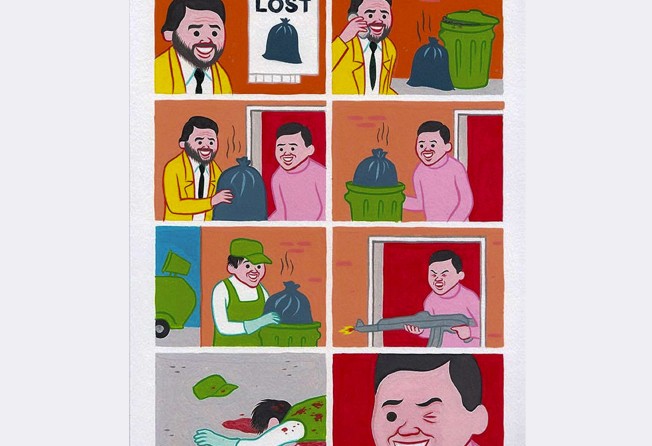

Tales of murder, casual violence and infanticide that Hongkongers love

Spanish cartoonist Joan Cornella draws on the darkest parts of human nature in his comic strips and a lot of his fans are from Hong Kong

There is, apparently, something quite dark in the humorous tastes of Hongkongers.

“Most of my followers on Facebook are from Brazil and Hong Kong,” says Spanish cartoonist and illustrator Joan Cornellà – who has more than three million followers, and whose work is very dark indeed.

Cornellà sets up a brilliantly awkward tension between form and content, with his disquieting themes rendered using brightly coloured, simply drawn, ever-smiling, childlike people: cartoon emblems of empty cheeriness, like 1950s US advertising or airline safety cards.

You’re led to expect the usual redemptive narrative, only for the whole thing to get turned on its head in a way that is simultaneously quite upsetting and deeply hilarious.

So, for example, a woman slices herself in half so her two halves can hold hands, in a comically excessive overreaction to the widely stigmatised state of singleness; a man burned in a petrol fire gets adopted by a white couple as their token black baby; a man is caught watching porn by his wife, who objects until she changes it to animal porn; a man consoles a small girl who’s lost a balloon by stealing a syringe from a homeless drug user and injecting her; and the highest member of a human pyramid of cheerleaders is gradually revealed to have a noose around her neck.

On the other hand, someone somewhere in the social media echo chamber is going to get offended by everything, and Cornellà gives the perpetually offended plenty of material to work with. The internet can be a double-edged sword, he says, but adds that problems mainly result from its commercialisation.

“Social networks have helped me to have a gigantic broadcast channel that I could not have had otherwise,” says Cornellà.

“At first I started doing mute cartoons to experiment, but as I published them on Facebook I quickly realised that if they were silent I could reach out to more people. It was not a decision I made deliberately but by continuously trying different things I was outlining the style my comics have today.

“When they started to go viral I received a lot of negative feedback, with people writing angry complaints and insults. Now these people just report my work to the networks, and because of that I get blocked by Facebook constantly.

“The internet should be a space of freedom where different views can be espoused, but the problem is the internet is dominated by companies like Facebook that dictate absurd rules.”

Cornellà’s cartoons cross cultural boundaries so easily because of their absence of words, but that hasn’t always been the case. He started out drawing cartoons with lots of text, which was where most of the humour was located.

“One day I started doing mute comics and I liked it,” he says. “Before then I’d thought it was much more difficult. As I progressed doing silent stories I realised it was a way to reach to a wider audience, not limited to those who spoke my language.

But Cornellà adds that he prefers to step aside from the different readings made of his cartoons: “I like that there are such different interpretations of the same story. Sometimes people bring out philosophical discourses that I do not understand or see intricate, complex social criticism in them.

“I do not know: I leave it for people to draw their own conclusions. I can have a concise idea of what I mean sometimes, but most times I prefer my work to be open and ambivalent.”

His work invariably shows people at their worst; in particular, anyone who appears to be helping someone else almost always turns out to be doing precisely the opposite.

“I agree with a phrase by Bill Hicks: ‘I believe there is an equality to all humanity. We all suck.’ In my comics characters are like plastic and always have a big smile even though horrible things happen to them constantly. Everything is exaggerated, although certain behaviours can relate to real life,” he says.

“We must start from the idea that when we laugh, we laugh at someone or something. With empathy or not, there is always some degree of cruelty. In spite of that, I am aware that if one of my cartoons happened in real life I would not laugh at all.

“For me personally, it is fiction that allows me to laugh. Reality is quite creepy.”

As well as selling his work as one-off art pieces, Cornellà has also published a series of books, most recently last year’s Zonzo.

Similarly, he faces the challenge of trying to sell two versions of the same thing to very different groups of people, ones who buy original art works and ones who buy books – while also giving most of his work away free.

“I started doing comics to escape the world of art and its pretentiousness,” Cornellà says. “It was not my intention that my work to be considered art but right now there are people who do see it in this way.

“There are two modes of consumption of my work: some see it like anything else one can find on the internet, as a meme or as fun trash, and some see it as a work of art. Anyone can choose: I do not care.”

The cartoonist says those who buy his work constitute a very small group, despite having more than three million followers on Facebook: “Let’s say that my work reaches many people for free and that thanks to it some of those people pay me.”

“Joan Cornellà”, Connecting Space Hong Kong, G/F, Wah Kin Mansion, 18-20 Fort Street, North Point. June 17 to 26, 10am-10pm. Admission: HK$50.