by Colm Toibin

Picador

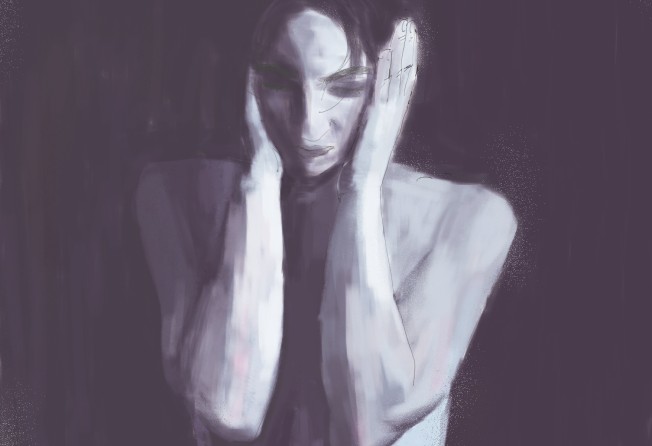

Colm Toibin's novel captures a woman's struggle with grief and widowhood in Ireland of yesteryear

Irish novelist Colm Toibin's new novel, Nora Webster, transports the reader into the mind of its title character with such immediacy that one can almost feel her holding her breath as neighbour Tom O'Connor says: "You must be fed up of them. Will they never stop coming?"

He is, we discover, referring to the endless procession of visitors that come to her Enniscorthy home in Ireland's County Wexford each night, offering polite condolences in the wake of her husband's death. But in this moment all we know is that Nora realises "he was using a new tone with her, a tone he would never have tried before. He was speaking as though he had some authority over her."

It is only later that night, after her youngest son, Conor, ushers "the little woman who lives in Court Street", May Lacey, into the house for some more polite, strained and nosy conversation that we begin to discover the nature of Nora's bereavement and how hard she works at disguising how she feels.

Toibin is, of course, famed for his almost preternatural skill in giving authentic voice to female characters in a body of work that includes seven award-winning novels, two collections of stories, 14 works of non-fiction and innumerable essays. His novels include the Booker-prize-shortlisted works Blackwater Lightship and The Master - which also won the IMPAC Dublin prize, the Prix du Meilleur Livre and the LA Times Novel of the Year - and his 2009 Costa Award-winning novel, Brooklyn. And let's not forget his recent 2013 Booker Prize shortlisted novel, The Testament of Mary, which re-imagined the inner life of Mary, mother of Jesus in her later years - and was, as one critic put it, "his boldest jump yet".

But with Nora Webster, it seems Toibin has outdone himself. His Nora springs to life on the page in a way that astounds, confounds and beguiles in equal measure. In plain, unsentimental prose, Toibin paints a deeply convincing portrait of this 40-year-old woman struggling to rebuild her life after the death of Maurice, her beloved husband of 21 years. Difficult, fiercely private and short-tempered at times yet alert to the needs of others, Nora is left with two young sons, two daughters on the cusp of adulthood, very little money and a quiet, overwhelming despair.

Early in the novel - which unfolds over a three-year period in the late 1960s and early '70s - it's not only her neighbour who exerts authority over her, even May makes it plain that Nora should sell the family beach house in Cush to May's son, Jack Lacey. It's a request that horrifies Nora, but one to which she later agrees, even though this brings home to her and her apprehensive young sons, Conor and Donal, "something that they had been managing not to think about".

Toibin excels in giving shape and form to the inchoate - those hidden tensions, doubts, fears, desires, antipathies and anxieties that underpin everyday human interaction take on a thrilling potency in this quiet, unassuming narrative. This is not a novel that soars and dips on moments of high drama, but one that pivots, ambles and careens on small, quotidian private revelations and inner awakenings. Such as the one that ensues when Aunt Josie comes to visit without warning one Saturday in January. For Nora, who wishes to be left alone with her thoughts and her two sons, Josie's visit is both an irritation and an intrusion. But even more so for the two boys, it seems.

Sensing something unspoken in the air between them, Nora's unease grows when she observes Donal's stutter becoming even more pronounced in Josie's presence. His subsequent nightmare firms up her desire to confront Josie. She chooses a moment when her eldest daughter, Fiona, a trainee schoolteacher, returns home from Dublin for the weekend.

Leaving Fiona in charge of the boys, she drives secretly to Josie's farmhouse while telling her children she'll be shopping in Wexford. There she discovers from Josie the awful truth that Donal's stammer and Conor's bedwetting had begun during the months she had left the boys in Josie's care while she sat by their ailing father's bedside in the old TB clinic outside town. Josie had phoned her, but Nora had been too preoccupied with the dying Maurice to return the call or let the boys know when she'd return.

Another wake-up call confronts her on her return home. She is to be offered her old job back, if she will just call upon one Peggy Gibney. Meanwhile, brother-in-law Jim will give her money to tide her over if she accepts the Gibneys' offer, an idea that's bleak to Nora who fears she will lose her freedom in going back to work after 21 years of marriage. But she knows she cannot turn the Gibneys down, and so decides to have her hair done in readiness.

Nora is far from meek, but is in many ways trapped by the small-town mores she was born into as much as the grief that still engulfs her. Toibin, who hails from Enniscorthy, is a magician in the way he conveys the restraint required to keep up appearances in a provincial Irish town, the fear of the gossip that might ensue should one run foul of social norms. Nora's apprehension of the opprobrium that might follow her hasty decision to have her grey hair dyed back to its original brown is brilliantly evoked on the page, as is her reluctance to complain to the young hairdresser who is obviously delighted with her work. But when Mrs Hogan, "in her apron and a pair of very worn-looking shoes", comments on her new hair colour, Nora retorts in a manner that makes her feel brave. She also wonders "if she had ever done anything like this before in her life, acted on a whim without any thought for the consequences".

And so in a series of small, fiercely spirited moments, Nora begins to cast off her despair and the shackles of small-town convention, and find her voice. Through music and a forgotten talent for singing, she finds a way to rebuild her life. She begins by taking secret singing lessons with an elderly former nun, and is surprised by the intense pleasure she finds in music, the one thing she never shared with her tone deaf husband, Maurice.

There are other little rebellions too. She risks the ire of her well-meaning but materialistic sister, Catherine, holidays in Spain with Aunt Josie, and threatens to picket the school where Brother Herlihy has demoted Conor unless he is reinstated to his usual class.

She even attends a forbidden trade union meeting and stands up for herself at her hated job, winning the right to work part-time so she can be home when the boys return from school.

All the while, playing out in the background are "The Troubles" of Northern Ireland and the classical music melodies Nora begins avidly collecting. Dates and time are never mentioned in this unlikely page-turner of a novel where violent events such as Bloody Sunday in Derry are witnessed by a shocked Nora, her relatives and friends on TV, underscoring the ordered, gentle continuum of life in Enniscorthy where quiz nights and meetings of the Gramophone Society are highlights of the social calendar.

A rich cast of characters come and go in this superbly authentic tale, which begins in greyish hues and slowly gathers colour, momentum and melody as Nora slowly steps out into the world. Catholicism's presence, like that of The Troubles, is relegated to the background in a story which delivers a portrait of an Ireland at odds with the one held up to public scrutiny.

This is a richly detailed and luminous novel, shaded with a palpable sense of deeper spiritual force at play as a middle-aged woman discovers the simple truth of what another woman tells her: "There is no better way to heal yourself than singing in a choir. That is why God made music."