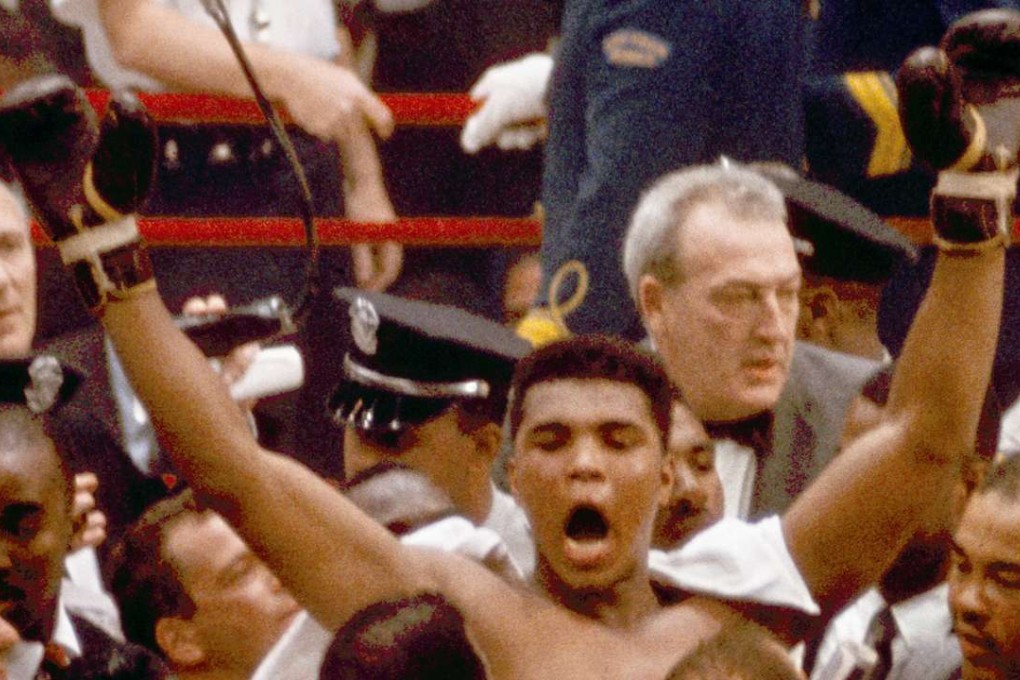

Opinion | Fear was only a word and not an institution for Muhammad Ali, which is why he truly was ‘The Greatest’

Live and let live and be afraid only of your conscience: Ali meant something to all of us

Tom Lysiak was a very good hockey player. Rick McLeish was as well. They just both picked a bad week because anyone who left the earth over the past seven days or so would have been overshadowed by the loss of Muhammad Ali. I mean, Muhammad Ali?

Introductions are meaningless for a man who once had the undisputed title of the most famous person on earth. Ali’s death is the most significant passing since Nelson Mandela left us a little less than three years ago and both men can be described in a single word: impact.

Theirs is a timeless and global appeal that clearly transcends South African politics and American boxing.

The faces may change, but the struggle for equality is as old as man itself and in that regard few personified the struggle in a more dignified and charismatic manner than Mandela and Ali.

Of course, dignity is in the eye of the beholder and those of us who actually have a fleeting memory of Ali the boxer may not necessarily think of his braggadocio and bombastic ways as being dignified.

Again, the man was not perfect and he would have been the first to tell you. But his greatest gift was a very personal one. We are all free to celebrate, or despise, different parts of Ali. You, me, your family, your neighbours, those you love and those you deplore, Ali may have meant something different to each of us. But make no mistake, he meant something to all of us.