City Under Siege: Hong Kong Is Drowning in Trash

If we don’t control our waste problem, our home will soon be buried in garbage—we throw out 15,000 tons every day.

Two IFC is Hong Kong’s second-tallest skyscraper. Its 88 floors stand at 412 meters tall, high above Victoria Harbour. But at the rate this city tosses out its waste, we could fill the building—in its entirety—with thrown-out plastic bottles, glass bottles and aluminum cans in just 162 days. It would take only half a year for Hongkongers to drown one of the city’s most iconic buildings in cast-off Coke cans and unwanted Tsingtaos.

Hong Kong has a trash problem.

The South East New Territories Landfill in Tseung Kwan O spans 100 hectares—that’s 435 times the size of Lan Kwai Fong. And it’s just not enough to keep up with the city’s waste.

Three years ago, the government’s Environment Bureau announced that the Tseung Kwan O landfill would reach capacity by 2015. The government is currently spending $2.1 million to expand the site by an extra 13 hectares, but it's just a stopgap measure.

Hong Kong produces some 15,000 tons of trash every day, the Environmental Protection Department’s (EPD) most recent statistics from 2014 show—and the city is anything but ready with a solution.

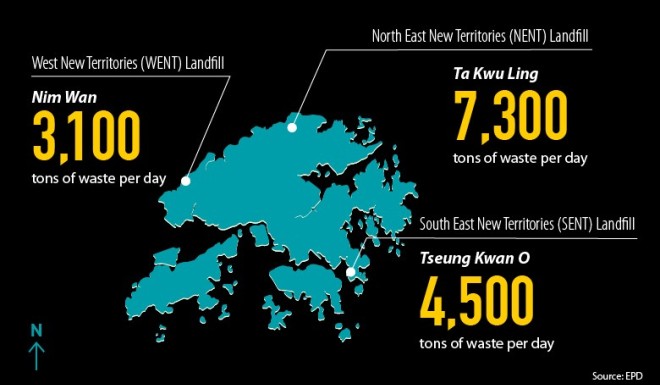

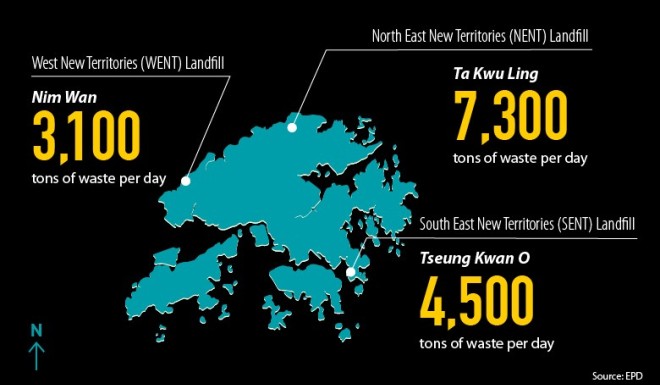

Along with the city’s two other landfills in the northeast and west of the New Territories, the government says the sites will last for “some years after 2018,” as it sinks money into expanding these enormous garbage dumps. The extension project in the northeast of the New Territories is costing Hong Kong $7.5 million for 70 hectares. The government already spent $38 million to explore the possibility of extending the landfill in the western New Territories.

Although the Environment Bureau rolled out a plan in February 2014 to reduce waste, ramp up recycling and look at ways to turn garbage into energy, efforts have been painfully slow to get off the ground. This year, the government decided to tackle Hong Kong’s waste problem the easiest and quickest way it could: by making the city’s landfills bigger.

“With recent funding… the landfills could cope with waste disposal up to the late 2020s,” says an EPD spokesperson. But, what happens after that? All three of Hong Kong’s landfills take up 271 hectares of our city’s space, over a quarter of Wan Chai district—and that number will be even bigger when the government’s extension projects go through. Hong Kong’s garbage mountain is going to be too big to ignore. And as for Lan Kwai Fong, Hong Kong’s three ever-growing landfills could fit the party spot 1,174 times over.

Solid Waste

The government has been long aware of the city’s trash problem, yet little action has been taken.

In 2004, the Legislative Council wrote in a paper that in 2003, the amount of construction materials that Hong Kong used—19,000 tons—could build a 26-story building the size of Happy Valley Racecourse.

Edwin Lau Che-feng is the founder and executive director of The Green Earth, Hong Kong’s newest green group. It advocates resource conservation through public education and awareness. He says that what Hong Kong throws out in one day—15,000 tons of solid waste—is equivalent to the weight of 10,000 cars.

“The government is slow to establish much needed legislation, such as charging for waste and regulating [waste] producer responsibility,” says Lau.

Last month, The Green Earth said that if the government keeps delaying dumping laws for major corporations, Hong Kong will end up throwing away 132 tons of plastic bottles every day. That amounts to about five million bottles every 24 hours, double what the city threw out 10 years ago.

The EPD’s 2014 statistics show that food accounts for about 40 percent of the city’s waste—food that’s taken straight to landfills.

Toxic Trash

When trash reaches a landfill after being compacted at a refuse transfer station, it is covered with soil and then a special type of plastic cover that prevents smells from coming out, and water from coming in. Landfill gas, a source of methane, is salvaged mostly for on-site energy production. Then leachate—the liquid that drains from a landfill—is collected and treated on-site before being pumped to sewage treatment facilities for further processing.

Turns out, this well-meaning measure can come at a human cost.

Jeffrey Hung Oi-shing, the manager of policy and research at environmental advocacy group Friends of the Earth, says that “although our landfills have systems in place to treat landfill gas and leachate, they are by no means safe.

“Landfill gas is composed primarily of methane gas, which is non-toxic but flammable and also a strong greenhouse gas. Leachate contains a mix of toxic compounds and heavy metals from passing through our trash and can be highly corrosive.”

The EPD acknowledges the grave toxic dangers of leachate in an official report.

Waste-to-Energy

In Singapore, which in 2014 threw out 8,338 tons of trash each day—about half of Hong Kong’s—rubbish is sent to incineration plants in order to generate energy.

Hong Kong is considering a similar type of waste-to-energy plant. Although still under judicial review, a project has been greenlit to build a waste incinerator on an artificial island, near Shek Kwu Chau on Cheung Chau. The EPD plans to roll out the first phase in 2023.

An EPD spokesperson says that the plant will treat 3,000 tons of waste per day, and supply 480 million kilowatt-hours of surplus electricity to the power grid each year—which is equivalent to the consumption of 100,000 households in Hong Kong per year. The EPD spokesperson also says that it will prevent the emission of some 440,000 tons of greenhouse gas every year.

Hung, however, calls the project an “end of the pipe” solution. For one, the plant may generate toxins, such as harmful dioxins—and the project doesn’t encourage the public to begin reducing waste at the source. Lau says that because this city in particular generates so much waste, the plant, which at most could cope with 20 percent of our trash every day, is less effective than cutting down on Hong Kong’s trash problem at the source.

Outside the Tseung Kwan O landfill, an inescapable haze stings the eyes and fills the air with the smell of rotting eggs. Trucks barrel through the roads, piled high with stinking refuse—plastic bottles and gardeners’ gloves litter the side of the road. The dump is just seven miles from the tranquil beaches of Sai Kung—and it’s creeping closer all the time.