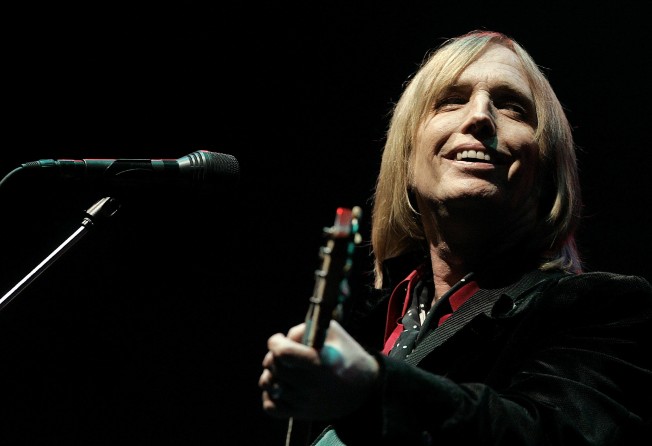

In final interview, Tom Petty talks about songwriting, touring and the holiness of the Heartbreakers

After finishing a marathon 40th anniversary tour, Petty speaks about learning to rest, how he’s almost never been sick and the excitement that comes writing and recording a new song. A few days later he died of a heart attack

This is not the Tom Petty story that I had intended to write.

Though I was more than thrilled to catch up with Petty, whom I had interviewed before, I had no clue that this would turn out to be the last, for me and for him – that he would die just a few days later on October 2 at the age of 66.

This is not the way things were supposed to happen.

It was a triumphant stand particularly rewarding to Petty, a Florida transplant who considered himself and his band mates California adoptees.

“This year has been a wonderful year for us,” he said. Above his head hung a framed illustration of his departed friend and boyhood idol George Harrison, created by artist Shepard Fairey and presented to Petty by Harrison’s son, musician Dhani Harrison. “This has been that big slap on the back we never got,” he said, referring to the popular, critical and financial affirmation that wasn’t always apparent throughout the group’s hard-working history.

But he did not see it as the end. There was supposed to have been so much more to come. Should have, would have, could have come.

After six rewarding but physical demanding months on (mostly) and off (hardly) the road, Petty was supposed to get a moment to relax and enjoy the return to domestic life with Dana, his wife of 16 years, and the rest of their family, including his two adult daughters, Adria and Annakim Violette, from his first marriage; Dana’s son, Dylan, from her previous marriage; and their four-year-old granddaughter, Everly Petty.

Even though the notion of kicking back in a hammock sounds antithetical to everything he’s ever believed in, or practised, he said, “I just have to learn to rest a little bit, like everyone’s telling me. I need to stop working for a period of time.

Still, he confessed, “It’s hard for me ... If I don’t have a project going, I don’t feel like I’m connected to anything. I don’t even think it’s that healthy for me. I like to get out of bed and have a purpose.”

Petty always had a purpose, and a man like that, a man with a purpose, should have had more time – weeks, months, years – to practise what he called fishing and others call songwriting.

“It’s kind of a lonely work,” he said, “because you just have to keep your pole in the water. I always had a little routine of going into whatever room I was using at the time to write in, and just staying in there until I felt like I got a bite.

I was one of many blindsided by the news of his death on Monday. As we sat, just a few days earlier, he was vibrant, full of enthusiasm, still the epitome of the coolest rock star you’d want to sit down for a chat with. He laughed easily and often, occasionally dropping his voice into a softer mode when outlining just how precious his band, his music and his family were to him. The only gripe he had was about the hip he cracked soon before the tour started, which he was now finally addressing.

This is not the Tom Petty story I intended to write because I intended to write a “next stage” story.

Everyone assumed – fully expected – there would be time for this fisherman to add yet more to the bevy of beloved songs that have integrated themselves into American popular culture. Classic-rock staples, including Breakdown, American Girl, Refugee, Even the Losers, Learning to Fly, Listen to Her Heart, Here Comes My Girl, Walls and Mary Jane’s Last Dance.

“To go into a studio and hear a band play (one of his new songs) for the first time is always exciting,” Petty said. “And usually when they play it, it became something I hadn’t even pictured. Yes, I love the studio. I love the studio as much as I love playing live, easily. I’m pretty much in one every day, and I’m still at that.”

This wasn’t supposed to be the end of the road for Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, even though the group’s namesake talked about what might cause that to happen – one day, perhaps, far down the line.

“If one of us went down,” he said, “or if one of us died – God forbid – or got sick,” his voice trailed off at the thought of it. “We’re all older now,” he said softly. “Then we’d stop. I think that would be the end of it, if someone couldn’t do it.”

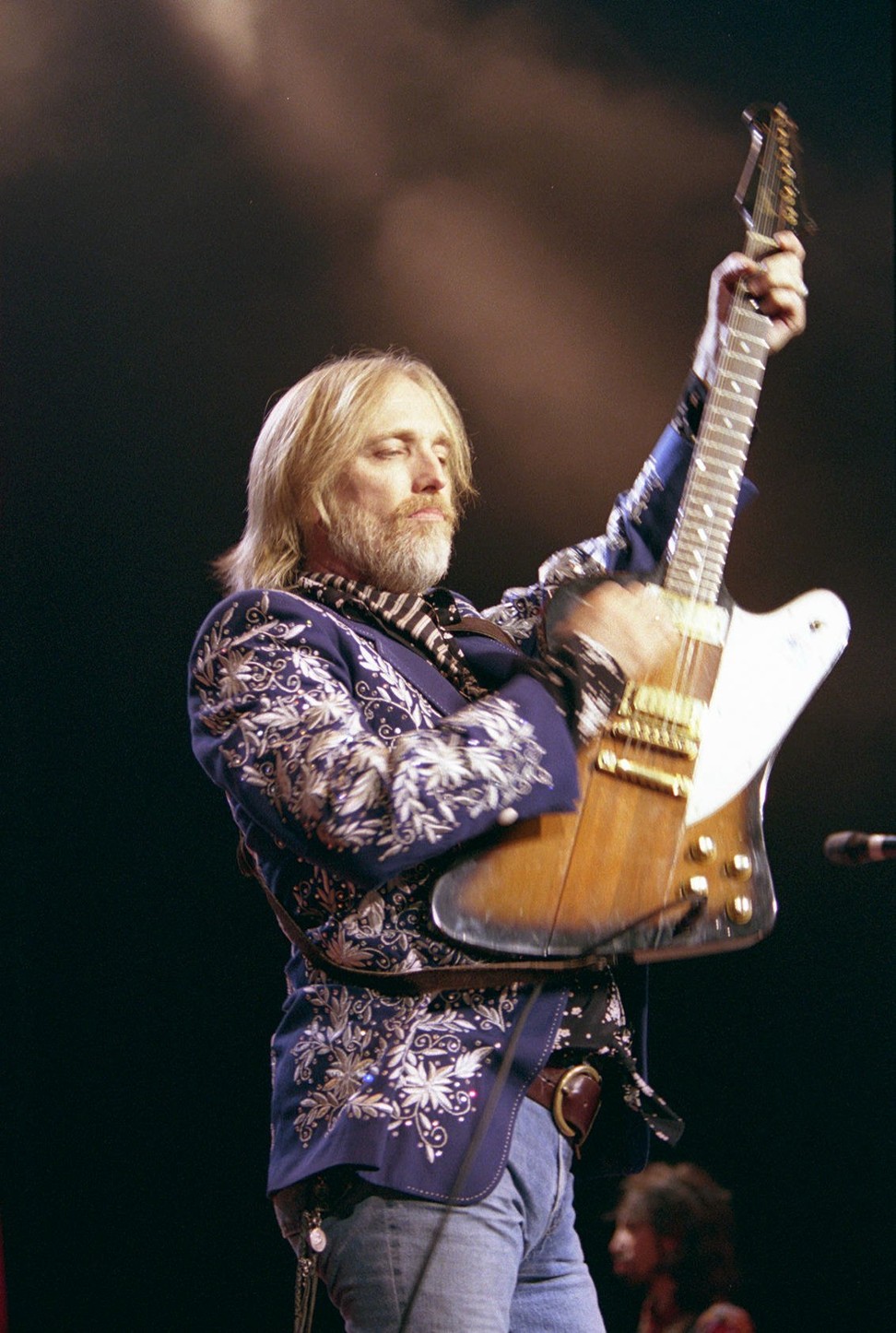

Until then, he said, there would be no talk of any proscribed retirement day – for this singer, songwriter and guitarist, or his band of brothers. “On the back side of your 60s, most people aren’t working,” he said with an air of pride. “This keeps us young. I think it keeps me young.”

Not that he had any near-future plans for a tour as extensive as the 53-show 40th anniversary run.

“It is gruelling to do a very, very long one,” he said. “This was quite a long one. It’s sometimes physically hard. But then the lights go down, you hear the crowd and you’re all better. You feel like, ‘OK, let’s do it’.”

Besides, Petty already seemed to have weathered his allotted bout of infirmity during August when he came down with laryngitis and had to postpone a few shows.

Did the incident spook him?

“Yeah, because I don’t think I’ve missed a show in many, many years,” he said. “It freaked me out so bad, because it came out of nowhere. ... My doctor said ‘I don’t think you’ve been sick – I’m looking in my records – in over 17 years, since I’ve seen you sick with anything. And I’m always like, ‘I don’t get sick.’ But [stuff] happens.

“My doctor said, ‘Despite great evidence to the contrary, it seems you’re human’,” he said with a laugh. “But I take care of myself on the road. If you’re a singer, you’ve got to be responsible, it’s a physical thing, you have to be in shape. It’s athletic. I have to make sure that I get enough sleep, that I eat right, that I don’t abuse my voice. Don’t talk too much. Don’t go to the bar and talk for three hours if you have a show the next day. I’ve learned that it’s just instinct, it’s built into me from all the years of touring.”

After six months on the road, Petty was supposed to get time to forget about those rules, just a little.

“The only happy thing about being off the road is I don’t have to worry about keeping myself ready to go the next day,” he said.

If this were the story I had intended to write, if everything had gone the way it was supposed to, Petty and the Heartbreakers would still be looking down the road at more chances to engage in the unique form of worship known only to those who’ve spent decades together in recording studios, cramped vans, dingy bars and anonymous hotel rooms.

“It was about moving people and changing the world, and I really believed in rock’n’roll – I still do,” he said. “I believed in it in its purest sense, its purest form. ... It’s unique to have a band that knows each other that long and that well.

“I’m just trying to get the best I can get out of it,” said Tom Petty, head Heartbreaker and fisher of music, “as long as it remains holy.”

That, in retrospect, is the part of my story on Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers that is, and remains, exactly as it was supposed to be.