Diamond hunting on the Atlantic Ocean floor with giant vacuum-like hoses

Last year, mining companies extracted US$600 million worth of diamonds off the Namibian coast as the output of existing onshore mines declines

Deep beneath a frigid stretch of the Atlantic Ocean, some of the world’s most valuable diamonds are scattered like lost change. The discovery of such gems has sparked a revolution in one of the world’s most storied industries, sending mining companies on a race for precious stones buried just under the seafloor.

For more than a century, open-pit diamond mines have been some of the most valuable real estate on Earth, with swaths of southern Africa producing billions of dollars of wealth. But those mines are gradually being exhausted. Experts predict that the output of existing onshore mines will decline by around 2 per cent annually in coming years. By 2050, production might cease.

Now, some of the first “floating mines” could offer hope for the world’s most mythologised gemstone, and extend a lifeline to countries like Namibia whose economies depend on diamonds. Last year, mining companies extracted US$600 million worth of diamonds off the Namibian coast, sucking them up in giant vacuum-like hoses.

“As [Namibia’s] land-based mines enter their twilight years, it’s very important for us and for Namibia that we have long-term mining prospects,” said Bruce Cleaver, the chief executive of De Beers.

But as companies weigh the prospect of more offshore operations, environmentalists have raised concerns about the damage that could be inflicted on the seafloor.

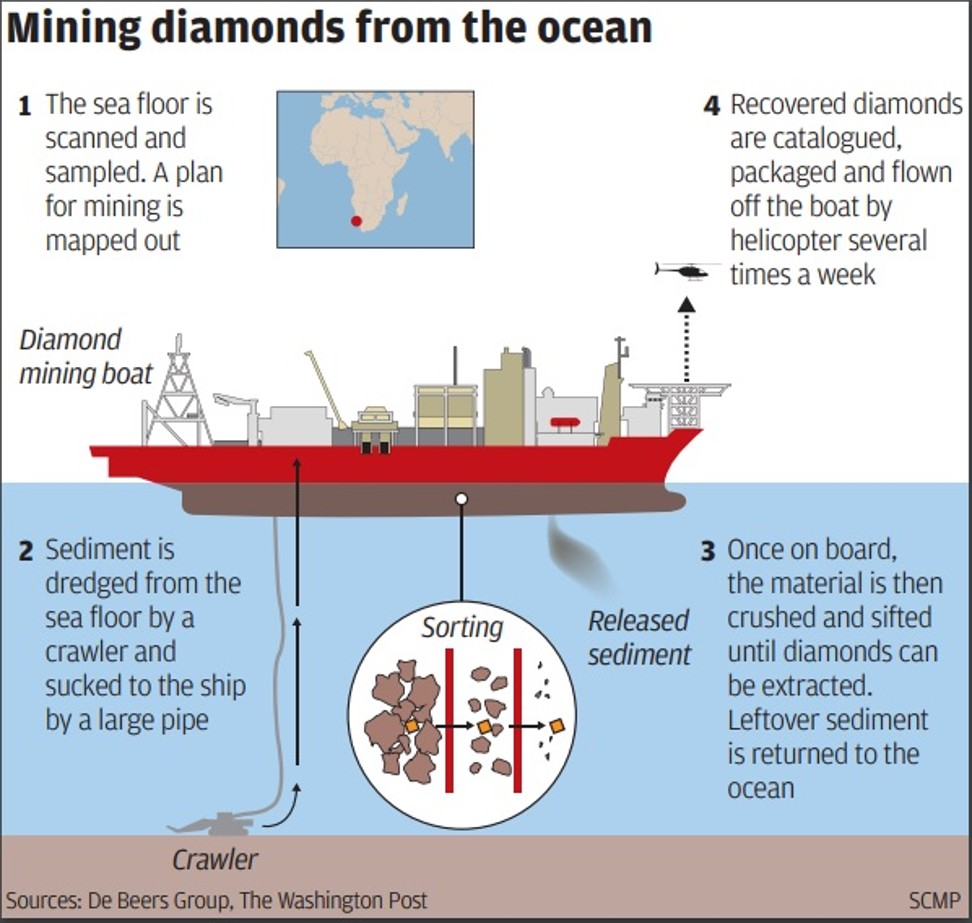

From above, the mining vessels look like oil rigs, 90-metre-long ships with helicopter landing platforms, dredging equipment and industrial metal pilings. On a recent day, a family of seals swam off one of them, as the machines hummed and sediment was sucked on board through a 170-metre hose to be sorted. It might be the world’s most complex commercial mining endeavour.

Diamonds are formed when carbon is subjected to high temperatures and pressure deep underground. Some were hurled toward the surface millions of years ago in volcanic eruptions.

In recent decades, geologists realised that because diamonds could be found in Namibia’s Orange River, there was a good chance they could also be detected at sea, swept there by the current. As it turned out, the underwater gems were among the world’s most valuable stones – with far greater clarity than diamonds mined on land.

De Beers, which historically dominated global diamond production, purchased mining rights to more than 7,700 square kilometres of the Namibian seafloor in 1991. So far, it has explored only 3 per cent of that area.

The technology to extract the underwater diamonds took years to develop. Only recently has the firm been able to efficiently scavenge the sea for diamonds. Underwater gems only represent about 13 per cent of the value of diamonds De Beers mines onshore each year, but more countries are pushing for exploration to begin along their coastlines.

At the unveiling last month of the SS Nujoma, a giant exploration vessel, former Namibian president Sam Nujoma smashed a bottle of champagne over the hull, surrounded by signs that read: “The future of marine diamond mining is here, and it’s Namibian.”

Watch: marine mining with the SS Nujoma

Last year, the world spent US$80 billion on diamond jewellery, more than half of it in the United States, an all-time high. Demand in emerging economies such as China and India is also expected to increase.

Those trends – diminishing supply and rising demand – made Namibia’s offshore deposits all the more important. In the 1990s, De Beers sent its first commercial vessels into the Atlantic in search of diamonds. Now, more than 90 per cent of Namibia’s diamond-related revenue comes from offshore finds.

These days, the company uses drones to fly over vast stretches of the ocean, looking for areas that might be worth exploring. Then it sends vessels like the Mafuta to dredge the most promising areas. Most of the diamonds are close to the surface, De Beers said, so it does not go deeper than six feet beneath the seafloor.

The mining vessels combine technology from oil rigs, dredging ships and even canneries to do their work. A remote control, tractor-like crawler moves slowly along the surface of the seafloor, directing a hose that sucks up tonnes of sediment every hour.

The sediment is then passed through a series of machines that cull material first by size and then, using X-ray technology, by geological composition. Diamonds make their way down five floors of conveyor belts and machines into a metal container that looks like a soup can.

Diamond mining contributes roughly one-tenth of Namibia’s gross domestic product, and its offshore contract with De Beers is a 50-50 partnership with the government. But while the soaring revenue has made some Namibians rich, this remains the world’s third-most unequal country, according to the World Bank, with millions of people unaided by the diamond rush.

Although Namibia is considered the easiest place to extract offshore diamonds, mining executives are not ruling out exploring other stretches of ocean. Marine mining has also taken place off the coast of South Africa, though it has proven less lucrative.

But environmental groups have raised concerns about the offshore mining operations, which spew the sediment back into the ocean after it is processed for diamonds. Companies also plan to begin mining offshore for gold in coming years, with one commercial operation scheduled to launch in 2018 off Papua New Guinea.

“My concern with this and all deep-sea mining is that we just don’t know much about the deep sea at all,” said Emily Jeffers, an attorney with the Centre for Biological Diversity, a US non-profit organisation. “The worry is that we are going to irreparably harm this environment and these species before we discover them.”

De Beers said its offshore operations do not cause significant ecological damage, as sediment is returned to the sea and eventually resettles. The company said it employed ecologists who monitor the environment where they have mined to make sure it is recovering.