World Wide Web dream are being lost in a maze of apps

Dreamers of a new world order being enabled by an egalitarian tool are becoming increasingly disillusioned by course the internet is taking

Tim Berners-Lee, the man who invented the World Wide Web nearly 24 years ago, believes the internet should maximise the sharing, perhaps caring, and certainly egalitarian principles realised by means of his invention.

At a recent talk, Berners-Lee cited the help the web can be to humanity as in the case of GeoEye, a company that shortly after Haiti's 2010 earthquake released satellite imagery of the devastated areas, with a licence that allowed people to use it.

Quickly, relief workers zoomed into it to build up a picture of which roads were blocked, which buildings damaged, where refugee camps were growing and when medical ships were reaching port.

"The site rapidly became the map to use on the ground if you were doing relief work," Berners-Lee said.

This sort of thing was what he hoped would be made possible after the birth of the web at Cern in Geneva in December 1990.

"It consisted of one website and one browser, which happened to be on the same computer," he recalls. The simple set-up demonstrated the profound concept that any person could share information with anyone else, anywhere. In this spirit, the web spread quickly from the grassroots up.

The web evolved into a powerful, ubiquitous tool because it was built on egalitarian principles and because thousands of individuals, universities and companies have worked, both independently and together as part of the World Wide Web Consortium [established by Berners-Lee so that stakeholders could collaborate to build a better web than any company could build by itself], to expand its capabilities based on those principles.

But, in spreading from the grass roots up, his invention arguably has lost many of the egalitarian principles Berners-Lee envisaged.

It has become less straightforwardly a force for good. Earlier this month, Charles Leadbeater, former policy adviser to the British Labour government and a champion of the web's potential to give power to deprived groups, published a report pointing to how the democratising potential of the internet has not been fulfilled.

Leadbeater said: "There is some sense in which the internet is in danger of not meeting its potential. The promise that was there in the mid-2000s, which was about collaborating to create better ways to do things."

That promise was something Leadbeater and others believed would be realised. In 2008, he published We-Think: Mass Innovation, Not Mass Production. At the same time in the United States, fellow web evangelist Clay Shirky published Here Comes Everybody: The Power of Organising Without Organisations.

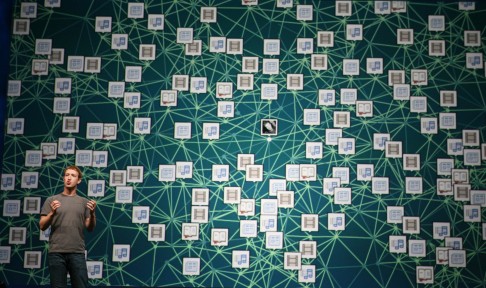

"We've had a year now in which the internet is regarded with a sort of weary cynicism by a lot of people, because Facebook are just locking you in, and others are using your data without you knowing it," Leadbeater said. "Some people are enthusiastic about that, because they get really good services and they love it, but quite a lot of other people are either quite doubtful or outright sceptical."

Sceptical is right. The web has increasingly facilitated the global spread of misogyny, the hate crime of revenge porn, corporate and state surveillance, bullying, racism and the life-ruining, time-wasting, digital servitude of deleting spam.

We can all draw up lists of how terrible online life is. But we are moaning about the internet, not the World Wide Web. They are two different things. Basically, the internet contains the web, which is a particular pipe inside the broader "internet" pipe.

"Web" tends to mean, "take these files and lay them out on a screen in a particular way", while "internet" means, "here's a file, do whatever you want with it". Indeed, Wired magazine, only four years ago, had an all-orange cover with four black words that read: "The Web is Dead."

It went on to argue that Berners-Lee's beautiful egalitarian vision had been supplanted by a customised, commercialised online paradise or hell (depending on your politics).

Internet thinker Chris Anderson wrote that increasingly we're abandoning the open, unfettered web for simpler, sleeker services online that work, and make lots of money for app creators.

If Anderson was to be believed, most internet users could measure out their days with app usage. Consider a typical day: you check your email on your iPad before getting out of bed, browse Facebook and Twitter over breakfast, listen to a podcast on your smartphone on the way to the office, at work have Skype conversations, and then go home to play games on your Xbox Live.

"You've spent the day on the internet, but not on the web," argued Anderson. "This is not a trivial distinction. Over the past few years, one of the most important shifts in the digital world has been the move from the wide-open web to semi-closed platforms that use the internet for transport but not the browser for display.

"It is driven primarily by the iPhone model of mobile computing. And it's the world that consumers are increasingly choosing, not because they're rejecting the idea of the web but because these dedicated platforms often just work better or fit better into their lives. The fact that it's easier for companies to make money on these platforms only cements the trend."

On that last point, it's worth considering the outcry that arose earlier this summer when an intriguing experiment performed on Facebook users went public.

It was revealed that, for a week in January 2012, hundreds of thousands of Facebook users had between 10 per cent and 90 per cent of the positive emotional content removed from their newsfeeds, which are the selection of friends' posts that appear on a home page when you log in.

The removals were part of a study by two US academics and a Facebook employee into what they called "emotional contagion via social networks".

The study found that reducing the number of emotionally positive posts in a newsfeed produced a significant fall in positive words they used in their own status updates and a slight increase in negative words.

Is that what Berners-Lee had in mind in Cern a quarter of a century ago?