Chinese chef smuggled to Gabon says he was 'left for dead'

Li Guangxian took off for central Africa in January this year, in hopes that a 7,500 yuan (HK$9,500) monthly salary promised for working as a “cook” would help put his daughter through university and provide a better life for his impoverished family back home in Anhui.

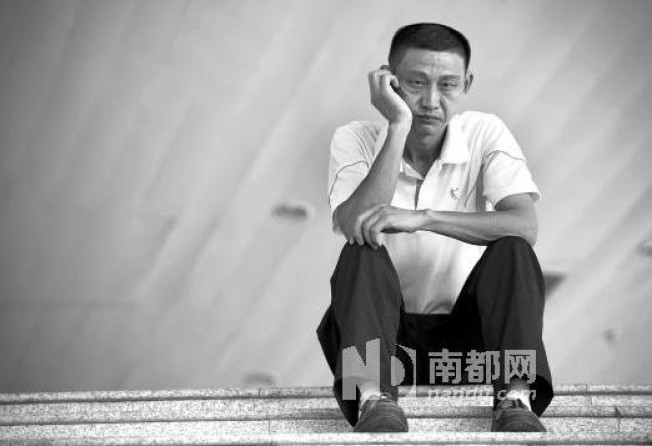

But in an interview with the Southern Metropolis Daily newspaper published on Tuesday, the 43-year-old Shenzhen-based chef recounted not a tale of gold and glory but a near death experience working at a timber mill deep in the mountainous jungles of Gabon.

Li is one of millions of migrant workers smuggled to Gabon and other African countries each year as Chinese companies rapidly expand their investments across the sub-continent. The National Development and Reform Commission estimated Chinese investment in 50 of the continent's 54 countries to have amounted to US$2.9 billion (HK$22.5 billion) last year, with an average annual growth rate of 50 per cent.

Forests cover about 85 per cent of the central African nation. The dense forestry is seen as a potentially vast economic asset up for grabs, especially by a resource-hungry China, whose operators have come to dominate the timber industry through a campaign of large-scale takeovers and acquisitions.

But the fruits of labour are rarely enjoyed by all. Li’s hellish ordeal in Gabon's capital Libreville lasted half a year. It was only in June that he and a few other Chinese workers were able to contact the Chinese embassy and go through a painstaking process to be put on a flight back to the mainland.

“The company withheld our wages for months. We requested to go home; they wouldn’t let us. When we were sick and wanted an advance to see a doctor; they would refuse,” Li told the newspaper, describing his nightmare at the remote timber plant, tucked away in thick jungle 15km from the nearest village. “I once told my wife I was prepared to die any day.”

Li was given a taste of what was to come right from day one after being smuggled to Gabon via Hong Kong, without a valid working visa. He was given two boarding passes by the Shenzhen-based Yifeng lumber company - one from Hong Kong to Jakarta (Indonesia does not require a visa from Chinese citizens) to get Li into Hong Kong, and another for Li's flight from Hong Kong to Libreville.

After hours of travel, Li finally reached his destination. Outside the mosquito-infested lumber mill of “Integrity International Timber Company”, where he was expected to work for the next two years, he witnessed dozens of knife-wielding workers protesting unpaid wages.

Li was given a metal freight container for a room, which he described as a “tin microwave” during the hottest hours of the day. Also provided to him was a metre-long machete for “self-defence” purposes – large snakes were known to be in the vicinity.

But giant pythons were not the scariest thing at the secluded camp. He was once held at knife-point by machete-wielding local labourers who forced Li to give them food from the kitchen.

Random police checks were frequent. Without official legal status in the country – the company claimed to have taken care of this – police conducted routine inspections and detain those without valid working permits. The company once had to bail him out of a dingy prison for 1,240 yuan.

Wages were withheld for months on end despite the fact he was forced to do other jobs such as maintenance and machinery repair. Instead of paying wages, the company gave the workers 600 yuan in “pocket money” at the end of each month – enough for “a few daily necessities and a [long-distance] phone call or two”, Li said.

He said he once caught a fever and had requested a loan to see a doctor. The company refused to pay up and instead gave him expired medication. It was at that point that Li requested to be sent home but was then threatened by a manager “not to stir trouble or else”.

“He told me that if someone died here in the mountains, no one would ever know,” Li said. Shortly after, they confiscated his company-issued machete out of fear he would participate in a violent uprising or strike.

Wang Shiping arrived at the camp in April and had a similar experience to Li. He described to the Daily how electricity was cut off at 9pm each night leaving the workers exposed to the dark, hot wilderness.

“Sometimes I would think to myself; it would actually be better to be a prisoner. At least prisoners are entitled to some form of personal safety. In Africa, we are left for dead,” he said.

Unable to make the company arrange for their return home and lacking the proper documents to do so themselves, Li and Wang called the Shenzhen police for help. They were advised to contact the Chinese embassy in Libreville.

After getting through to the embassy and waiting for weeks without a response, they were finally able to fly back with 13 other Chinese workers from Africa.

The Chinese mission in Libreville acknowledged they had been in contact with Li and Wang but said they received calls for help from migrant workers all the time and it was often difficult to intervene without actual powers of enforcement.

Li said he had attempted to confront Yifeng at their Shenzhen headquarters but was then told that they were “victims” too. They said Li could not take legal action because neither party had actually signed a legally-binding employment contract.