London celebrates century of Chinese cinema

Curating a celebration of Chinese films in London meant working with government officials and rights holders on the mainland, Hong Kong and Taiwan, writes James Mottram

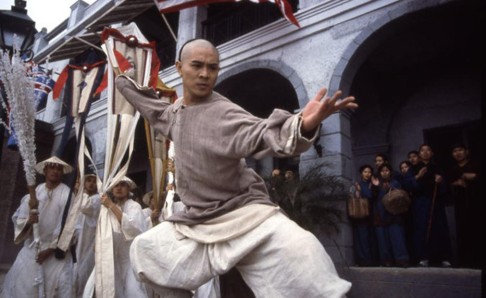

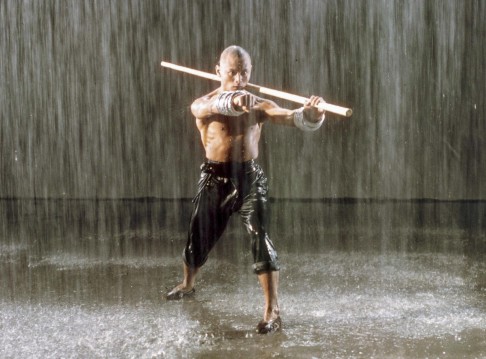

It's a weekend afternoon at London's BFI Southbank. A line of people are waiting for returns for the sold-out screening of The 36th Chamber of Shaolin, Lau Kar-leung's sumptuous 1978 martial arts masterpiece starring Gordon Liu Chia-hui and one of the more than 80 films playing as part of a five-month-long celebration of Chinese cinema.

Screening films from the mainland, Hong Kong and Taiwan, "Century of Chinese Cinema" is the most comprehensive exploration of its kind mounted in the West. And judging by the packed auditorium of viewers watching the Shaw Brothers classic, it's hugely popular.

Augmented by lectures, events, on-stage interviews (Hong Kong New Wave pioneer Ann Hui On-wah is due in on August 24) and even a new, illuminating British Film Institute (BFI) book of critical essays, Electric Shadows, it is curated by Noah Cowan, artistic director of the Toronto International Film Festival's Bell Lightbox facility, where the season first played last summer.

"The 'Century of Chinese Cinema' programme is something of a miracle," Cowan says. "When we began, I didn't actually believe we would be able to successfully collaborate with all the various entities which finally helped to make it happen. In that respect, the programme is something of a milestone."

A trailblazing collaboration with the China Film Archive, the Hong Kong Film Archive and the Chinese Taipei Film Archive, it often involved "bizarre conversations" with government officials and rights holders to get hold of certain films, he says. "It's been quite a journey to get to where we are."

"The impetus for me is that Chinese [cinema], taken as a whole, stands shoulder to shoulder with any great national cinema," says Cowan, "be it French cinema, or Hollywood, Bollywood - you name it." And given the dazzling array of films on show - many previously unavailable to British audiences - it's hard to disagree.

Cowan admits the purpose of the season was to provide an "entry-point" for non-Chinese speakers into Chinese cinema. But audiences - as I witnessed at the screening of The 36th Chamber of Shaolin - have also boasted a strong number of Chinese viewers.

"One of the most beautiful things about what happened in Toronto, and I think it's happening in London too, is the influx of young [Putonghua] speakers - who mostly had recently emigrated from the mainland - to the screenings of Hong Kong films," says Cowan. "They had heard the music, often, but hadn't been able to see the films. Equally so, some Taiwanese friends were really excited to see some of the 1950s and 1960s mainland films which remain officially unavailable in Taiwan, as they were at war - officially - at that time."

Then there are the films of Fifth Generation auteurs such as Chen Kaige and Zhang Yimou - with the season offering rare chances to see their respective directorial debuts, 1984's Yellow Earth and 1987's Red Sorghum, among others. Their work in particular offers a lesson to others in how to direct period epics, Cowan says. "You look at something like Oliver Stone's Alexander," he says. "He's looking a lot more like Chen Kaige than he is old Hollywood to envisage that kind of a movie."

As Cowan notes, for Chinese viewers, there is less of a distinction than in the West between genre and art-house cinema. "They're seen as dealing with similar story arcs, with similar cultural tensions." While genre films in the West tend to be viewed by young males, leaving the art-house movies to older viewers, "within the Chinese-speaking communities, there's a love for both".

Cowan says "one of the interesting filmmaking journeys occurring right now" is the fate of Hong Kong cinema. "The biggest and most important filmmakers have either relocated to [the] mainland or they're there most of the time. And so there's the dramatic decline in major Hong Kong film production, but also it's increasingly lacking mentors … to spur a new generation of filmmakers," he says.

Does he see this as worrying? "It is, but on the other hand you have all these new opportunities related to the mainland being next door."

Cowan feels Hong Kong directors may flourish in politically oriented films. "There's always been a careful vanguard-ism among filmmakers working in Hong Kong, just to push the political conversation forward about how the history and culture of the region might push all Chinese-speaking places forward. It did this gently for Taiwan, it did this gently for the mainland, through its cinema. Change is happening at a pace no-one anticipated right now, but it's extremely unclear what the coming political evolutions will bring," he says.

With Hollywood offshoots such as Legendary Pictures East attempting to foster co-productions with Chinese companies, this spirit of East-meets-West looks set to continue. What that will mean for homegrown Chinese product remains to be seen. But whatever happens, as Chinese cinema enters its second century, it's going to be fascinating to watch it unfold.