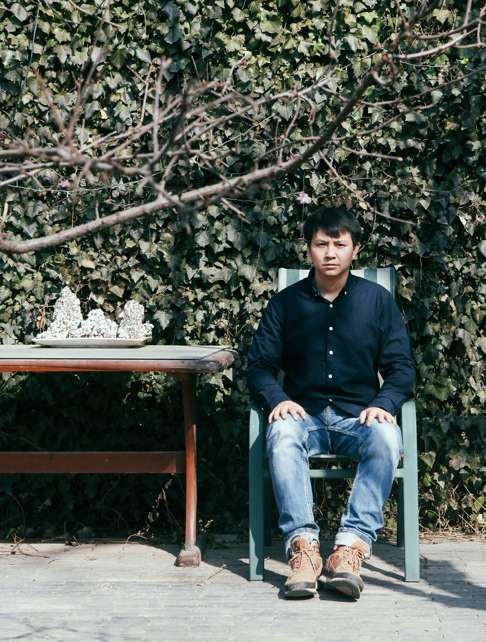

The Road taken: Controversial filmmaker Zhang Zanbo knows the true meaning of independence

In July 2008, Zhang Zanbo, then a teacher at the Beijing Film Academy, returned to his hometown to document the lives of residents in Suining county, Hunan, where the debris of rockets had fallen since the 1990s. That footage became Zhang’s first documentary, Falling from the Sky, which was later banned by mainland authorities. Zhang subsequently quit his teaching job to become an independent documentary filmmaker. In 2010, Zhang returned to Hunan where he documented the construction of an expressway over the next three years. His non-fiction book, The Road, was published in Chinese in November 2015 but was pulled off shelves and banned on the mainland this year for “unclear reasons,” Zhang said.

What is independent documentary, and how do you view the environment for it in China?

Different people have different understandings of “independent production”. I recently had a chat with a film critic who thinks dancing in shackles is also a type of “independence”. But I don’t think so. My version of independent production is a type of self-expression that speaks to my heart, without succumbing to ideological censorship, including self-censorship as well as market influence. It’s getting difficult to achieve that kind of freedom, particularly in this era flooded with philosophies of achieving quick success. The number of real independent productions is declining, and many creators have yielded to market pressure. Under such circumstances, it would be a luxury for me to talk about “environment.” It is, at most, a very small space that a tiny number of people still hold on to.

What made you decide to shoot The Road and spend three years documenting the construction of an expressway?

My childhood friend [Zhou] Binhe is a road construction worker. During our teenage years, I heard him telling many stories about people on road construction sites. This was the foremost reason for me to make a documentary about expressways. The second reason is more personal. I had just completed shooting Falling from the Sky, where I found my interest in documenting stories of the individual dignity and survival behind China’s fast development.

The biggest significance of this documentary is providing a fresh perspective of this rapidly developing era. This is also where the value of realistic documentaries lies. It was no problem for me to spend three years on this project because I had no job, and plenty of free time to kill. If not used to make this documentary, that period of time would have been wasted. “Time is money” never works for me.

Why is China’s poorer class attractive to you?

I may look somewhat like an artist or an intellectual, but I am part of the lower class. I shoot documentaries of them not because they are attractive but because I can clearly see my own life and fate though them.

In your book The Road, there is a sentence, ‘In some sense, the broad road I presented is also my own road’. Please elaborate.

To some extent, humans share the same kind of fate – others’ fates are our fates. Just as in my documentary Falling from the Sky,” the “sky”– the will of a nation’s rulers – not just descends upon the people living in the areas where the debris of rockets fall, but also looms above all our heads. The “road” in the documentary The Road is a kind of life that every one of us will pass by.

How much have you changed since you started making documentaries?

Not much has changed, except getting old and gaining a few pounds, because making documentaries requires lots of physical work. I had a small appetite for rice before. Now my appetite for rice has grown a lot, particularly in those years of living and shooting on construction sites. Fighting with construction workers for food made me enjoy my meals, and my weight therefore grew rapidly.

How do you support your independent production financially?

Earlier I relied on my savings from my previous job. After those savings had gone, I borrowed money, bummed meals from friends. … The good thing is I am a one-person team. I stick with – in fact I have no choice but to stick with – low-budget shooting. I have little desire for money – just enough to live on is fine. In this era, it’s not as difficult to survive as you would think.

Is there still only one person in your documentary studio?

Yes, just me. I’m not considering hiring another person. It’s difficult enough for me to continue doing what I am doing now.

What impact did it have on you when your book The Road was banned soon after its publication on the mainland?

Materially, my royalties shrank significantly. It was when the publishing house [Guangxi Normal University Press] was preparing for the second print of the book that they received notice that it would be pulled off the shelves. So the first print is out of print now and my plans to write two more books have been shelved as well. Spiritually, I have a deeper feeling of living in a country of mind control.

What film are you working on now?

I am shooting a documentary on refugee camps in Europe. It’s part of a project that a friend organised. The refugee issue in the Middle East is a heated topic that will have far-reaching influence globally. I am honoured to be part of it, and I am having an unforgettable experience that is different from shooting in China.

Why did you change your Weibo signature to “404 not found?”

The signature applies to my current situation. As you know, my documentaries and book have been deemed “404” (censored). I am planning to make an installation called “404 not found”. When it comes out, I think it will be censored as well. Isn’t that ridiculous? A piece of work called “404 not found” will eventually become “404 not found.” … The reason why I stick with Weibo and not WeChat [an instant messaging platform developed by Tencent] is that I regard Weibo as a platform for public speaking. I believe speaking in public is more valuable than whispering privately.

You studied drama at the Beijing Film Academy, so what do you think of China’s film market?

It’s a booming rubbish dump.