Retired Hong Kong couple write the definitive Chinese recipe book

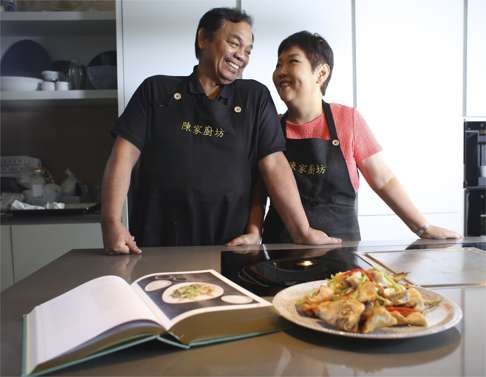

Chan Kei-lum, 75, and his wife, Diora, 65, have compiled 650 recipes from all of China’s major cuisines, as well as lesser known cuisines such as those of Xinjiang, Tibet and Inner Mongolia

When publisher Phaidon was looking for someone to write the China version of its cookery book series about national cuisines, it turned to a Hong Kong couple who have lived in China and have the culinary experience and pedigree to take on the daunting task.

But Chan Kei-lum, 75, and his wife, Diora Fong Hui-lan, 65, refused – twice – to take it on, pointing to the 12 months they were being given to compile all the recipes and background information for the book, and the fact they were busy with their own projects. While they have written a dozen cookbooks in Chinese, Phaidon’s China: The Cookbook, would be more difficult, as it had to be written in English.

WATCH the authors talk about compiling the recipes and cook a dish

However, with the encouragement of friends, they relented. The book, which will be launched globally on September 27, features more than 650 recipes from the eight great regional cuisines of China, and from Xinjiang, Tibet, Yunnan, Inner Mongolia and Taiwan. It joins the likes of The Nordic Cookbook, France: The Cookbook, The Lebanese Kitchen, and Peru: The Cookbook.

Chan is the son of Chan Mong-yan, a former chief editor of Hong Kong newspaper Sing Tao Daily, who was also a food columnist and cookbook author. The younger Chan learned early on how good food is made.

On the day we interviewed the Chans, it was their 39th wedding anniversary, and Fong says that in all that time, they have never argued.

They were introduced by friends at dim sum, when Chan was visiting Hong Kong from the United States where he was working. Chan thought she was too young then.

However, they kept in touch, and a few years later they married. Fong didn’t know how to cook but quickly started learning, and it was her highly developed palate that helped her become more than proficient in the kitchen.

The couple are well positioned to write China: The Cookbook because Chan spent a few years working for IBM China, while Fong had a business in structural steel engineering there. They also had another venture trying to help farmers grow organic vegetables and sheep in impoverished areas of China.

After they retired from the farming business and came back to Hong Kong, local publisher Wanli Books urged the Chans to write cookery books, which they started to do in 2009.

“When readers first buy our cookbooks, they buy one or two. And then after they made some dishes in there, they buy the entire set of cookbooks. We have never had a complaint about the recipes not working out for them,” Fong says.

For the Chans, China: The Cookbook, would have to be a large tome, as they insisted on covering all the regional cuisines, the culture of eating, and cooking techniques used in different parts of the country.

“Initially, Phaidon asked us to talk about the eight regional cooking styles plus a few others, and we said that doesn’t represent China, only parts of it,” says Chan. “So we decided to do some really remote areas of China like Xinjiang and Tibet, that people don’t have much knowledge about. Because if you want to write a book that has China on the front cover, we have to represent all of China. So we decided to cast our net wider than the eight major styles and cover all areas, including places like Taiwan and Mongolia.”

“Including 33 regions and sub-regions,” Fong adds, finishing her husband’s sentence. “You can see it’s a lot of hard work.”

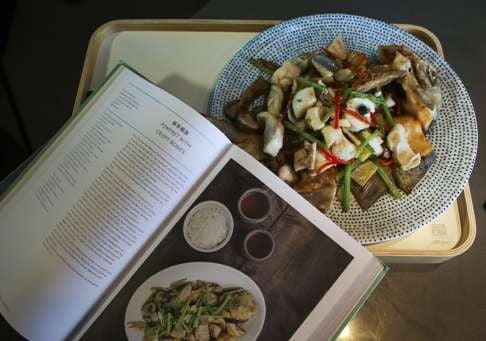

Chan says the actual selection of recipes was “painful”, as they wanted to reflect the diversity of China through the dishes, but some were weeded out if ingredients were not easily accessible, if the recipe couldn’t be made at home without special equipment, and if the taste was not acceptable for most people.

“Sometimes we refined the recipe to make it more tasty. Honestly speaking, in some regions, the taste isn’t very good for most people, but it is unique,” says Fong. “So we have to include it and refine it, or in some cases make it more simple for people to make at home. If it is complicated, no one will learn it.”

They tested every recipe a few times, making sure everything was correct, and 1,200 recipes were whittled down to the final 650.

“We ask our friends to come and take it. We tell them to come at 5pm and bring their own boxes,” says Chan with a laugh.

The hardest part for the couple was writing the extensive glossary, explaining practically all the ingredients and cooking methods in English.

“We had to explain each item so that people know what we are talking about and that they can find it. [Some of] the names are very misleading. The same food item can have several names. We had to try to standardise them or provide alternatives [because] when they go to a Chinese supermarket, people label things differently.

The writing part was not difficult, but naming ingredients was hard

“For example one of the sauces is made of fermented flour and yet if you go to the market, some labels say bean sauce, but there are no beans in it. So we spent a lot of time ironing out these problems and deciding what names we want to use for the ingredients. So the writing part was not difficult, but naming ingredients was hard.”

In the end Chan says they learned so much more about Chinese food, and they hope the book will make people outside China and Hong Kong understand that Chinese food isn’t like that found in Chinatowns.

“I would say it’s not just for home cooks but for professional cooks as well. Because professional cooks may know about certain regions like Cantonese or Sichuan but there are so many different areas they may not know about. This may be a good reference book for them as well as an introductory book for home cooks,” he says.

“This book will be useful for many Chinese people, too, because they are used to eating their own regional food, and hopefully this will be a chance for them to experiment with some food from other regions. Our objective is really to promote Chinese food to people around the world so that they may know more.”

The Chans will have a book signing in Hong Kong on September 17 at 3pm, at Joint Publishing, 1-1A, O’Brien Road, Wan Chai, tel: 2838 2081. The book can be ordered online at phaidon.com