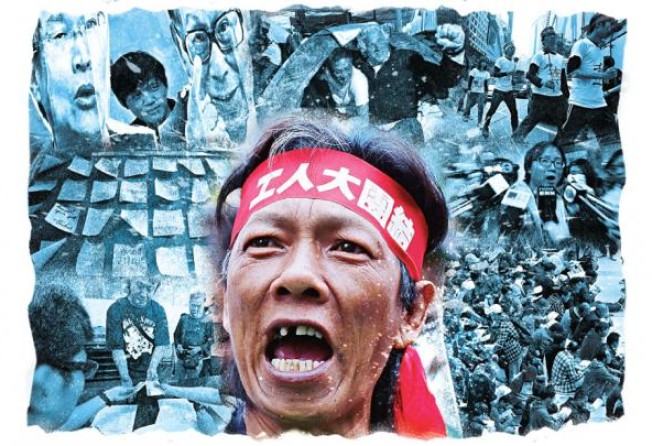

Labour unions hindered by lack of collective bargaining law

While the dockers' strike has shown the determination of some unionists, government's cosiness with bosses means scales are tipped against them

The strike by Hong Kong dockers has put labour unions in the spotlight after years spent in the shadows.

Yet union membership in the city remains low. Labour Department figures show that unions and staff associations claimed total membership of just over 800,000, representing 23per cent of the workforce.

It's a far lower participation rate than in other Asian countries, and a far cry from 1967 when strikes in the shipping, taxi, textile and cement industries escalated into the biggest outbreak of unrest in the city's history.

That led to a change in the picture for trade unionism. According to a 2005 report by the think tank Civic Exchange, the riots and other protests, along with pressure from British labour unions, led to implementation of the Employment Ordinance in 1968, offering more rights for employees. However, academics and unionists say workers are still seeing few benefits, their cause hindered by the city's economic and social structure.

Even in the strike by dockers, who claim their wages have not risen in 15 years, employers have been reluctant to come to the bargaining table.

Strike organisers attribute this reluctance to the lack of collective bargaining law in Hong Kong, while an expert on labour issues says the political influence of businessmen has made it difficult to pass labour laws.

Dr Chung Kim-wah, an assistant professor at Polytechnic University's department of applied social sciences, cites the fact the business elite dominated the 1,200-strong committee that elected Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying as an example of how the city was inclined towards the commercial sector.

While many industries can select representatives to join the committee, he says, just 10 per cent of its membership represent the labour and social welfare sectors. The picture is similar in the Legislative Council, on which 35 of the 70 lawmakers represent functional constituencies, most of which are dominated by big business.

"The government needs to gain support from the commercial sector, so it's reluctant to push forward laws against the businessmen's will," Chung says.

Chung says that although a minimum wage law was passed in 2010 and the Mandatory Provident Fund, under which employers and employees contribute to support the worker in his later years, was created in 1995, labour rights have been slow to improve.

Hong Kong scrapped plans to introduce a collective bargaining law in 1997. The law would have required workers to negotiate with unions and regulated what tactics each side could employ in a labour dispute. The government is unlikely to reintroduce it.

Plans for standard working hours and mandatory paternity leave legislation also remain on the drawing board. According to a government study last year, Hong Kong employees worked an average of 47 hours per week in 2011, and 23.4 per cent worked overtime, the longest working hours in the developed world.

Chung says the labour rights situation in Hong Kong is similar to that in Singapore, but lags behind the likes of South Korea and European countries, which give unions more power and have more comprehensive protection for workers.

Mung Siu-tat, chief executive of the pro-democracy Confederation of Trade Unions, which represents 170,000 workers and is supporting the strike, says the dispute at the terminal reflects the general situation in Hong Kong. He says workers' wages in have been cut multiple times and are lower than in 1997, while living expenses have increased.

He attributes the problem to the trend of contracting out the employment of lower-skilled workers to subcontractors. "It all started with the government, who outsourced security guard and cleaning worker jobs in the 1990s," Mung says.

Mung estimates that up to 50,000 people work for the government or public organisations through contractors. Rather than seeing a minimum wage as an improvement, Mung says it is an attempt to rectify problems caused by contracting out work. The statutory minimum wage of HK$28 per hour will increase to HK$30 next month.

Mung says the "small-circle" election of the chief executive could lead to collusion, and is not good for the development of workers' rights.

Lawmaker Wong Kwok-kin, of the pro-Beijing Federation of Trade Unions, says the economic structure of Hong Kong had contributed to a decline in salaries for some workers.

There is a lack of variety in the Hong Kong economy. There are not many jobs in industries other than finance and retailing, so it's difficult for workers to ask for better welfare

"There is a lack of variety in the Hong Kong economy," he says. "There are not many jobs in industries other than finance and retailing, so it's difficult for workers to ask for better welfare."

Both Mung and Wong recognise that many union members in Hong Kong are more interested in discounts and courses offered by unions, rather than their bargaining power.

"Many FTU members joined us because they wanted to attend our courses," Wong says. "It's difficult to make workers in Hong Kong more conscientious about their rights. It's about culture."

He says many workers are newcomers from the mainland, whose background makes them reluctant to voice demands.

While the percentage of Hong Kong workers in unions is similar to the average in Europe and far higher than the United States, Chung says the absence of laws protecting unions could be putting potential members off.

The Employment Ordinance stipulates that every employee should have the right to join a trade union, and employers cannot dismiss, penalise or discriminate against any employees for exercising their rights. Any employer contravening the law could face a fine of HK$100,000.

But Chung says some employers use other reasons to lay off union members, leaving the Labour Department with little scope to act. In other countries, he says, an investigation could be launched if union members were sacked, leading to potentially grave consequences for any employers breaking the law.

"And with collective bargaining, the employers would know it's useless to lay off a union member, as they are still obliged by law to talk to the union," he adds.

Mung agrees that unions in Hong Kong lack leverage in negotiations. Of the 80 smaller unions operating under the CTU's banner, only two - the Cathay Pacific Airways Flight Attendants Union and Hong Kong Aircrew Officers Association, which represents Cathay pilots - had signed collective bargaining agreements with an employer.

"The number of union members in Hong Kong does not reflect unions' power at all," Mung says.

Chung says the conflicting political views of the CTU and the FTU had hindered co-operation. Most recently, the FTU said it had largely stayed out of the dockers' strike because it was organised by the CTU.

When the bar benders went on strike with the help of the CTU in 2007, the FTU's participation was also minimal.

Wong denies that the FTU always comes out on the side of the government. "On some issues, we are more likely to support the government. But it's not that we're always on its side," he says.

Money also separates the two union groups, Chung says.

"Traditionally, the leftist FTU receives more donations," he says. "But for the dockers' strike, organised by the CTU, it wouldn't have been possible without public donations."

Chung points out that the pro-democracy CTU has been gaining momentum in the past 10 years, but stresses that the pro-business political structure in Hong Kong will make further progress a challenge.