Hong Kong film’s golden era shown in Shanghai photo exhibition

Portraits from the 1950s onwards include Hong Kong actors and actresses, and political and nationalistic themes from the Cultural Revolution

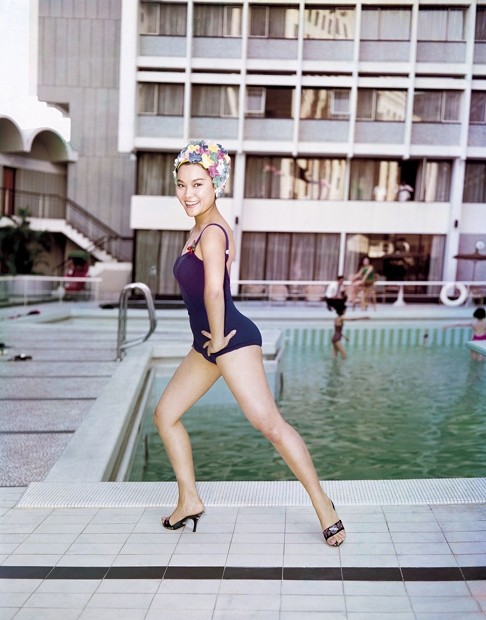

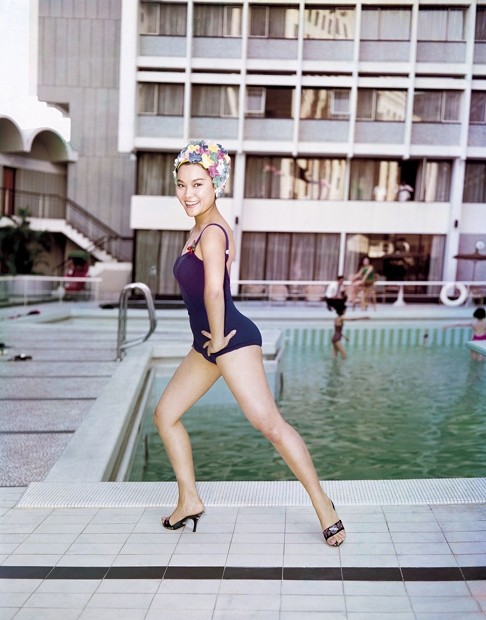

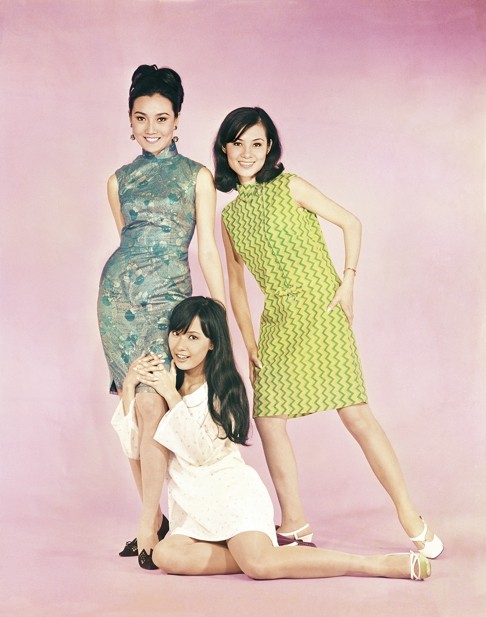

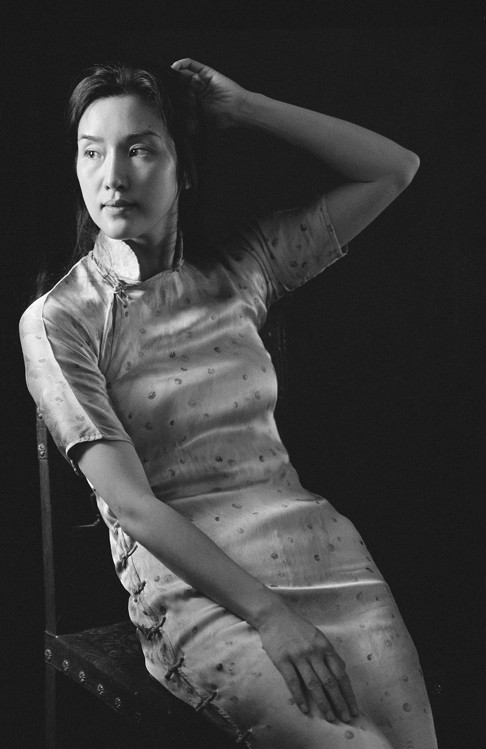

A 1970s Shaw Studio starlet looks out from beneath long eyelashes, with perfectly shaped eyebrows, big hair, a coy smile and wearing a form-fitting qipao – it’s the golden era of Hong Kong film and a period of romantic nostalgia.

The image, taken by Yau Leung, is one of striking pictures featured in the “Figures of Speech” exhibition at the Shanghai Centre of Photography, which showcases Hong Kong portraiture from the 1950s onwards. Yau’s work was discovered by exhibition producer (and gallery founder) Liu Heung-shing inside shoe boxes of negatives from the photographer’s estate.

“Looking back at the 1960s and ’70s, we can’t help but hold on to those collective memories.This remains the allure and power of the photography. It is no different from how the French would adore those iconic Brigitte Bardot pictures,” says the Hong Kong-born Liu.

Liu and Smith’s choice of six photographers might at first seem random, with each artist bringing something very different to the table. But this wide spectrum is intended “for the Chinese public to learn about Hong Kong.”

“I feel Hong Kong’s photography has had its own development from the colonial days to the present, and the social and economic context for Hong Kong photographers is vastly different from that of the mainland,” says Liu.

Works range from Yau’s glamorous famous and aspiring actresses, to Meng Minsheng’s staged political, nationalistic works from his “Imitated Revolution” series. There is the more conceptual work of duo Sara Wong and Leung Chi-wo, who investigate Roland Barthes’ ideas of photography and temporality through self portraits restaged from anonymous figures found in old newspaper and magazine pictures.

“I love the frame of the photographer posing as a US sailor taking pictures. I saw plenty of that in the ‘60s in the streets of Wan Chai. Sara and Chi-wo’s works are clean images full of ambiguity, personal identity and memories.” says Liu, who is himself a veteran photographer and Pulitzer prize winner.

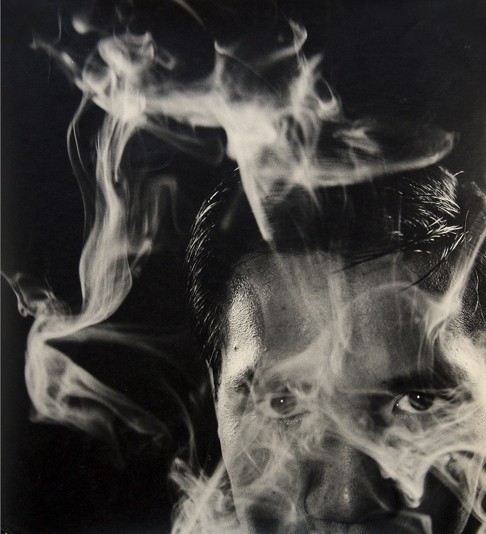

Iconic Hong Kong photographer Fan Ho took much inspiration from the city , but the exhibition presents his powerful, dramatically lit portraits of stage actors and photographer friends instead of the street scenes that people are most familiar with. Ho, who now lives in San Francisco, came from the film world and eventually became a filmmaker. His expert darkroom skills, Liu says, “precede today’s Photoshop work”.

There is the almost surreal, Biblical symbolism in Stanley Fung’s black and white pieces – all an ode to the religion that was so important to him. “Stanley is unique,” says Liu, “I learned so much just listening to him. He came across as someone totally genuine, and it shows in his photographers of believers. Many people are moved by this.”

“These give mainland viewers suppressed smiles, at least to those who are old enough to remember the brutal Cultural Revolution,” says Liu. “Meng Minsheng shows that lots of folks on the left did have certain illusions about China in the height of that tumultuous era.”

Liu says “portraiture as fantasy” is a worldwide phenomenon and this exhibition is about showing what Hong Kong photographers have done in different periods of its history – and this is something many mainlanders are unaware of, especially those of the post-80s generation.

“It will direct Chinese sensibilities not only to the arts of photography, but also how Chinese themselves relate to the world. Photography is an increasingly popular world language.”

The gallery has become a key part of Shanghai’s growing West Bund arts scene alongside more famous institutes such as the Long Museum and Yuz Museum. And for many, a critical element of cultural development on the mainland will be spaces like this that are independent and privately driven.

On a personal, level, the Shanghai Centre of Photography is milestone for Liu. He shared a Pulitzer for his work documenting the collapse of the Soviet Union at the end of the cold war. Today though, his body of work largely focuses on China, after Mao to the present, and is very much “still a work in progress”.

Liu says his photography can serve as a reminder to Chinese pundits that “the story from rags to riches is incomplete when China negates its own history”.

As lenses are drawn increasingly towards the country’s breakneck and sometimes volatile development, Liu has some advice for aspiring Hong Kong photographers seeking the longevity he enjoys.

“I would wholeheartedly encourage them to fully leverage the huge potential of China as a subject. China remains under-photographed if we remove all of the clichéd images.”