Book review: The Cultural Revolution on Trial – when China put Gang of Four in the dock and flirted with radical legal reform

As Xi Jinping resurrects the practices of Maoist China, such as intensifying party control over the judiciary, Alexander Cook’s book is a reminder of the moment party ducked a historic opportunity for de-Maoification

The Cultural Revolution on Trial

by Alexander Cook

Cambridge University Press

3 stars

China’s civil society has suffered badly in the political crackdown of the past four years: journalists are stifled by ever tightening constraints; intellectuals are nervous of even saying the president’s name in company, for fear of being seen as denigrating the cult of “Uncle Xi” .

Above all, the Chinese Communist party has rained down blows on the rule of law. Legal personnel have been held for months in “black” prisons without access to counsel and been shackled, tortured, their family members harassed. On January 14 this year, China’s chief justice aggressively emphasised that the law was subservient to party writ: “We should resolutely resist erroneous influence from the West: ‘constitutional democracy’, ‘separation of powers’ and ‘independence of the judiciary’. We must make clear our stand and dare to show the sword.”

Intensifying party control over the judiciary is part of Xi Jinping ’s resurrection of the values and practices of Maoist China. The roots of party domination over the law go back to the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, at which point the party began to empower itself – rather than an adversarial, independent judiciary – to define criminality, usually on the politicised grounds of “class identity”. Mao’s political campaigns – especially the Great Leap Forward (1958-60) and the Cultural Revolution (1966-76) – smashed legal institutions and marginalised legal professionals.

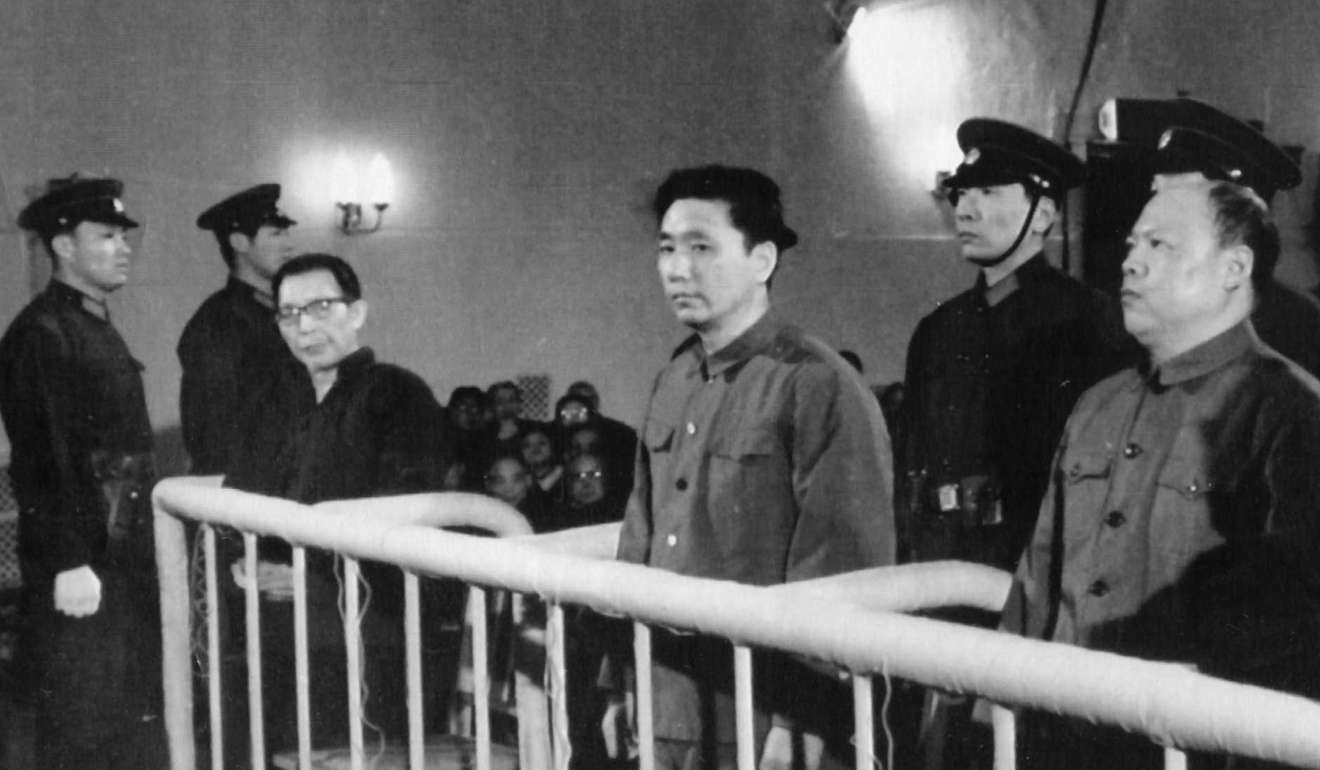

But in The Cultural Revolution on Trial, Alexander Cook chronicles an extraordinary potential turning point in the evolution of the law in the People’s Republic. The most sensational legal process in the history of communist China, the 1980 trial of the Gang of Four was designed to terminate the politics-in-command lawlessness of Mao’s Cultural Revolution, and usher in Deng Xiaoping’s vision of a modernised state devoted to rational economic construction. At this crux moment, China flirted with a drastic overhaul of its party-political legal system. Although the enterprise was ultimately stymied by political compulsions, it set a precedent for radical legal reform, and for possible de-Maoification.

During the last decade of Mao’s life, his words – or his words as interpreted by the ambitious political operators around him – carried supreme authority. “Depend on the rule of man,” he exhorted, “not the rule of law.” The vendettas of 1966-76 generated countless personal tragedies and injustices – individuals persecuted, imprisoned and killed for alleged political crimes.

When Deng – purged twice during the Cultural Revolution – manoeuvred himself into the party leadership in 1978, he was faced with a crisis of political and legal legitimacy. How was he to justify jettisoning Mao’s Cultural Revolution (the excesses of which had generated such widespread suffering) while asserting his and the party’s entitlement to rule as the heirs of Mao?

At the end of the 1970s, a fierce debate about de-Maoification took place in the upper levels of the party, dominated by individuals who had suffered during Mao’s purges. Deng eventually decided not to repudiate Mao – the Great Helmsman was too crucial to the prestige of the communist revolution. Although the Cultural Revolution was publicly labelled “the error of a great proletarian revolutionary”, Mao’s portrait and embalmed corpse would stay in Tiananmen Square; his Thought would remain one of the “four cardinal principles” of Communist Party rule.

Instead, Deng and his lieutenants reached for legal means to smooth the transition. They resolved to reconstruct China’s ruined legal system and stage a public trial that would blame the cataclysms of the preceding decade almost entirely on the Gang of Four, Mao’s closest allies during the Cultural Revolution: his wife, Jiang Qing, the two writers Zhang Chunqiao and Yao Wenyuan, and the labour activist Wang Hongwen.

The prosecution, Deng hoped, would shore up the domestic and international reputation of the new communist leadership by proving its commitment to a professional, rational, evidence-based legal culture, and ending the mob violence of the Mao era.

The undertaking, Cook relates, became a national spectacle. Courts had to be reopened, lawyers and judges rehabilitated, legal codes written for the first time. The address of the court building was edited so that the trial would take place at “No 1 Justice Road”; the interior of the chamber was upholstered in stately crimson velvet. Through the closing weeks of 1980, Chinese people gathered nightly around television sets to watch digested coverage of proceedings.

The trial did not succeed in creating a transparent, independent judiciary. The very premise of it was irrational: to blame four individuals for mass violence and persecution in which tens of millions participated. In the absence of an adversarial defence, the verdict was preordained: after four weeks of closed-door deliberation, the judges pronounced an inevitable guilty verdict.

This ruling, followed by a party resolution a few months later, officially closed the public debate on responsibility for the Cultural Revolution. Although hundreds of thousands of its victims were rehabilitated after Mao’s death, most of the crimes committed between 1966 and 1976 escaped prosecution.

Yet the trial’s red-velvet stage set exposed intriguing fault lines in a political system struggling to break with revolutionary politics. The best theatre came from Jiang Qing, a former actress, who loudly protested at the unfairness of criminalising her now when only four years previously her actions had been fully sanctioned by Mao, the unquestioned head of state. “Everything I did, Mao told me to do. I was his dog; what he said to bite, I bit.” She defiantly turned the accusations back on the judges, reminding them that they had persecuted victims of the purges as fervently as she had. “If I am guilty, how about you all?” Temporarily forgetting their brief to maintain legal decorum, the flustered judges chorused back at her: “Shut up, Jiang Qing! Shut up!”

There is still much we do not know about the shift from Mao to Deng. The details of this singularly sensitive transition – the arguments for and against de-Maoification – will only become public if the party itself falls from power. But the questions and dilemmas this process raised – the struggle to establish legal authority independent of a one-party dictatorship determined to suppress challenges from civil society, and to come to terms with the legacy of Mao and his revolution – still haunt China today.

The Cultural Revolution on Trial reminds us of the historical possibilities of legal reform and the long shadow of Maoism over Chinese law. It is a timely, thought-provoking account of a foundational episode in the history of contemporary China.