Why China’s ‘parachute kids’ risk loneliness, alienation to study in the United States

Dreams of a better life and a second chance for pupils who are struggling in Chinese education system among factors encouraging parents to send their children abroad

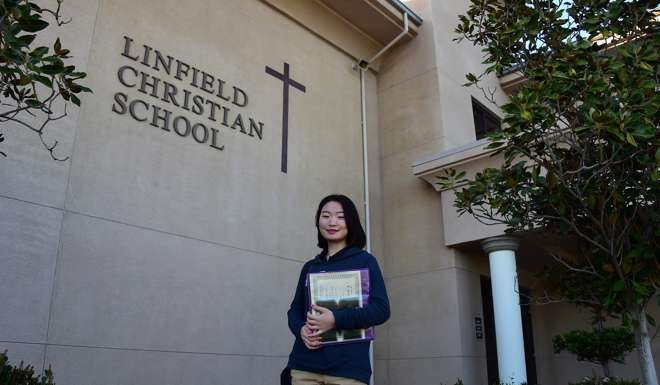

Before she came to the US for high school, Yuhan “Coco” Yang remembers wanting to “fly away” from her life in China where school began at the crack of dawn and lasted until the sky went dark.

She cried a lot her first few days at a private Catholic high school in Pomona in California, but at least she had freedom to be herself. She could go shopping, watch TV and meet friends at restaurants and tea houses in the Chinese-speaking suburbs of the San Gabriel Valley.

Her grades were decent, but she didn’t learn the lessons America was supposed to teach her until she was in prison.

“Life is a course where teachers and parents can’t help and where there is no choice but you walk by yourself, slowly,” Yang wrote in a letter from the California Institute for Women prison.

Now she is 19 and she has nine years left of her sentence. She doesn’t want to make excuses for what she did, she said in an interview. Being alone in the US put her in what she would only call a strange mindset. She expressed herself “impulsively and stupidly”.

“Obviously, I will never think of doing this again.”

Every year, more students like Yang arrive in American schools, dreaming of a future different from the one China allowed them.

Many of them consider themselves defectors from an unforgiving Chinese educational system in which, every year, nine million pupils compete for seven million university seats. About a million of those who are rejected attend colleges overseas. In 2015, 300,000 of those came to the US.

A growing number of students, however, are leaving the Chinese system even earlier. In the past decade, the number of Chinese pupils in US high schools rose from 1,200 to 52,000. More than a quarter of these students — called “parachute kids” because they often come here without their families — land in California.

Globalisation and rapid wealth creation have put two Chinese traditional values at odds: family and education.

More and more families are choosing to split themselves apart, said Yuying Tsong, a professor at California State University, Fullerton, who is conducting a study on parachute kids.

“It’s this mindset of ‘I’m going to do everything and sacrifice for you,’ ” Tsong said. “Even if it means we must be separated.”

At Bill Zhou’s home in Rowland Heights, the clock strikes 7pm, trick-or-treaters are ringing the doorbell, and his 17-year-old home-stay student, who spoke on the condition he be called only by his surname Hsu, has still not come home from school.

Zhou is getting anxious. He taps out a text. Finally, he calls, pacing as he listens to the ringtone.

Most Chinese minors studying in the US live in homestay arrangements like this: an acquaintance, friend or stranger from the internet who agrees to feed, house and care for the students for about US1,000 a month. They form a huge, unregulated industry of parental surrogacy that depends largely on the good intentions of host families to ensure the students’ safety and health.

Parachute kids, separated from their family and culture at a formative age, are more susceptible to isolation, aggression, anxiety, depression and suicide, Tsong said. It’s difficult for homestay families and schools to reproduce the support pupils might have had in China. And the pressure of making good on their parents’ investment doesn’t help.

“The parents sacrifice a lot, but they may not remember that the child is also sacrificing a lot,” Tsong said.

Some kids lose their way, said Hsingfang Chang, a Pasadena psychologist who specialises in working with Chinese families that send their kids to study in America.

“Teenagers need to connect and belong to their own community,” Chang said.” They look for popular girls, boys or cliques to connect to. And when they don’t have their family around, this need becomes even more strong.”

They don’t know if the school is good. They don’t know if the homestay is good. But everyone else is doing it so they do it too. It’s reckless

A few minutes after 8 pm, Hsu arrives. In his room, he opens his binder to the day’s homework, a vocabulary worksheet with words like “reasonable”, “austere” and “genre”.

Hsu is a shy 17-year-old. He’s skinny, but he doesn’t plan to stay that way. A giant jar of protein powder sits on the shelf above his desk next to a picture of his parents, with whom he texts every day.

His father, an executive at a Chinese telecom company, suggested studying in the US and Hsu agreed.

Hsu wants to be a dentist. Upon further questioning, he admits that it was his mother’s idea, but he doesn’t have a problem with it.

Someday he wants to go to the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and that was definitely his call. He’s a huge fan of NBA star and UCLA alumni Russell Westbrook.

So far, his new life in America consists of school, basketball and computer games. He has been in the country only three months and someone has already shouted at him to go back to his country. In the mornings at Southlands Christian School, he lowers his head in prayer. Nearly half of Chinese parachute kids attended private Christian high schools in 2015 — public schools don’t accept many international students and private schools tend to be religious — and although Hsu is not religious, he follows the rules.

America is growing on him. His English is still weak, but he knows all the lyrics to Eminem and Rihanna’s Love the Way You Lie. He feels more relaxed. His grades have improved, As in everything except some Bs in gym and maths.

“I was below average in China,” Hsu said. “Here I am above average.”

Zhou takes pride in Hsu’s success. He keeps a screenshot of Hsu’s recent report card on his phone and proudly displays it to whoever is interested.

Both of them are from Shenzhen and Zhou’s wife makes local dishes for dinner each night. Zhou wants to make Hsu feel welcome, but he knows there are things a fatherly pat on the back cannot accomplish.

Parents of children as young as six have responded to his homestay advertisement, although he won’t take students that young and he is worried that many of them don’t know enough about the situations their children are entering. Most use brokers and agents to arrange their children’s education and housing.

“They don’t know if the school is good. They don’t know if the home stay is good. But everyone else is doing it so they do it too,” Zhou said. “It’s reckless.”

In Wuhan in Hubei province in central China, Allen Qu’s grades were average and the schools group pupils by performance as early as middle school.

So Qu was placed on a track for average students, a path that would lead to an average university, followed by an average job and an average future.

So his parents told him he was going to America and he agreed. They dropped him off at a boarding school in San Marino and then went on vacation to New York.

But studies show that rates of employment and compensation for students returning with American degrees in China are lower than those of domestic graduates. In the end, most families choose an American education for the status that it confers on the family, said Dennis Yang, a researcher who wrote a book about his experiences embedding with several Chinese families deciding to send their children abroad.

“They all expect their children to be the valedictorian. If they’re unable to get that, going to an American university is a way to compensate,” Yang said.

Qu is 17 and he is not sure what he wants to do with his life. But at Southwestern Academy, he has friends, a better grade in maths and much less homework.

The parents sacrifice a lot, but they may not remember that the child is also sacrificing a lot

He chats on video with his parents a few times a month. His mother misses him terribly. His father, who runs a construction materials business, is a little more distant, according to Qu. The Lunar New Year holiday is the loneliest time, he added.

“They don’t really visit,” Qu said. Then he added, as if apologising: “They come if they have time.”

The boarding school, in the centre of a residential neighbourhood in San Marino, struggles to engage overseas parents, said Robin Jarchow, a dean.

The school’s student body is now about 86 per cent international students and more than half of them are from China. International parents are rarely in town and there is not much communication with the staff. The school assigns “dorm parents” to watch over each group of children and faculty members sit at every lunch table.

For some pupils, separation from their parents allows them to grow in ways that life in China would have denied.

On a recent weekday at the school, in an art room with a 3-D printer, a Chinese international student aspiring to a career as a product designer sketches plans for a wallet that functions as a phone charger. Next door, some Chinese students gather for band practice.

A pink-haired girl from Shanghai taps out a tune on the piano, working the pedal with gold Vans shoes, while her friend picks up a guitar.

The drummer, another Chinese student, sweeps dyed blue hair from her face and starts the beat. Another Chinese student takes up the mic

The tune emerges, shaky, but recognizable: Destiny’s Child’s Say My Name.

On her daughter’s last day in China, after all the bags were packed and all the school supplies were purchased, Aimee Guo had just one thing left to do, the most important thing.

She drove her daughter, Olivia, to a hair salon in Hangzhou.

Chinese belief holds that a haircut can bring good luck, symbolising transition, a way to shake off the past and leave all the bad luck on the ground next to the old hair.

The haircut was their ritual before every new school semester. But this one was different, Guo said. The past they were leaving behind was a happy childhood in a house full of love in Hangzhou. The future wasn’t just a new semester, but a new life as a long-distance mother to a daughter an ocean away.

There was lots of crying. But Olivia had been dreaming of this since she was a kid.

While many of the students arriving in the US are average or poor students, Olivia was at the top of her class, her mother says. Most students arrive without much English ability, but Olivia, 17, and speaks fluent English.

And although many pupils are forced to come to America by their parents, Olivia had to persuade her parents. Once her grades improved enough, they let her go.

Olivia cried a lot her first few weeks in America. She couldn’t get used to eating her homestay family’s Mexican food all the time, or how close Americans stood to you when they talked.

But she made friends quickly and began to excel at Fairmont Prep Academy, a private school in Anaheim. Her host family was patient and affectionate.

She became more patient and more mature and her grades reflected that. She recently took the SAT test for college admission for the first time over the summer, and it didn’t go well — she described her score as “bad, bad, bad. Like super bad”.

But in a few days, she will get something she would have never had in China — a second chance. She’ll take the SAT again and get another opportunity to impress colleges and universities, another shot at achieving her dreams.