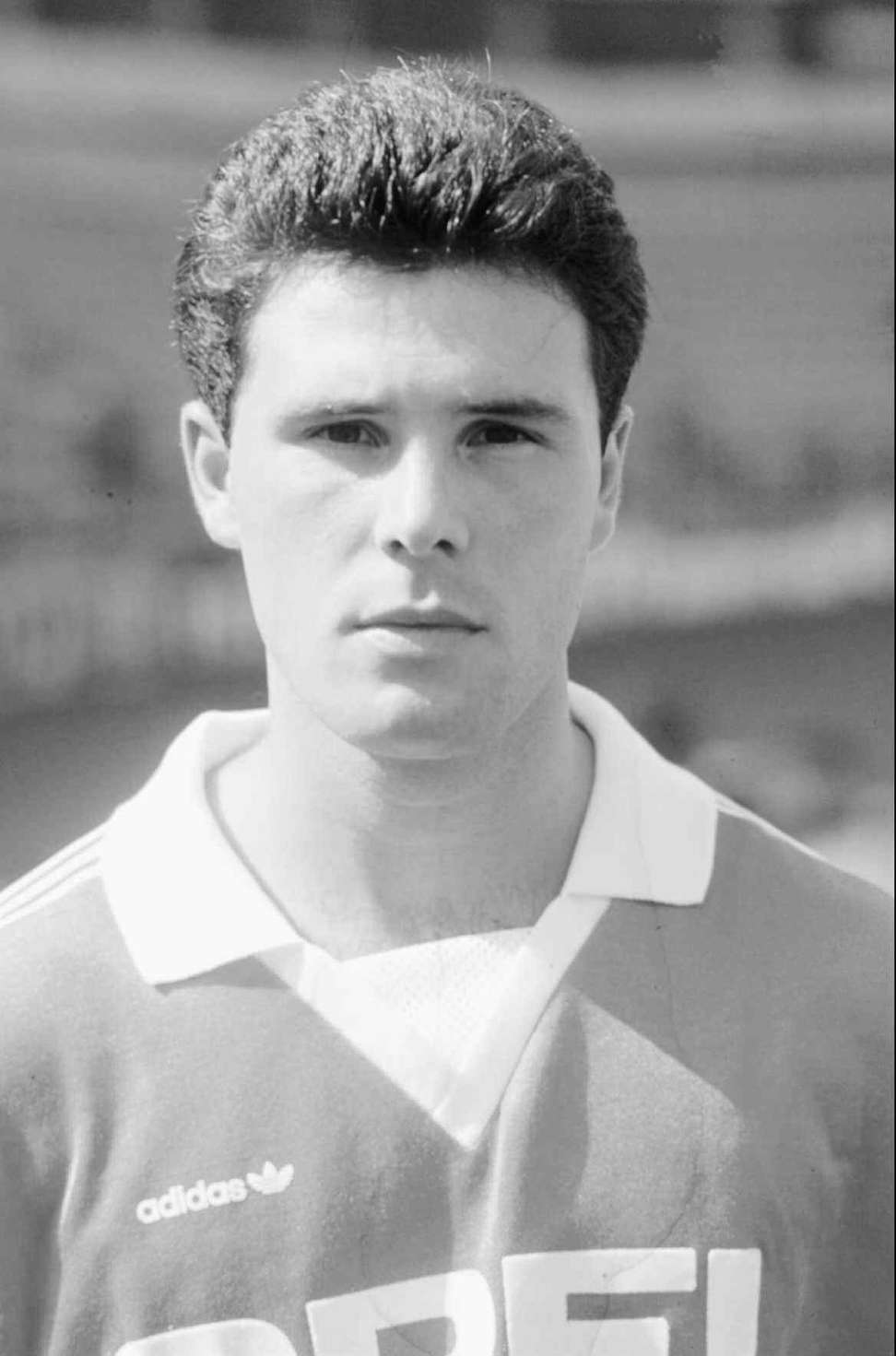

Player behind the Bosman rule should be booked for his part in Brexit

Former RC Liege player has had more of an impact on European club football than any other player, including Cristiano Ronaldo and Lionel Messi

The finger-jabbing over who caused the mother of all divorces has begun in earnest among so-called Remoaners – those who voted to remain in the European Union but lost in last year’s Brexit referendum.

British Prime Minister Theresa May dispatched a courtier to Brussels this week with the formal letter to start the two-year leaving process.

The phoney naming and blaming game is over. But where to start, and who and what to blame? The culprits are many, and that’s not counting the 17.4 million who voted out.

The witch-hunt could begin in the fair Brussels city of Liege, because that’s where the Remoaners should find Jean-Marc Bosman.

The former RFC Liege player has had more of an impact on European club football than any other player – and that includes Cristiano Ronaldo and Lionel Messi.

And his crusade to change employment laws in football exposed the many flaws in the EU’s core free movement of labour rule.

In 1990, when his contract had lapsed, Bosman sued his Belgian club for not letting him go. Liege offered the mediocre midfielder a new contract worth four times less than his previous deal.

Yet when rival Dunkirk FC offered to buy him, Liege demanded four times the price they had paid for the player.

In other words, they believed he had become four times better if he wanted to leave and four times worse if he wanted to sign again for them.

With only this lose-lose deal on the table, he not only sued Liege but also the Belgian FA, Uefa and Fifa for breaching the 1957 Treaty of Rome, which allows freedom of movement within the European Community, now the European Union.

The case went to the European Court of Justice in 1995 and the Luxembourg beaks ruled that clubs cannot demand transfer fees when contracts have expired.

Before 1995, an out-of-contract player could not simply leave a club. A free transfer had to be granted or another club’s fee accepted. A player could not run down a contract to depart for nothing, and certainly not sign a pre-contract agreement with a rival if they had less than six months remaining on an existing deal.

The court also decided that quotas restricting the number of EU foreigners in European club teams had to go, too.

European Union cheerleaders said this was the power of the gold star-spangled club in action, and trade unions and human rights groupies, too, rejoiced. This was, they declared, a triumph of European law standing up to the continent’s oppressors of le workers.

Football agents were also cock-a-hoop. Bosman’s victory changed football beyond all recognition. Power swung from clubs to players – and therefore to agents.

His name entered the football and legal lexicon. “On a Bosman” and “a Bosman deal” became the standard haggling auction talk during transfer windows.

And though the foreign quota may have benefited those playing in Europe, many English clubs have since witnessed a significant cultural shift as the movement of European players and buckets of cash freely flowed across the English Channel.

Today, the UK Professional Footballs’ Association estimates the chances of an English player signing for a Premier League Club at 16 and making the first team by 21 at just 17 per cent. And of the 600 who do sign, only 100 would be left five years later.

And there’s a slew of other reasons for fans to detest what has happened as a result of the Bosman ruling, among them sky-high salaries and transfer fees for star players, a handful of elite clubs who now tower above the rest, and club teams composed entirely of non-nationals.

For every fan that believes the Bosman law and the EU have brought better players and a higher standard of entertainment, there is one – if not more – who feels that football has been taken away from them.

So when the chance arose last June to vent their anger and strike back against the evil forces of globalisation, liberalisation and commercialisation, they duly did.

So Remainers have a legitimate claim to blame Bosman and EU law for Brexit.

Publishers should also consider a rush to Liege and seek out Bosman. He didn’t have much of a career after his single-handed revolution. He stopped playing in his 20s, was sentenced to jail for assault and has had periods of unemployment.

He’d surely sign any contract for a book deal. Football and the EU: my part in their downfall would be a best-seller among both camps.