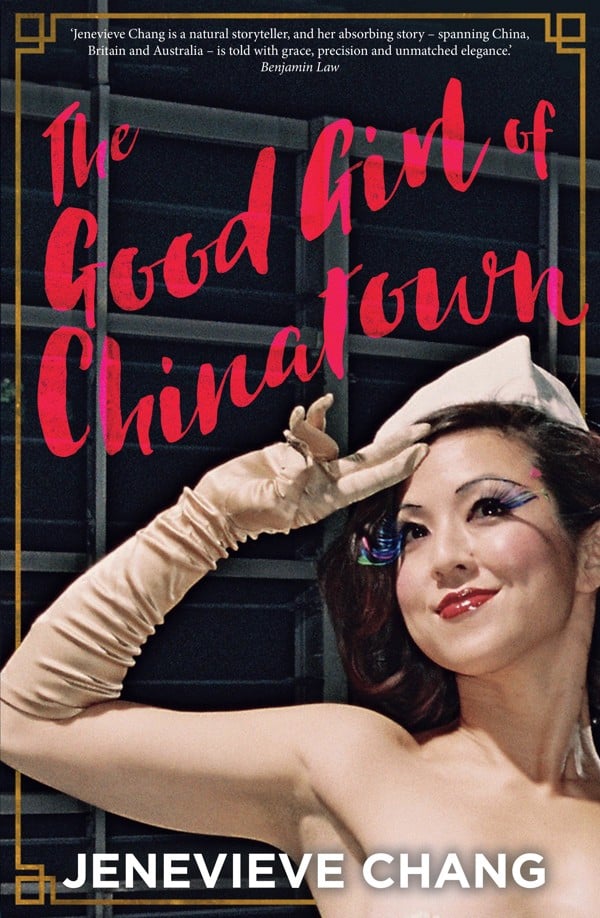

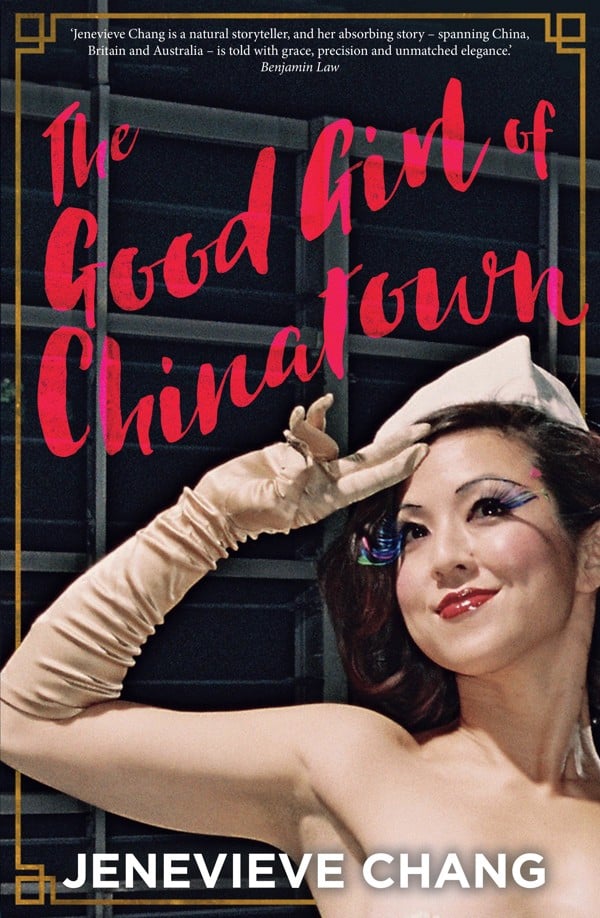

Burlesque dancing in China: Jenevieve Chang on expat parties, performing for Jackie Chan and reconnecting with her violent dad

The author of new book The Good Girl of Chinatown reveals her glamorous life as a Shanghai burlesque dancer and how an obedient Chinese-Australian daughter was drawn to the extravagant dance form

“Filth” is an acronym familiar mostly to expatriates: failed in London, try Hong Kong. “You can apply that to Shanghai as well,” says Jenevieve Chang, who spent several years in the Chinese metropolis in the late noughties. “They come to China and are suddenly superstars by virtue of being foreign.”

In her time in Shanghai’s expatriate playground, Chang, who worked there as a burlesque dancer, met film producers who had criminal records in their home countries and out-of-work Australian actors who landed starring roles in Chinese soap operas. Having a white face afforded you cultural capital: foreigners “were automatically offered four times a working wage than a Chinese-looking person”, she says.

When she was asked to fill in for a dancer for a performance in the northeastern city of Yantai, for instance, the nightclub owners were livid that she was Asian – and refused to pay her.

Chang’s experiences of Shanghai feature in her first book, The Good Girl of Chinatown, which chronicles her time as a dancer in the eponymous burlesque club. The decadent club opened to local fanfare and international media coverage. The proprietor’s vision, Chang says, was to “appeal to this idea of Shanghai once being the ‘whore of the Orient’, where anything could happen, where East meets West”.

Burlesque is a dance that is less about sensing the movement from within than interacting with the expectation of the gaze

Chang’s life in Shanghai was glamorous. She performed for the likes of Quincy Jones and an uncomfortable Jackie Chan, went to many an expat party, and inherited a designer wardrobe of Hermès, Prada and Vivienne Westwood from the late CEO of “a hotspot for Shanghai’s most prolific Eurotrash”. The success of Chinatown, however, was short-lived, marred by debts and run-ins with government officials over modesty.

In the book, Chang writes of the dance form: “Burlesque is a dance that is less about sensing the movement from within than interacting with the expectation of the gaze.” She compares it to the ad-libbing of standup comedians: “One has to sense the energy of the room, then enter into a dialogue with the audience.”

Liberation of the body drew Chang to burlesque. “That was really appealing after quite a repressive childhood,” she says.

Born in Taiwan, Chang had a peripatetic early upbringing, moving to the United States – first to Alaska, where her father was completing a master’s degree, and then to Utah – before growing up in suburban Sydney. She writes of being raised to be a stereotypically obedient Asian daughter, by parents who “were heavy-handed advocates of good behaviour, hard work, excellent grades and low social profiles”.

They emphasised their heritage, made their children go to Chinese school and speak Chinese at home. But this was at odds with the pressure to fit in with the rest of Chang’s classmates, which is common for young immigrants. Chang anglicised her Chinese name to Jen on the suggestion of a kindergarten teacher – an early indication of the life of reinvention that lay ahead.

In 2002, she moved to London after winning a place at the Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance. “I don’t think I was speaking to my father by then,” Chang says. Family fractures had begun to develop years earlier: her father was violent, and punishment for minor transgressions involved “a cane, a coat hanger or a slap across the face”. Chang also recounts her mother cutting up his suits after discovering he had given her chlamydia contracted from philandering.

The move to Shanghai was a second escape: she and her then husband were living in “a tough situation in London with three generations of his family”.

“It felt like I’d run away from one family to get trapped in another,” she says. China felt like the next frontier, abundant in opportunities for foreigners; it also spoke to a “sense of unfinished business” – her grandparents were forced to flee the country in 1949, when the Nationalist Party her grandfather fought for lost the civil war.

Chang believed the move to China, where she would be “part of the dominant culture”, would lead to a sense of belonging. Ironically, the China she moved to was “desperate to shed the shackles of its past and its isolationism, and desperate to embrace what was new and … foreign, anything that wasn’t Chinese”.

Previously, Chang never considered herself a writer. The memoir took her five years to finish. The book is written not only from her perspective, but takes imaginative licence in recounting her parents’ youth as well as that of her grandparents. Although her father hasn’t read the book, he was supportive of her writing it, she says. “It’s been a way that we’ve been able to bridge our conflict about the past.”