How Hong Kong land policies help fuel city’s ever-rising property prices

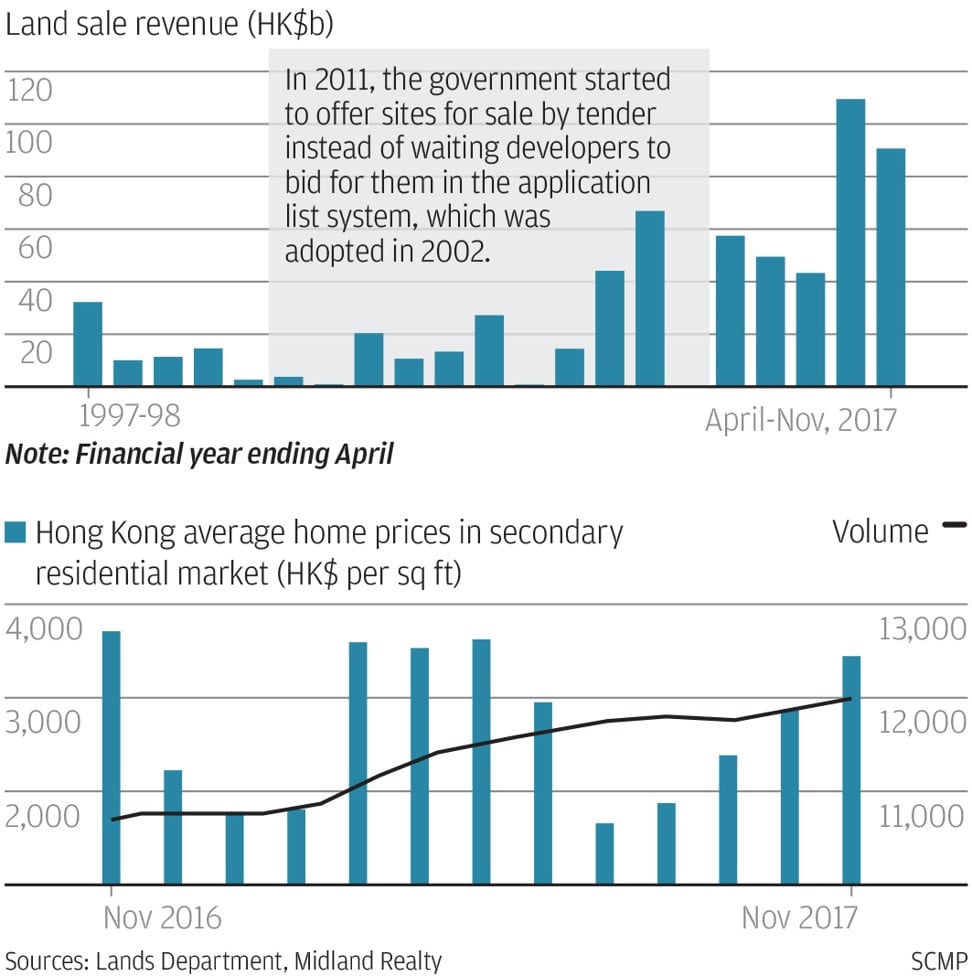

Hong Kong’s government is on track to post a record haul from selling land to housing and commercial developers in its fiscal year ending March 2018, bolstered by ever-rising prices in the world’s most expensive urban centre.

For the eight months ended November, and with another quarter to go before the close of its fiscal year, the government received HK$90.68 billion from selling 12 pieces of residential and commercial land, a mere HK$19 billion short of the 2016 record of HK$109.5 billion .

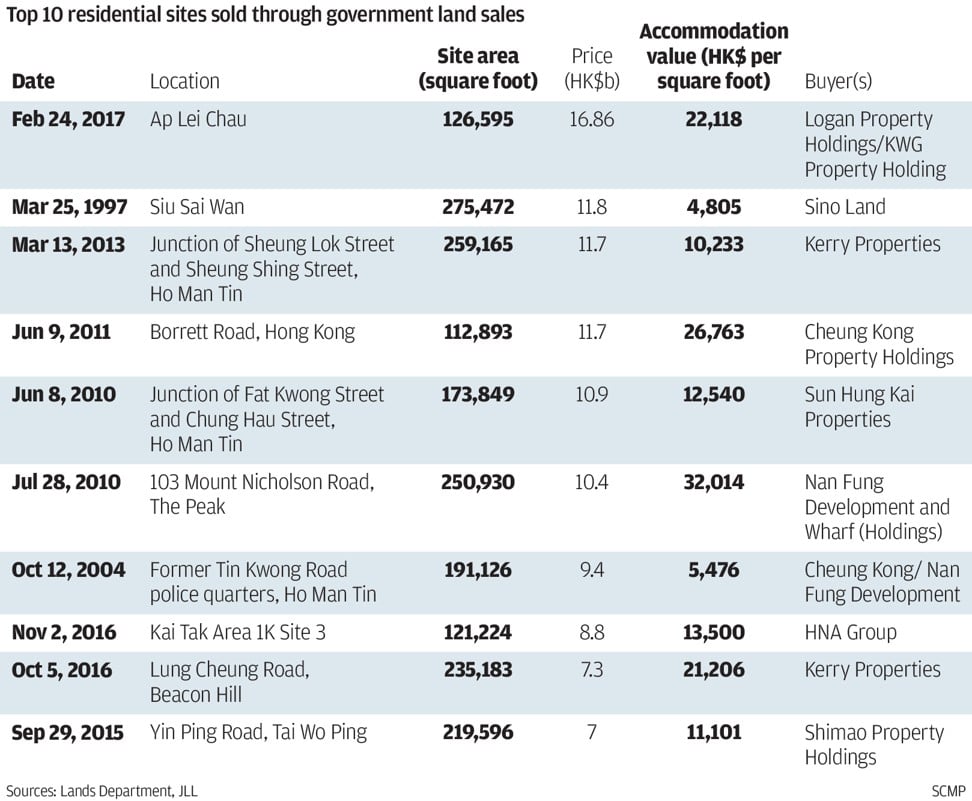

That translates in the real world to jaw-dropping prices for land, which have added substantially to developers’ costs, eroding their bottom line. The result is a property industry of ever-higher prices, as builders pass their costs to homebuyers to preserve their profit margin.

One option to cut the Gordian Knot is to try a different approach in making land available for development, some builders and planners say. Instead of selling land to the highest bidder, award the plot based on a broader set of criteria such as the overall economic impact, job creation opportunities, or even cultural benefits to the community, they said.

“Although Hong Kong government has generated huge land sale revenue, money will be used up one day,” said Oval Partnership’s Law. “But a well planned property development could offer long term economic or cultural benefit to a city for the next 50 years.”

Not so fast, said critics of this approach. Highest-bidder-wins-all is the most transparent system for awarding land, as it removes the need for the government to make subjective decisions, which can easily be politicised into a blaming game, said James Pong, chairman of the planning and development division of the Hong Kong Institute of Surveyors.

“Which design is better? This is a very subjective decision,” Pong said. “The government will be easily questioned by political parties that they have failed to ensure the best use of land resources and failed to safeguard the public interest.”

And that is not a system that could work under Hong Kong’s highly charged political system, said Richard Wong Yu-chim, Professor of Economics and the Philip Wong Kennedy Wong Professor in Political Economy at the University of Hong Kong.

And even if the current system were changed, home prices wouldn’t fall, because Hong Kong has ample supply of land, all held in the grips of developers, he said.

An estimated 1,000 hectares (2,471 acres) of land, mostly classified as farmland far away from urban centres, are held by Hong Kong’s developers including Sun Hung Kai and Cheung Kong Property Holdings, according to government data.

The administration of Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor is trying to make developers release that land hoard back for construction, through options like lower land-use conversion premium to encourage the land owners to build housing projects with the government.

Another option is to increase the plot ratio on land parcels as a way of compensating developers who sacrifice their profit margins for social housing, Wong said.

A better solution may be to follow mainland China’s housing market regulations, which set a price ceiling on the sale of land parcel owned by the state, which are essentially leased out to developers for building homes on.

“Property prices can fall if the government sets a ceiling for the completed homes before the land is put out for tender,” Pong said. “It works if the government is willing to sacrifice its land sale revenue by lowering the reserve price of the lot. Developers who are willing to accept the lowest profit margin win the project.”

That is easier said than done however, when many developers must also watch out for their shareholders’ interests.

That practice also inserts the government front and centre into the market’s operation, a practice contrary to Hong Kong’s laissez faire economy, which has put it as the planet’s freest economy for nine years in a row, according the Heritage Foundation’s data.

An alternative could be the use of price ceilings on land that is been zoned specifically for building state-subsidised housing to help lower-income homebuyers.

The government said they would review the land sale policy regularly, aimed to “maintaining adequate market transparency,” according to the Development Bureau.