Book review: By More Than Providence is a brilliant history of America’s evolving grand strategy towards Asia-Pacific

Combining historical scholarship, an understanding of America’s strategic culture and shrewd geopolitical insight, Michael J. Green has written what is destined to become a definitive work

By More Than Providence: Grand Strategy and American Power in the Asia Pacific Since 1783

by Michael J. Green

Columbia University Press

4.5/5 stars

“Man cannot control the current of events,” remarked Otto von Bismarck, “he can only float with them and steer.” The great German chancellor understood that it is much easier to design a grand strategy for international politics than to implement one, something that is made crystal clear by Michael J. Green in By More Than Providence, a brilliant and highly readable history of America’s evolving grand strategy toward Asia and the Pacific since 1783.

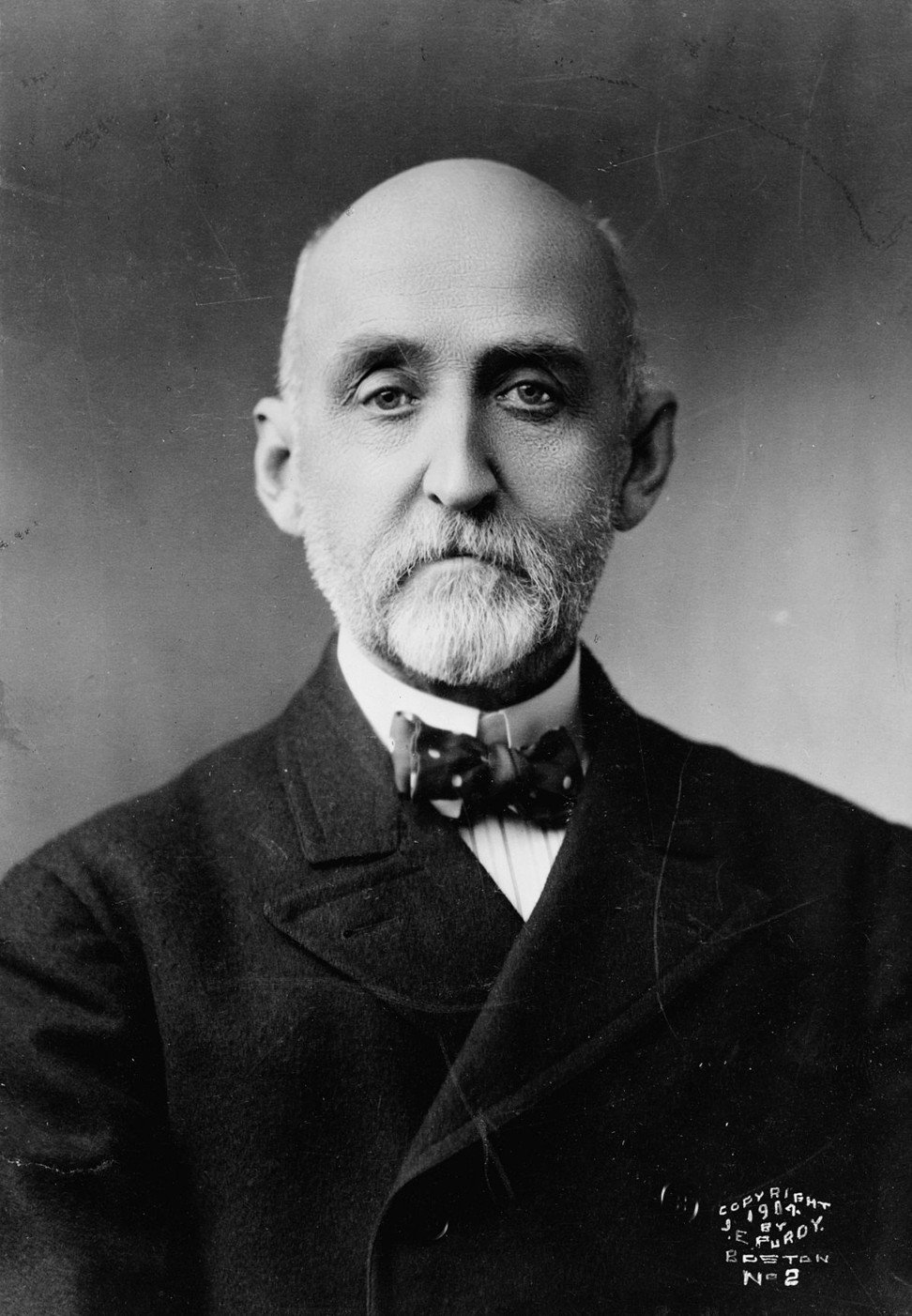

In the book, Green, a former US National Security Council staffer and currently an Asia scholar at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, combines historical scholarship, an understanding of America’s “strategic culture” and shrewd geopolitical insight informed by the timeless writings of Halford Mackinder, Nicholas Spykman and Alfred Thayer Mahan. The result is a tour de force that is destined to be the definitive work on the history of America’s strategic approach to the Asia-Pacific region for many years to come.

Green explores what he calls the “five tensions” that reappear throughout history in America’s approach to Asia-Pacific: Europe versus Asia; continental versus maritime; defining a forward defensive line in the region; self-determination versus universal values; and protectionism versus free trade. Between these, he writes, US statesmen have “struggled to find the right balance”.

Contrary to conventional wisdom in America that Asia attracted US strategic attention only after the Spanish-American War, the United States has in fact interacted with Asia and the Pacific since the early days of the republic, beginning with commercial and missionary activities that set the stage for exploration and, ultimately, political expansion.

Green recounts the growth of US naval power in the 1820s and 1830s, the exploration of Pacific islands in the late 1830s and 1840s, President John Tyler’s extension of the Monroe Doctrine to Hawaii (then called the Sandwich Islands), Secretary of State William Seward’s strategic vision of acquiring islands to form “stepping stones across the Pacific”, and Admiral Matthew Perry’s opening of Japan to American interests.

Grand strategy, however, requires both a grand strategist and political leaders to implement it. The United States was fortunate in the late 19th to early 20th century to have both.

Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan was a reluctant seaman but a brilliant writer and thinker who, Green writes, authored “the first comprehensive grand strategic concept for the United States in the Pacific”. In his book The Problem of Asia, Mahan “identified permanent American interests in key geographic areas of the globe in terms of geography, spatial factors and the distribution of power”. Central Eurasia was the “debatable and debated land”, potentially dominated by Russia, with a weak but potentially powerful China and a rising offshore power in Japan.

Mahan wrote that the United States, with its new Asian and Pacific possessions acquired during and after the Spanish-American War, needed a strong navy to influence the balance of power in East Asia and the Pacific.

Theodore Roosevelt was an admirer of Mahan’s writings and frequently corresponded with him on international and naval subjects. As president of the United States, Roosevelt translated some of Mahan’s concepts “into effective national policy”. Roosevelt expanded US naval power and used diplomacy to maintain an Asian balance of power between Russia and Japan.

The next two decades, however, witnessed a shift in priorities from Asia to Europe with the outbreak of the first world war. The two real “winners” of that war were the United States and Japan, whose interests began to collide in the Pacific and East Asia. Roosevelt and Mahan foresaw this, but Woodrow Wilson and his immediate successors placed their trust not in an American-influenced balance of power but in treaties, the League of Nations and utopian arms-control agreements.

Green notes that although Franklin D. Roosevelt admired both cousin Theodore and Mahan, his approach to Asia throughout much of the 1930s was little more than “strategic drift”. After Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbour, FDR pursued a “Europe first” strategy that consigned Asia and the Pacific to secondary importance, much to the chagrin of America’s admirals and General Douglas MacArthur.

During the second world war, Mackinder and Spykman presciently warned that Russia and/or China could replace Germany-Japan as the next potential hegemon of Eurasia, and urged the democratic sea powers to pursue strategies to prevent or offset such a development.

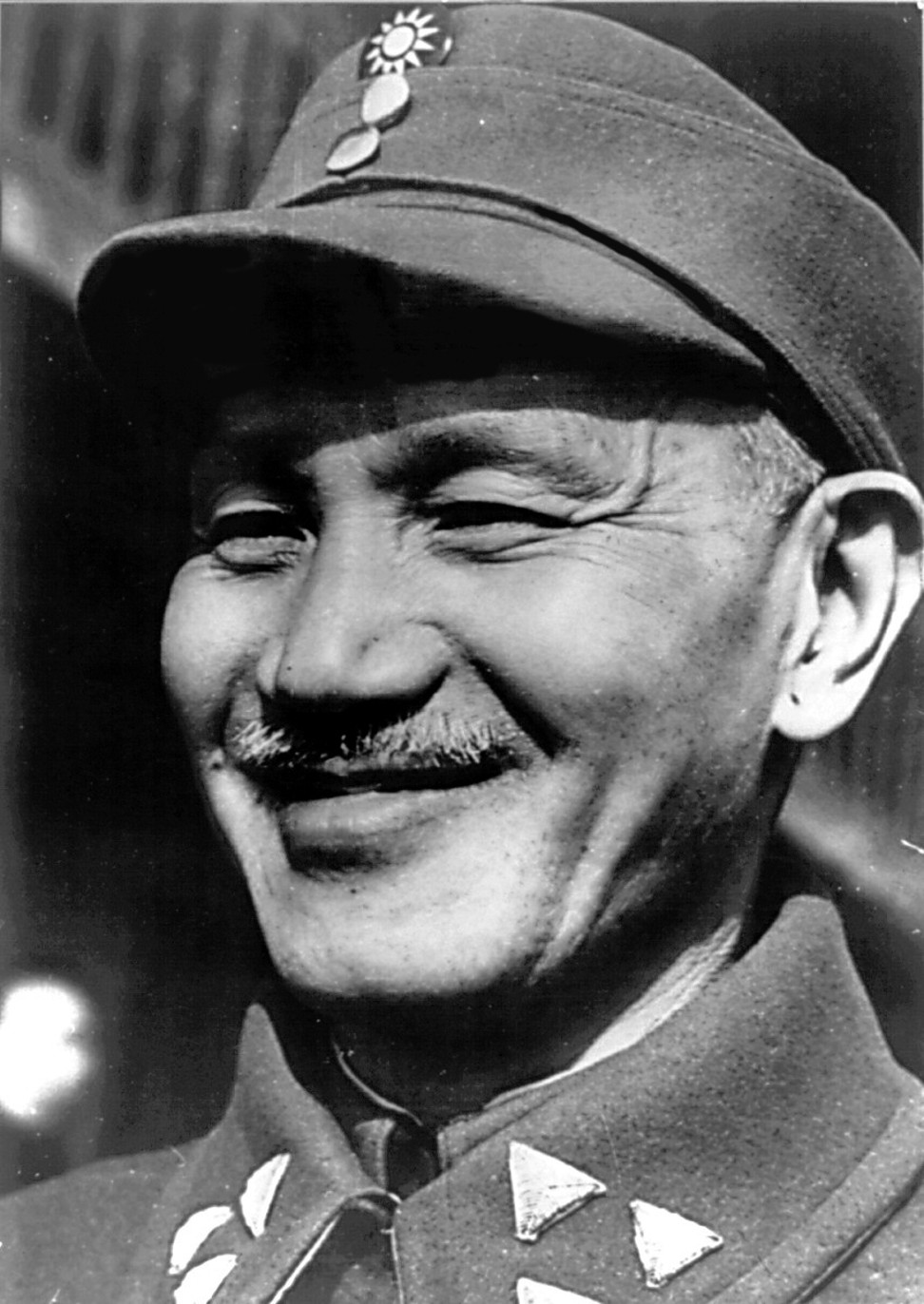

The emerging cold war in the late 1940s confirmed the wisdom of the geopoliticians. Green is scathing in his criticism of US policy toward China during the struggle between Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists and Mao’s Communists.

Had the outcome of the Chinese civil war been a divided China, Chiang’s forces would have served as a buffer against communist support for North Korea and later Vietnam. Arguably, the United States committed hundreds of thousands of troops to Korea and Vietnam and lost tens of thousands of men because it was unwilling to commit a few thousand advisors and a few hundred million dollars in additional aid to Chiang in 1947.

The “wise men” of the Truman administration fell far short of wisdom in their postwar approach to China, and the cost would be borne by US soldiers, sailors and airmen in two East Asian wars that resulted in stalemate and defeat.

Green is critical of the strategy (or lack thereof) employed by the Kennedy and Johnson administrations in Vietnam. However, he sides with Michael Lind and other revisionists, including Singapore’s late prime minister Lee Kuan Yew, in believing that the US effort in Vietnam bought time for the other nations of Southeast Asia, including Indonesia, to “fortify their political, economic and military capabilities” to effectively resist communist takeovers.

As the war in Vietnam sapped US willpower, President Richard Nixon (who Green rates second only to Theodore Roosevelt as a presidential geopolitical strategist) “took decisive steps to restore a favourable balance of power while realigning American ends with reduced American means”.

Nixon instituted “Vietnamisation” to extract US ground troops from Southeast Asia, applied the concept to other areas as the so-called “Nixon Doctrine”, pursued hard-headed detente with the Soviet Union, and orchestrated the opening to China – which Green believes, with Henry Kissinger, set the stage for the Reagan administration’s policies that ended the cold war on favourable terms for the US.

Green laments that no American president since Reagan has rooted the country’s Asia-Pacific strategy in “a clear understanding of the geopolitics of the region”. Most recently, the Obama “pivot” to Asia, he writes, has been more rhetoric than reality as US defence budgets declined and America became preoccupied with Eastern Europe and the Middle East.

As China rises economically and militarily, US statesmen, Green writes, must understand that America “emerged as the pre-eminent power in the Pacific not by providence alone but through effective … application of military, economic and ideational tools of national power to the problems of Asia”.

Asian Review of Books