Want good books? Reward the writers, says head of China’s biggest online publisher

China Reading chief executive Wu Wenhui says it pays around 80 million yuan a month in copyright fees to authors

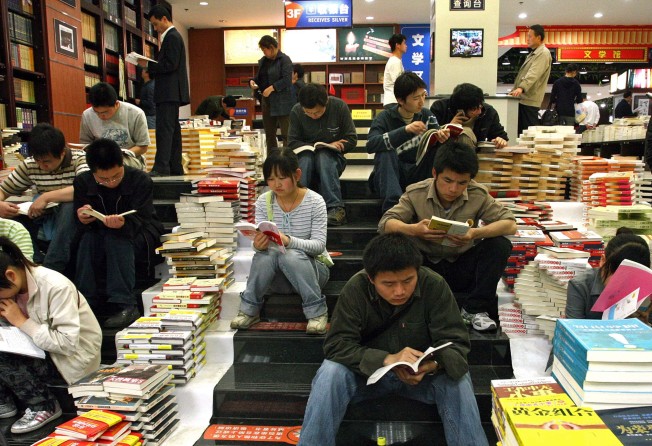

Forty per cent of mainlanders didn’t read a single book, in any format, last year, according to the Chinese Academy of Press and Publication. That compares unfavourably with the United States, where 16 per cent of people did not read a book in 2014, according to data from Statista.

But Wu Wenhui. the chief executive of China Reading, the country’s largest online publishing and e-book company, is optimistic about the sector’s prospects. even though its growth has been slow compared to other cultural sectors such as movies, computer games and video streaming platforms.

Wu, 39 and dubbed the godfather of China’s online literature by some Chinese media, talked to Jane Cai about the sector’s dynamics and challenges and his hopes for the future.

How did you become the helmsman of China’s leading online publishing platform?

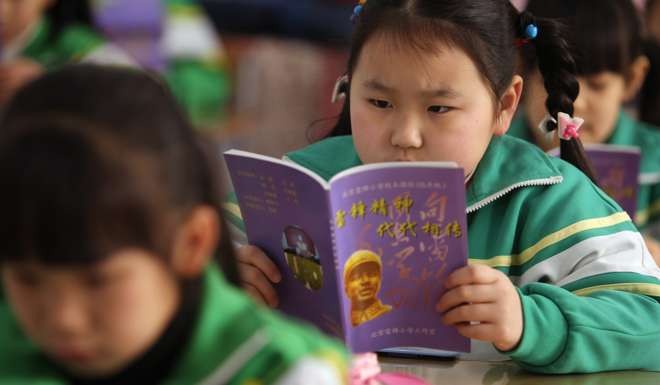

I majored in computer science in Peking University in the late ’90s, which made me among the first generation in China to embrace the internet. Reading had been a habit since I was a little boy, and the internet made content more accessible.

At that time, e-reading was free of charge and there were few online writers. Many authors wrote for Taiwanese publishers, where kung fu novels had a good market. After physical books were published, the stories were pasted in chat rooms on mainland websites and shared by online readers. Later, more readers came to imitate the lighthearted and intriguing narratives and publish what they wrote in chat rooms. When I graduated from the university in 2000, China’s first online reading platforms were emerging and I decided to set up an e-literature site, Qidian.com, with several friends in 2002.

Two years later, Qidian was merged with Shanda Cloudary, an e-publishing subsidiary of Shanghai-based games developer Shanda. In 2014, Shanda Cloudary was acquired by Tencent Literature, a subsidiary of Shenzhen-based internet giant Tencent Holdings. In March last year, China Reading, a child of the merger, was established and I was appointed chief executive.

You’ve been dubbed “the godfather of China’s online literature” by some media. What did you do to change the landscape of the industry?

I’m just one of the first movers. At Qidian, my team spearheaded the practice of getting writers paid, which generated huge debate. Our logic was simple: only when writers were rewarded would readers be able to get more quality content. But many opponents forecast that the model was doomed to fail as they thought readers were unwilling to pay. However, they were proven wrong.

We dedicated ourselves to promoting online novelists, who often went overlooked by traditional print publishers, and signed contracts with hundreds of them in the first years of Qidian. Also, we debuted an innovative system to let readers vote for their favourite books and writers and improved interactions between authors and their fans. Gradually, the model was accepted and followed by most of our peers.

How is your business faring?

At China Reading, about 70 per cent of our revenue is from e-reading via mobile apps and websites. The company owns nine e-reading platforms with a combined 600 million registered readers. They pay for VIP chapters after reading some parts free of charge. We share the income with authors. We had 4 million contract authors last year and more than 10,000 writers are joining the ranks annually. We pay around 80 million yuan (HK$90 million) a month in copyright fees to the authors. Popular writers could earn as much as 500,000 yuan a month.

Another major source of revenue is from the ownership of intellectual property (IP). IP has been a hot word in recent years as movies, TV shows and games adapted from popular online stories reaped huge market success. We had between 30 and 40 works of fiction adapted last year. This year, the number could even double.

The e-reading sector is growing steadily. The growth may not be as skyrocketing as movies or games, but the prospects are rosy. We have more and more young readers, born in the ’90s or younger, who would like to pay for content and authors they like. I think we can make a profit this year.

China is notorious for its poor protection of intellectual property. Is that a concern?

Piracy is indeed the biggest threat in the short term. There are numerous medium-sized and small websites which copy and paste original content at low cost. However, since this year, the Chinese government has been severely cracking down on piracy, prohibiting major search engine providers from linking to websites with pirated content. After that, the situation has somewhat improved.

What’s the biggest challenge in the long run?

Actually I’m more concerned about the mechanism for using quality IP. China has no counterparts of The Simpsons, Friends or 24, which can remain in vogue for more than a decade. Most of China’s original content has been badly distorted in the process of adaption by a few powerful film makers or game producers which have access to funds and film stars. They are short-sighted in seeking to earn quick money, showing no respect for IP or authors.

China’s film market is on the way to surpassing the US. Box office takings surged by nearly 50 per cent to 44 billion yuan last year. However, since this year, the growth has slowed markedly as audiences began to shun poor-quality stories. I hope this could help movie makers see the importance of good original content.

What kind of stories are most popular?

Most of our readers are between 15 and 40 years old, with the majority students and white-collar workers. Generally speaking, those about urban life, love stories and fantasies such as time travelling or tomb raiding are well received by Chinese readers.

We also have about 10 per cent of readers who are overseas Chinese. They like adventure fantasies which combine love affairs with wars and feature protagonists such as a teenager growing into a hero to save the world.

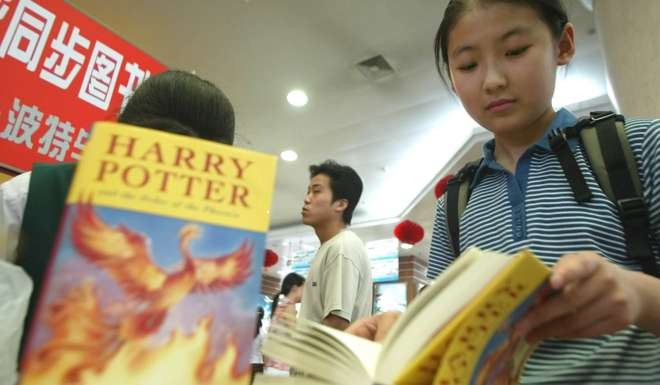

We also made some attempts to introduce translated books, such as the Chinese version of J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter. However, they were not well received, either because people had read pirated versions circulating online or the content was too serious for those looking for fun.

Chinese regulators have been tightening internet scrutiny. How are you affected?

We focus on novels which shun topics dealing with politics or violence, which are under strict scrutiny.

I think no one can deny that the internet has made the world more and more decentralised. Regulators should accept and respect people’s expression of opinions on the internet. They should learn to communicate with internet users more equitably and honestly.