2030 vision: 5 ways the world’s educators must adapt to the new machine age

Economist Intelligence Unit report commissioned by newly launched Yidan Prize Foundation stresses need to integrate technology in classrooms, and prioritise vocational training and adaptability

Chen Yidan, a co-founder of Chinese tech giant Tencent Holdings, wants to “create a better world through education”. That’s why he recently created the Yidan Prize.

While many philanthropic programmes take a broad-brush approach, the Yidan Prize sets itself apart with its aim of recognising enterprising efforts in areas such as the quality of school systems, integrating technology into teaching, and vocational training for a future labour market that will be defined by human-machine interdependence.

Launched in May by his Yidan Prize Foundation, to which Chen has given a HK$2.5 billion endowment, the prize is actually two prizes: there will be annual awards for research and for educational development. Each carries a HK$15 million cash prize, along with a HK$15 million project fund to advance the recipients’ innovations.

Instead of prescribing a way forward to improve quality and access to education, the initiative encourages researchers and teachers, activists as well as policymakers to find effective solutions for communities around the world.

To facilitate this goal, Chen commissioned the Economist Intelligence Unit to analyse economic and political data and tap experts from around the world to produce a report looking at the trajectory of global education in the next 14 years.

The foundation hopes this report, called the Yidan Prize Forecast: Education to 2030, will “spark conversation on education going forward”, says Christopher Claque, a senior editor at EIU who coordinated the project.

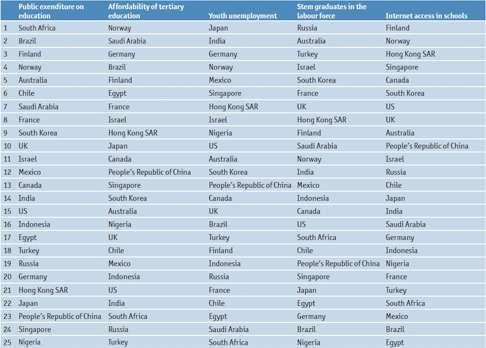

Gathered from 25 countries, the data focuses on five key indicators: public spending on education, affordability of tertiary education, youth unemployment, graduates in STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics), and internet access in schools.

Not surprisingly, countries with shrinking and ageing populations will probably reduce spending on education. Large developing economies with an expanding middle class, notably China and India, are, by 2030, expected to be spending, respectively, 2.9 per cent of GDP (up from 2.3 per cent now) and 4.8 per cent of GDP (up from 4.1 per cent now) on education.

In contrast, by 2030 cities such as Hong Kong and Singapore, both of which currently spend 3.4 per cent of GDP on education, are expected to reduce spending by 0.1 per cent and 0.7 per cent of GDP respectively.

“In Hong Kong and Singapore, there is the potential for a stagnant middle class. The populations are ageing and drawing more resources, and fewer kids are entering the education system,” Clague says. “In China, the demographic situation is similar, although a bit further behind on the curve and on a much greater scale. But the size of the middle class is growing, so spending will increase.”

Ranking education by its share of public expenditure, however, means little if cost-effectiveness is not taken into account.

“India is a [negative] example,” says Clague. “Experts there say the government is spending money on infrastructure, but teachers aren’t showing up to classes and there is no consistent evaluation of teaching.”

As the report repeatedly suggests, countries need to monitor their investments in education to ensure they are used effectively.

In the US, teacher accountability is a big part of recent reform efforts, but there has also been heated debate about whether standardised tests are a fair way of gauging the quality of teaching and student attainment.

Policymakers and educators need to work together to ensure fair, cost-effective spending that promotes equality in education rather than exacerbates inequities in school systems that are increasingly hierarchical and privatised.

Whatever their levels of investment in education through to 2030, all countries will face competing priorities for public spending as their demographics continue to shift. Given such concerns, experts interviewed for the report, such as Rafiq Dossani, director of the Rand Centre for Asia-Pacific Policy, warn that it is ever more important to set aside sufficient resources to guarantee good basic primary and secondary education.

To complement public efforts, the private sector is increasingly being tapped to bring improvements that go beyond setting up affordable schools. One popular approach is to use “social impact bonds” to compensate investors when certain education goals are reached in developing economies. This has been used in Rajasthan, India, for example, to retain more girls in school.

“Improving education is the basis for all [the UN’s] goals [for sustainable development],” notes Dr Qian Tang, assistant director-general for education at Unesco and head of the Yidan Prize global advisory board. “For this, we need support not only from governments but all stakeholders.”

The report predicts tertiary education will become more affordable in developing economies with low per capita income, where education is relatively expensive.

Use of technology in formats such as massive online open courses (MOOCs) can play a big part in making education more equitable – and thereby boost social mobility. However, this will require sustained effort to ensure high standards of implementation, curricula and achievement.

Youth unemployment is another concern: one billion young people are expected to join the global job market over the next decade. Countries that already do well now should continue to enjoy low rates of joblessness among young people, and Japan is expected to have the lowest rate in 2030, with just 6.2 per cent youth joblessness. Countries currently struggling with high youth unemployment should also see some improvement.

But with many jobs set to be lost to automation in the near future, the primary task of educators is to equip young people with adequate skills and knowledge for a changing marketplace – one marked by a coming “fourth industrial revolution”.

More than anything, the report argues that producing more qualified STEM graduates will be increasingly important. One crucial step in this direction is to increase efforts to bring young women into STEM fields, which have traditionally been male-dominated.

Delivering high-quality STEM education will be a challenge, as will making sure young people have multidisciplinary and technical skills, as well as cultural versatility to adapt to rapid changes in a globalised world, the report says.

This will require putting in better frameworks for vocational education, with more participation from real-world employers.

Many countries will have to first remove the social stigma associated with non-academic training, and learn from countries like Germany, where vocational education is respected.

And although internet access in schools will be more widespread (almost universal in wealthy economies from Finland to Hong Kong), effective use of technology in education will a challenge, the report says.

“It’s going to be a learning process with some failures, but out of those failures there will come successes, just like with any other innovation,” Clague says.

For instance, a programme in Israel to equip all teachers with laptop computers has yielded tangible results – a relatively inexpensive measure that can be adopted by developing countries.

In casting a global net for such efforts, the Yidan Prize Foundation seeks to reward people and programmes making advances in education that are “substantial, scalable, easy for others to follow, forward-looking, and future-oriented” – conditions essential for realising Chen’s vision of changing the world.