Before it's too late: Hong Kong author documents Chinese in Cuba

One man's quest to learn more about his father's time on the island has led him to record the little-known history of an obscure part of the Chinese diaspora

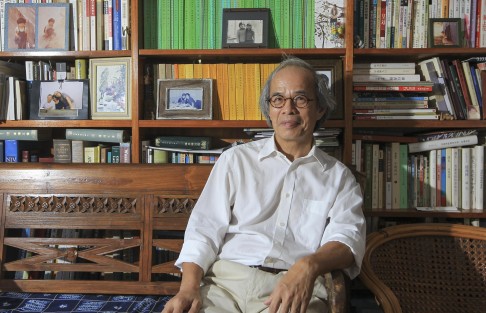

Hongkongers often have personal links with Chinese communities around the world, but former academic Louie Kin-sheun is a rare resident with a connection to Chinese emigrants in Cuba.

Both his grandfather and father established themselves in the Caribbean nation, and Louie has been digging into records and visiting Cuba over the past decade to retrace his father's journey, learn about the experiences of other Chinese there and record the history of its Chinese diaspora.

The quest began after his mother's death in 2004.

"I was tidying up her things after she died and found 200 letters from my father that described his life in Cuba [in the '50s and '60s]. I became curious and wanted to know whether there were more traces of him in Cuba," Louie says.

Louie's family originated from Taishan in Guangdong province, and his grandfather, José Luis, was among thousands of workers who left to seek a better life in Cuba.

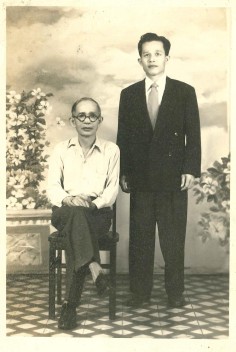

In 1954, his father, Julio Luis, left to join his grandfather; Louie was three years old.

"Most people from Taishan had to borrow from relatives to pay for the US$1,000 ship's passage to Cuba and repaid the loan after 10 years. Luckily, my grandad paid my dad's way to Cuba. He worked in the grocery business and his employer provided food and lodgings, so he could save all his income," Louie says.

By the time Julio Luis returned on a visit after five years, he was able to buy a home for his family, who had moved to Hong Kong.

"He bought us a new home in Mong Kok for HK$20,000," Louie recalls. "Hong Kong people were poor then. He made good and went around in a suit. People came to congratulate him and he distributed cigars as gifts."

However, Julio Luis' fortunes changed following the socialist revolution in 1959.

"My dad thought that the new leadership wouldn't last and … as he only spoke the Taishan dialect and Spanish, he didn't want to live in Hong Kong. But his return to Cuba turned out to be a miscalculation, which he regretted dearly," Louie says.

The Castro government's reissue of the Cuban peso and freeze on remittances, ostensibly to cut off funds to anti-Castro forces, also hit Julio Luis hard. Louie says his father could still send money home through the black market in the earlier days of the revolution, but later even that route vanished.

"In his letters, he kept apologising and blaming himself. He exhausted all avenues, even asking [Chinese] seamen to help him smuggle money home. He wanted to leave for the US to earn money but, in the end, his options ran out and he returned to Hong Kong in 1966 without a cent. Even funds for his plane ticket had to be sent from Hong Kong.

"My dad always played down bad things in his letters so as not to worry the family. During the 1961 Bay of Pigs [invasion by CIA-sponsored paramilitary forces] and the 1962 missile crisis, he wrote home every week telling us he was OK."

Julio Luis returned to Hong Kong a broken man, and died two years later.

That experience and those of other Chinese emigrants during the Cuban revolution and the upheavals of the cold war years are told in Louie's recent book, So Far Away in Cuba. It details episodes such as the imprisonment of 13 Chinese spies who ran a pro-communist newspaper in Cuba until Kuomintang officials reported them to the Batista dictatorship in 1951.

Louie's project is funded by the Lee Hysan Foundation, where he is now a researcher. It enabled him to make several trips to Cuba to dig out old documents, Chinese newspaper reports and interview emigrants, focusing his research on first-generation Chinese, many of whom came from Taishan.

On his first visit to Havana in 2010, he found its Chinatown like much of the city - poor and run down, its elegant colonial buildings decrepit. The US embargo of more than half a century left Cuba without access to resources and trade with much of the world, trapping the country, including its Chinese community, in a time warp.

As a result, the Taishan dialect spoken in Havana is so pure that it is no longer heard in China, where interaction with outsiders and widespread use of Putonghua has influenced its usage. "But in Havana they are still using archaic vocabulary and pronunciation," Louie says.

"It's a peculiar community," he says. "Isolated for more than 50 years, the community is ignorant of the outside world. They asked about the Tiger Balm Garden [in Tai Hang], not realising that it had been demolished [in 2004]."

None of the emigrants had remained in contact with their families.

As if frozen in time, that first generation of Chinese Cubans makes for an interesting group to study. "But none of their stories are happy ones - all regretted going to Cuba," Louie says. "Most are not well educated and don't think of recording their stories, but they are worth preserving."

If not for his project, this part of the Chinese diaspora's history would be lost forever.

There is a dearth of Chinese-driven research on the subject, Louie says. "The earliest presence of Chinese in Cuba can be traced to 1847, after the first opium war, when 140,000 Chinese were sold to Cuba as coolies to replace the black slaves. They helped build much infrastructure like railways."

Although there have been dissertations on the subject in Spanish and English, none exist in Chinese, which is why Louie will follow up with a second book on the Chinese in Cuba next year.

He will have access to more material: coolies' contracts as indentured servants, records of ship departure times and the like. The Hong Kong Museum of History bought the set of Spanish-language documents several years ago and commissioned him to decipher them (Louie, who earned his doctorate in France, picked up Spanish for his Cuba project).

In researching the Chinese diaspora in Cuba, Louie has fallen in love with the country.

"The weather is nice throughout the year. Cubans, like Spanish, are hedonists. Music is everywhere on the streets, with people singing and dancing. They are poor and lack many goods, but they are happy. Education, housing and health care are covered by the government. They represent a kinder socialism, which is a far cry from the confrontational Chinese socialism that I grew up with," he says.

"I wrote my book before news about the opening of Cuba. There will soon be breathtaking changes to the country."