lead-up to the Chinese revolution of 1911 was also a very difficult time for Eurasians.

“There was a big movement of Chinese racial nationalism and purity – the idea of China for the Chinese, and to get rid of all of the outsiders. At that time you could also see quite a lot of xenophobic reactions,” Teng says.

But it wasn’t all bad news for Eurasians in mainland China. It was probably the easiest – or least difficult – place to be Eurasian, for the most part. Most Eurasians in China lived in small enclaves, and many were the children of elite Chinese males, such as diplomats, who had married abroad and brought their wives back. They were living in very cosmopolitan pockets of Shanghai and Beijing.

Eurasians in Hong Kong had a harder time, Teng says, “because they weren’t accepted by the British, and they weren’t really fully accepted by the Chinese either, so they developed their own community where there was very heavy rates of intermarriage among the Eurasians families”.

Despite the challenges for Eurasians in Hong Kong, there were also opportunities. Many became compradores, able to bridge East and West and facilitate British trade with China.

“Several of them became quite rich in the process,” including the family of Robert Hotung, who had a Chinese mother and a father with Jewish-Dutch roots. “The compradore position would often be passed on through their families ... to a son, uncle or nephew, and with the heavy intermarriage within these families you had a consolidation of power and wealth that could offset, in some respects, the prejudice from others,” Teng says.

Teng, a US citizen, says she has also faced prejudice, recalling once being told to, “Go back home to your own country”. But a turning point came in the 1990s, she says. The change can be traced back to the post-war period with the renunciation of Nazism and its extreme racial ideologies, which led to a series of legal reforms. One defining case was in 1967 when, as part of the broader civil rights movement of the 1960s, the US Supreme Court removed the last of the anti-miscegenation laws. What followed was a biracial baby boom, and many of those children born in 1969 and 1970 began college in 1990.

“College is a very important time for young people to discover and talk about their identity. This multiracial movement that gained a lot of power in the 1990s managed to get the US Census to change its way of accounting for race,” Teng says.

Rather than having to tick just one box, the US Census of 2000 allowed people to tick as many boxes as they identified with. And a year later, Britain also changed its census to allow people to indicate whether they were of mixed heritage.

“Many descendants, even here in Hong Kong, are publishing memoirs or histories of their families comprising genealogy, really trying to revive this history,” Teng says.