Renowned marine biologists prepare report card on Hong Kong’s sea life

Couple dubbed Dr Doom and Dr Gloom for their prescient warnings of man-made damage to coral reefs say at first glance city’s waters are in better state than expected, and are encouraged by success of recent fight against shark fin trade

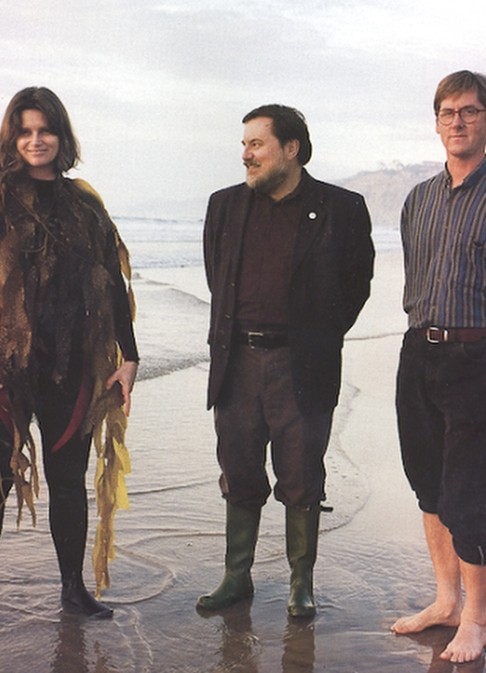

There was a time when the US media tagged Jeremy Jackson and Nancy Knowlton as Dr Doom and Dr Gloom. The two American scientists were dismissed as scaremongers for forecasting bleak scenarios of dying coral reefs and devastated marine habitats. But the two early advocates for ocean conservation have since been vindicated.

Sometimes described as rock stars of marine studies, their standing now transcends the realms of science: both are cited extensively by their peers in the world of academia but they are also particularly adept at communicating the basics to regular people.

Jackson’s 2010 TED lecture, titled “How we wrecked the ocean”, has been viewed by more than 538,000 people. Knowlton is widely regarded as “the queen of marine biodiversity” and her Ocean Portal website, which she hopes to have translated into Chinese, attracts more than two million visitors annually.

The pair were in the city recently to help mark the 25th anniversary of the Swire Institute of Marine Science (Swims), a research centre under the University of Hong Kong’s science faculty. More importantly, it marked the start of their three-year visiting professorship at Swims. During this time, they will spend a month each year in Hong Kong, working in its polluted waters and along its rubbish-strewn coastline.

Their impetus was to explore collaboration with Swims on a long-term international study of coastal marine biodiversity and ecosystems, which Knowlton helped set up. Called the Marine Global Earth Observatory (Geo) project, the study is directed by the Smithsonian Institution, where she is the Sant Chair for Marine Science.

“Hong Kong will be part of this pioneering network looking at global changes in coastal biodiversity” and Swims will be the first participant in Asia, she says.

As well as being joined in their commitment to study and protect the world’s oceans, the two marine scientists are married to each other. They fell in love while immersed in the pure scientific study of coral reefs in Jamaica during the 1970s. At the time, neither had any interest in conservation. As Jackson concedes, he was “having a joy ride” exploring the reefs when one day, everything changed for them.

“In 1980 Hurricane Allen happened – I think it was the second strongest storm in recorded history in that region and it wiped out the reefs almost overnight,” Jackson recalls.

“So we brought all the top scientists back to the reef. We were the world leaders [on reef ecology] and this was a very well studied reef; so we published the first classic paper on the impact of a powerful cyclonic storm on a coral reef – and we made some confident predictions about how it would recover .

“But we were 100 per cent wrong.”

The reef did not recover and, “the entire Caribbean really went to hell”, he says.

In subsequent years, Jackson observed reefs were dying elsewhere, and concluded that this was due to “the cumulative impact of people”.

As Jackson and Knowlton tried to warn the scientific community about the scale of marine destruction unfolding around the world, they often found themselves out of sync with orthodox thinking.

“This was a disastrous degradation of coral reefs and I was angry that some coral scientists were still using the term ‘pristine’ – just because you put on diving gear does not mean you are looking at a pristine ecosystem,” says Jackson. “I took a lot of flak for making such pessimistic statements.”

To try to understand what pristine marine ecosystems really looked like, Jackson assembled an international team of ecologists, anthropologists, archaeologists and historians to use “historical ecology” to reconstruct what marine ecosystems have been like over the past several hundred years.

Their first paper, published in the journal Science in 2001, with Jackson as lead author, sent shock waves that extended beyond the scientific community.

It showed that what scientists had been studying were not pristine marine ecosystems but habitats that had already been severely compromised by human intervention and overfishing over hundreds of years.

The team found that overfishing predated any other major disturbance to marine ecosystems and that problems such as pollution, destruction of habitats, disease and climate change, all came much later.

The paper remains one of the most cited in marine ecology.

“I had to be all ‘doom and gloom’ to persuade people the sky really was falling in,” explains Jackson, a professor at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, California. “Only when you get people to accept the reality can you start to affect change.”

But Knowlton and Jackson believe that over the past two decades, there has been enough of a ground shift in public understanding and perception about marine conservation that people can start talking about solutions.

Knowlton says: “I think there has been a genuine realisation that the ocean is in trouble, probably from the beginning of the 1990s and continuing to this day.”

That’s why she made a conscious effort to be more positive after setting up the Centre for Marine Biodiversity and Conservation within the Scripps Institution.

“When I set up the centre, I regarded it as a ‘medical school for the ocean’. But then I realised you don’t learn to write obituaries at medical school – you learn about supporting life,” she says.

These days, she is keen to highlight the success stories in conservation through initiatives such as Ocean Optimism, a collaborative movement that helps to identify links and solutions to tackle problems.

There are signs that some sharks populations are returning after years of decline. Island nations are also discovering that sharks are more valuable as live eco-attractions for divers than dead for their fins.

In protecting habitats, Knowlton points to wins in the establishment of marine sanctuaries including the extensive Great Barrier Reef, although it faces problems as a result of fertiliser run-off from farming. Similarly, fish populations at Cabo Pulmo in Mexico have bounced back by more than four times since the area was designated a marine park in 1995.

On controlling fishing levels, she cites examples such as Chile, where small fishing communities have formed cooperatives to manage the collecting of prized species that had been declining because of over-harvesting.

Jackson jokes: “They used to call us Doom and Gloom but now they call us Hope and Change.”

A recent study of 90 reef locations in the Caribbean, with data going back to 1970, points the way forward.

“We found coral cover was replaced by weed due to disease and lack of grazers like parrot fish and sea urchins. This was happening because of overfishing. Even now, some places still have 60 per cent coral cover and some places have zero,” Jackson says.

But in trying to figure out why some reef sites were doing much better than others, his team discovered that “the big decline in coral reefs is not due to climate change, it’s local factors”.

“Climate change is being used by governments as an excuse to avoid taking action,” Jackson says.

They looked at factors including governance,GDP, local population density and the level of fisheries regulation to determine coral reef health.

“Using economic data, I can predict coral cover better than I can with biological data,” he says.

Once this is widely understood, communities can push their governments to implement measures that will directly improve ocean habitats, while the longer term threats of warming and acidification are addressed, Jackson says.

Both scientists believe the same applies to Hong Kong, where they think there is much to be proud of in coastal waters, including the state of its corals.

“The corals here are indeed remarkably better than I would have expected although they don’t form large reefs,” says Jackson.

Despite the obvious economic benefits that maintaining marine biodiversity brings to fisheries and tourism, he fears the notion may be “a very tough sell” in Asia .

Still, he views the success in combating the shark fin trade in Hong Kong as a positive indicator of change. “It’s a rapidly changing local dynamic and it’s not just a victory for Hong Kong, it’s a victory for sharks.”

These recent signs indicate that Hong Kong’s seas might not be condemned to a future of doom and gloom after all.