Can’t get a Hong Kong flat? Try boat, or shipping container instead

Retiree who sleeps part of each week on boat asks why more Hongkongers don’t live afloat; other options for those priced out of market or waiting for public housing include co-living spaces and, if approved, cargo containers

Relaxing on a hammock at the top deck of his 17.5-metre boat anchored 200 metres off Sam Mun Tsai pier in Tai Po district, retiree Jacky Leung soaks up the view of blue skies and green peaks around Plover Clove. Leung lives in a flat with his family, but chooses to sleep on the boat two to three nights a week. Who can blame him? He has 1,500 sq ft of space here – compared to 300 sq ft at home – that costs only HK$1,500 a month for anchorage.

Leung believes life afloat could be an ideal stopgap measure for young couples struggling to find affordable housing. But his advert offering the floating home for lease landed him in hot water with the Marine Department earlier this year.

“I have friends who’ve had to remain apart since they got married, and others living in subdivided flats. Why can’t they buy a boat to live on?” says Leung, who bought his for HK$300,000 several years ago, and points out that a car parking space costs about HK$1 million.

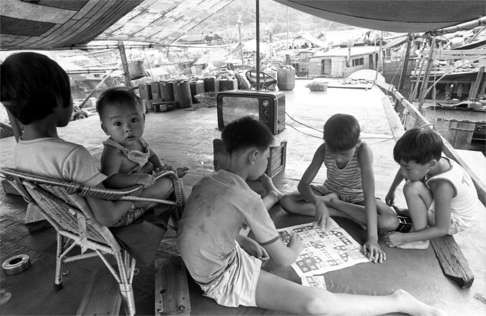

Leung says he had also hoped to help revive the centuries-old tradition of living at sea in Hong Kong, where fishing was a major industry until the 1960s, when more than 10,000 boats plied their trade.

The shortage of housing has been a perennial hot button issue for the Hong Kong administration, and flat prices have become increasingly out of reach for many residents – especially the young.

According to government statistics, more than 90 per cent of Hongkongers under the age of 25 still live with their parents. To be eligible for public housing, single applicants must earn no more than HK$10,970 per month. Even when the requirement is met, it can be take more than 10 years to be allocated a flat because the elderly and families top the waiting list.

Watch: Can a capsule solve housing affordability in Hong Kong?

Young people who came out onto the streets during the 2014 Occupy protests citied the inability to live independently due to exorbitant property prices as a major grievance – although it was essentially a protest against the failure of political reform.

Seeking to address the problem, the government announced a scheme that same year to build hostels in Jordan, Mong Kok, Sheung Wan and Tai Po, with rooms for let to young people at a discount to the market rate. The hostels are still under construction and no date has been given for their completion.

Accountant Hugo Kwok and friends have come up with a solution to help young couples move out of their parents’ homes until they can find a more private solution. In April they formed a collective called Tai Tung Co-housing, to help young couples cohabit apartments with other couples. The rent per person is about HK$3,000.

Writing in the Hong Kong Economic Journal, Kwok says the concept of co-living also entails joint responsibility for household chores.

In recent years, a culture of co-living arrangements for friends has taken root in Tokyo and Taipei, crowded cities that face housing problems similar to Hong Kong’s. 9floor Co-space in Taipei accommodates about 60 flatmates in 10 apartments.

Kwok writes that co-housing is an appropriate lifestyle option for young people living in a modern capitalist society.

“Our target is people who can’t afford rent ... and want to meet more new people to expand their social network. By sharing rent, their cost of living can be reduced. Many people think that they don’t want to interact with others after work. They think that a home should be a totally private space for relaxation. [But] if interpersonal relationships are confined to only the work environment, will people become more alienated and self-centred in their downtime?”

The council’s idea is based on a concept pioneered in the Dutch capital, Amsterdam, which launched a scheme to provide temporary student housing more than a decade ago. The stacked containers, each measuring about 200 sq ft, are insulated and fitted with a bathroom, open kitchen, air conditioner and windows. The homes can withstand most climatic conditions, according to planners.

“In 30 years working as an architect, I’ve seen people’s homes getting smaller and smaller. Property developers see housing as a commodity to maximise their profits, instead of a place for people to live,” he says.

“Such unconventional living concepts as shipping containers are not new. The idea was proposed by academics some years ago. For such temporary housing, you have to find land to house them. And you have to go through the Town Planning Board and [district councils] and so on.

“At some point in the future, you have to relocate the people living there, so it needs a comprehensive plan … The time needed to complete all those procedures might be similar to that for construction of a public housing estate. In the long term, the government has to identify land for constructing permanent housing for common people, not luxury property buyers.”

Boating enthusiast Leung, who worked in the maritime trade before retirement, is adamant that living on the water should not be ruled out in Hong Kong, although he concedes it’s not a long-term solution – especially for landlubbers who get seasick.

Acquiring a leisure boat licence is easy, he says. “You just need to know how to swim a short distance and finish an exam paper of multiple-choice questions. “Afterwards, you get an instructor to teach you how to pilot the boat. It’s easier than playing video games.”

It’s not all plain sailing, though, Leung admits. There are practical concerns, such as water and electricity supply, but he overcame them using his nous. He had solar panels installed on the top deck to provide electricity for a fridge, heater and stove. A diesel generator powers hungrier appliances, such as the air conditioner, but he says he rarely uses it.

Leung also built a water retention pool on the boat’s roof, connected to pipes extending downstairs to the kitchen and toilet. “A downpour can yield more than 2,000 litres of water, enough for my whole family of four for a week. I can also go ashore to get water, but it’s troublesome,” he says.

“The biggest difficulty is the need for a feeder boat to go ashore. I have one myself which I bought for tens of thousands of dollars some years ago.”

On the October day we visit, the roof of the boat is blistering hot because his tarpaulin cover had been destroyed during a typhoon. Leung says other maintenance costs have been negligible.

“Renewing my leisure boat licence costs only HK$2,000 a year, and insurance sets me back HK$5,000 a year.”

It’s all worth it, he says. “I lived near the Yau Ma Tei typhoon shelter when I was young, so I’ve always loved the sea. I love jumping into the water after I wake up, and looking at the starry night sky from the deck.”