Why notoriously insular and protective Nintendo let Mario appear on iPhones

Spurred by slow console sales and the unexpected success of Pokemon Go, Nintendo creator Shigeru Miyamoto has finally let his iconic creation appear on non-Nintendo platforms

Shigeru Miyamoto is hoping that Pokemon Go’s summer magic will rub off on his fabled Nintendo gaming character Mario.

“The Pokemon Go phenomenon shows the power of the smartphone,” says Miyamoto.

Game developers Niantic created the raging hit in partnership with Pokemon creators Nintendo. “Before the summer, there were questions about Pokemon’s popularity. Now, millions are playing,”

Miyamoto said, shortly after announcing that Mario would be coming to Apple’s App Store (iPhone and iPad) in December (it's also heading to Android at some point).

Also announced was that Pokemon Go would be coming to the Apple Watch.

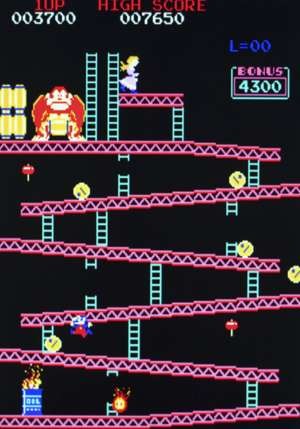

The 63-year-old’s road to fame started in 1981 with the creation of Nintendo’s first big arcade hit, Donkey Kong. The game designer later added a moustachioed Italian character to the mix named after a warehouse landlord. Soon Mario, his brother Luigi and their antics were powering the home console and hand-held gaming device trend of the 1980s and ’90s.

According to Miyamoto, the iPhone version of Mario’s latest gaming adventure, called Super Mario Run, has been a year in the making. The delay in bringing the jumping character – originally called Jumpman – to a smartphone was “because up until recently we found that mobile devices weren’t best suited to gaming. But that’s changing.”

It can’t be overstated how unusual it is for Nintendo to bring its main mascot to hardware made by a company that isn’t Nintendo. This is not something that happens and it’s a big deal for the company, according to game industry analysts.

Nintendo has fiercely guarded its properties for as long as those properties have existed. A few notable exceptions can be found in the Super Mario Bros movie, Hotel Mario, and a few other odds and ends, but Nintendo tends not to act casual about its properties.

Nintendo was notoriously slow to acknowledge this trend.

The Japanese game company has made plain over and over that a move to mobile could mean the devaluing of its extremely valuable intellectual properties: Super Mario, The Legend of Zelda, Donkey Kong, and other gaming classics. Nintendo is basically the Disney of video games.

“In the digital world, content has the tendency to lose value, and especially on smart devices, we recognise that it is challenging to maintain the value of our content,” late Nintendo president Satoru Iwata told Time magazine in 2015. “It is because of this recognition that we have maintained our careful stance.”

But this stance has now been softened. That’s partly due to sluggish game console sales, Nintendo posted a group net loss for the April to June quarter, falling into the red for the first time in two years.

Nintendo isn’t “late” to the mobile game market as much as it has tried to ignore the world of mobile gaming for the past decade. Which is why Nintendo’s move to mobile is so huge. It’s no surprise that Nintendo's stock shot up by nearly 30 per cent in wake of the September 7 announcement.

Asked if he was bringing Mario to the newest gaming platform, virtual reality, Miyamoto says that VR wasn’t quite the right fit.

“I would agree that adapting Mario to new platforms is a key to keeping him relevant,” he says. “But we want families to play together, and virtual reality [which requires players to be closed off from the real world] doesn’t really fit well there. We also like people playing for a long time, and it’s hard to do that in VR.”

In a quick play of Super Mario Run, Mario ambles along collecting points and avoiding obstacles with the help of quick jumps provided by taps on the smartphone’s screen. In its simplicity, the game resembled Angry Birds, although the game designer promised that Mario would soon be able to make more complex movements.

Although Mario’s world may not be as layered as that of Star Wars, the character is perhaps globally as recognisable as C3PO and R2D2.

Miyamoto professes a deep admiration for series’ creator Lucas, noting that upon meeting him “I just turned into a fanboy right away. I love how he just took a dream of his, and turned them into those movies.”

If Miyamoto has a dream, it’s one you might not guess.

He’s a long-time devotee of bluegrass who particularly appreciates the sonic brilliance of mandolin player David Grisman and guitarist Tony Rice. Miyamoto plays guitar as often as he can with friends and would love to take his skills up a notch, though he admits being a bluegrass devotee in Japan has its limitations.

“In university, a few friends and I wanted to start a bluegrass band, but we had a hard time finding anyone who played banjo,” he says through an interpreter, nothing that the group would get requests to play parties and bakery openings.

“But it worked out OK. If you wanted bluegrass, well, we were the only band around.”