Hongkongers mix English and Cantonese into new language, Kongish

Born as a language of protest, Kongish – a humorous mix of Cantonese and literal English translations from the local tongue – is gaining currency among bilingual young Hongkongers as a badge of identity

It takes a bit of lateral thinking to make sense of Philip the Buster. A song by Hong Kong indie band GDJYB, it features all-English lyrics but not ones most English speakers would understand.

This is a form of Kongish. “It’s a distinct language that is unique to bilingual Hong Kong people,” says Soft Liu, the band’s lead singer.

Watch: Learn some Kongish, a new language mixing English and Cantonese

“Philip the Buster is about the absurdity of the government. Although some people think filibusters hold up Legislative Council proceedings and waste taxpayers’ money, we need them as the administration rushes to implement unpopular policies,” Liu says.

Hongkongers have often taken creative liberties with the use of English and Cantonese but a growing sense of local identity in the post-colonial era has fuelled the development of Kongish. And among youth of the “umbrella movement” protest generation, it has assumed an even more prominent role as creative groups make use of the linguistic mish-mash in their works.

An example is the recently established Kongish Daily, which explains on its Facebook page: “Kongish ng hai [is not] exac7ly Chinglish ... But actcholly, Kongish hai[is] more creative, more flexible, and more functional ge variety.”

GDJYB itself is a Kongish invention (the band coined its name from GaiDan Jing YukBeng, transliteration of Cantonese for steamed egg and pork mince).

Formed in 2012, the all-girl band describe their music as maths folk with lyrics that reflect the concerns of Hong Kong people.

WATCH GDJYB single Double No No

Hence Kongish songs such as Double NoNo. The title is a literal translation of siong fei, or double negative, the Cantonese phrase referring to the children of Chinese families who gained residency despite neither parent being a resident, because they were born in Hong Kong.

The repeated chorus – “the Friso [milk powder] is mine, the Yakult is mine” – is an expression of anger at the problems that bulk grocery purchases by an influx of Chinese visitors has created for residents.

“We open the song with ‘tick tock, tick tock’ which describes the tempo of our city life,” Liu says. “As the song progresses, city life turns grim; locals always have to compete with Chinese for resources. The Hong Kong we live in is a place we no longer recognise.”

Kongish is gaining currency as more locals seek to establish a Hong Kong identity amid political turmoil, says Lisa Lim, an associate professor of English at the University of Hong Kong who studies new variants of language use.

“Using Kongish is like a badge of identity,” Lim says. “Hong Kong people are taking ownership of their multilingual language resources and are using them in a creative way to express their identity as a Cantonese and English speaker, who is not the same as somebody from China.

“During the [umbrella movement protests], there was an ‘add oil’ machine [an online platform] that relayed messages of support from people worldwide to the protesters. The phrase ‘add oil’ [a colloquial expression of encouragement] is not readily understandable by other English speakers.

“But with language, the more it is used, the more it will get known.”

Its adoption is similar to the Singlish word kiasu, which comes from Hokkien, or Fujian, dialect and means “fear of losing out”, Lim says. “It’s very informal. It’s not an English word. But over time, people started using [kiasu] in newspapers and parliament. It then got picked up by British newspapers and became more and more widely used. In 2007... it entered the Oxford English Dictionary.”

Kongish is produced in several ways. There is transliteration – phrases such as chi sin, a romanisation of Cantonese slang for crazy. Then there are literal translations: “blow chicken”, for instance, is translated from the colloquial for rallying people to a cause.

Brimming with quirky vernacular phrases, Cantonese is a lively language that provides plenty of material for humorous expression and rich imagery. (For instance, ham sup, combines the Cantonese words for salty and wet to create the description for lewd and chi sin, which describes nerve fibres being stuck together, means crazy).

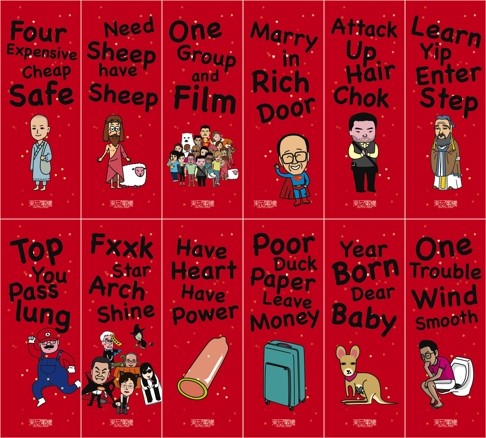

The fun of using Kongish first prompted graphic designer Tony Leung to invent his own. Now, he combines them with his own drawings and designs to create products under the brand Tony Electronic.

Presented with Cantonese and Kongish captions, the drawings on his Facebook page have attracted 40,000 likes. Satirical magazine 100Most collated the illustrations and published them in two books in 2013; his works have also been featured in advertising campaigns.

Kongish reflects many Hongkongers’ poor grasp of the English language, and provides easy material for laughs, Leung says.

“My English is not good; English education stopped at Form Five for me. I am also too lazy to look up words and phrases in the dictionary. So I just do Cantonese transliteration. Local people understand what I want to say and they find it funny, which gave me the idea to use Kongish captions to accompany my drawings.”

While people like Leung find it entertaining to play with Kongish, three lecturers of English – Nick Wong Chun, Pedro Lok Wai-yi and Alfred Tsang – have taken it up as a cultural venture. Together with two friends, the trio launched Kongish Daily, a Facebook page introducing phrases, sentences and satirical posts in Kongish, as well as pop songs with lyrics rewritten in Kongish.

Since its launch five months ago, the page has attracted more than 31,000 likes. The venture is financed by Tung Wah College as a project to study the linguistic and cultural characteristics of Kongish.

The absurdity of teachers promoting a grammatically incorrect form of English to people with poor command of the language is not lost on the founders.

Wong, who teaches at Tung Wah College, says students should know that there are different varieties of English in the world.

“Classrooms [generally] teach formal langage. Local students tend to use bookish English they learnt from school in all situations. They don’t know how to use conversational English to talk to foreigners when they are overseas. “As long as they know the distinction between Kongish and proper English, parents shouldn’t discourage their kids from being exposed to it as it forms such an important part of young people’s lives.”

“English is now a global language. Once you have a language that is global, then in a way the ownership of the language has to change. The questions of who sets the standards and who should control how we use it become very fuzzy – especially when English is used by people who speak a language like Chinese that comes from a very different family and has very different grammatical structure and pronunciation.”

A Singaporean who has lived in Hong Kong for six years, Lim adds: “Languages are constantly evolving and new varieties of English are developing ... It’s a very natural process. I am a proponent of such changes as mixing languages is a natural part of how we express ourselves as human beings.”

Wong finds that social media tools and instant messaging are helping to spread the use of Kongish.

“Typing Chinese [characters] on Whatsapp is troublesome. So many locals, including people like us, use Kongish on Whatsapp. Of course we can easily switch to standard English with correct grammar if we want,” he says.

“There’s tacit agreement between people using Kongish to communicate. For example, we type faiti la to urge people to be faster. We of course will not communicate with foreigners like that as they won’t understand what we are talking about.”

Speedy communication technologies are certain to speed up the process of language mixing, Lim adds. “Two decades ago, the English used by Hongkongers was closer to a standard variety and less mixed. The younger generation, who are bilingual, have more opportunities to use two or three languages in various contexts. Computer-mediated communication like texting and Facebook lets young Hongkongers use languages without the same constraints. [Previously] they used English in formal domains and Cantonese in informal domains.

“Unlike writing essays in school, the rules for writing online are different. In social media, people are free to express themselves. The dissemination of language is way easier and speedier. In the past, it would take decades for innovations in a new language variety to spread, be accepted and established. [But now], things just catch on online and go viral.”

Riding on the popular response to Kongish Daily, the team plans to launch a channel on YouTube, says Tsang, who lectures in English at the University of Science and Technology. Besides presenting news broadcasts in Kongish, “we will also make videos of different scenarios in daily life to illustrate how Kongish is used in different situations”, he adds.

#SoHongKong – for more stories about what makes Hong Kong unique, search for this hashtag.