Child's-eye view

Children's book author Anthony Browne says pictures are as important as words for stirring youngsters' imaginations, writes Mabel Sieh

Anthony Browne is a great advocate of picture books, but that's not just because he creates them. He believes picture books are a crucial platform for stirring children's imaginations.

"We see images before we understand words. Images are everywhere; they are direct and universal ... Pictures are very good in conveying feelings and emotions. They can tell what words don't," says Browne, a multi-award-winning author and illustrator of children's books and the British Children's Laureate for 2009 and 2011.

That's not to say he thinks words are not important. Picture books are an integral stage, not only in developing children's reading skills but also in cultivating a passion for reading.

"I love the balance between words and pictures. I think losing either one will lose the excitement. Words tell some parts of the story and pictures tell more of it," he says. "Picture books are an art form unlike any other books. They help to develop creativity in children, who are fascinated by everything they see."

He thinks that picture books are generally undervalued and marginalised, often by parents so intent on pushing their children up the educational ladder, it can even have an opposite effect on the aim cultivating interest in reading.

"The big problem today, in Britain anyway, is that we drag our children out of picture books too early. We want them to read a 'proper' book with lengthy text and difficult words when they're not ready. So reading becomes too hard and not exciting for them.

"When you are not excited about books as a child, you won't become a reader as an adult."

The 67-year-old author was in town recently following a visit to Nanjing to present the Feng Zikai Chinese Children's Picture Books Award at a forum attended by leading critics, educators and acclaimed illustrators including Jimmy Liao and Chen Chih-yuan from Taiwan. Just as he was mobbed by fans in Nanjing, Browne received an enthusiastic welcome by youngsters at his public sessions in Hong Kong organised by the local affiliate of charity Bring Me A Book.

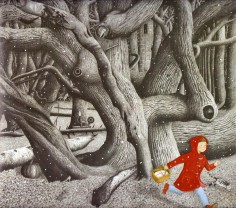

Browne is known for his lively, sometimes surreal illustrations and skilful use of colour, pattern and subtle background detail. For instance, in Voices in the Park, one of his award-winning books, he expresses the moods and feelings of four characters who happen to be walking in the same park on the same day through different colours and shades.

His idea of how words and pictures complement each other in storytelling stands out from many locally produced children's books, which are presented like textbook publishers' readers for young learners. These tend to translate text directly into pictures, repeating the same content visually and leaving little room for young readers to conjure their own interpretations.

"I believe the best children's books are those that leave a tantalising gap between the pictures and the words, a gap that is to be filled by the reader's imagination. That adds so much more excitement to reading a book," he says.

Browne's approach has much to do with the route he took to becoming a writer and illustrator. As children, he and his older brother Michael loved to draw and both received plenty of support from their parents.

"But I didn't think I drew better than anyone then," he says. "My mother was very encouraging, though. She never compared our drawings or said which was better."

His belief in the power of drawing and imagination is reflected in Bear Hunt, a story about a bear who encounters different dangers on a walk. In each incident, he takes out a pencil and magically draws something to get him out of trouble.

Does he think drawing can really help to solve problems?

"It's certainly helped me; it's given me a profession I'd never thought of. When I graduated I wanted to be an artist; that couldn't earn me a living so I worked for an advertising firm ... but I didn't like it.

"Later I wanted to be an art teacher but that didn't work out, either. I worked as a medical illustrator, too, but the drawings were too real and technical for me. I created greeting cards and I got bored of it. I never imagined I could be an author and illustrator."

At a session at the Hong Kong Central Library, he invited young fans to draw by playing the Shape Game, which he invented with his brother and inspired his book of the same name. He first asked one child to draw an abstract shape; then another child added to it and turned the doodle into something else. Finally, everyone was asked to guess what the drawing was. There was no right or wrong answer.

Youngsters, he finds, are better than adults at the game because they have "the pure sense of imagination without self-conscious and societal norms".

"The Shape Game is about transformation - you take an idea and transform it into another. That's creativity to me. I think every parent should play it with their children," he says.

Such a transformation can also be seen in his adapted children classics. Me and You, for example, is a version of The Three Bears with a surprise ending, and Into the Forest describes a boy who meets Jack, Goldilocks and Hansel and Gretel on his way to see his sick grandmother.

"When I put different ideas together in a story, it becomes something interesting and I feel most creative," he says

Browne never starts with a complete story in his head but begins by visualising different scenarios. "[It's] like making a film with a storyboard - I draw the scenes I have in my mind, then gradually the story is developed."

His books have educational themes, too, such as appreciating mothers ( Piggybook) and believing in yourself in ( Willy the Wimp).

"I'm aware of the values embedded in my stories. But I don't think too much about what lessons I want to teach [readers] when developing a story. If I do that, the creativity will disappear."

That same principle applies when parents read to their children. "They shouldn't try to teach; they should try to listen more. Listen to what your child tells you about the story and the characters. Ask them questions, let them explore the pictures and the words," he says.