Chinese soccer needs new way of thinking about youth development

Foreign coaches working on the mainland argue youth development is missing piece in puzzle

When Trevor Lamb first arrived in China, he was surprised how many jokes there were about football. And not one of them was complimentary.

"There were literally dozens of jokes about the game," says the American coach. "In fact, there still are. People associate football with poor quality and as a joke."

The most common gag is: "In a country of 1.3 billion people, we can't even find 11 players!"

As with all the best jokes, there is a painful ring of truth about it.

China are 93rd in the latest Fifa world rankings, in the slipstream of countries such as Oman and the Dominican Republic. The team failed to even make it to the final round of Asian qualifying for the 2014 World Cup and their nadir arrived in June, when they were beaten 5-1 at home by Thailand - a country ranked 47 places below them by Fifa.

So, joking aside, how can such a powerful nation be quite so bad?

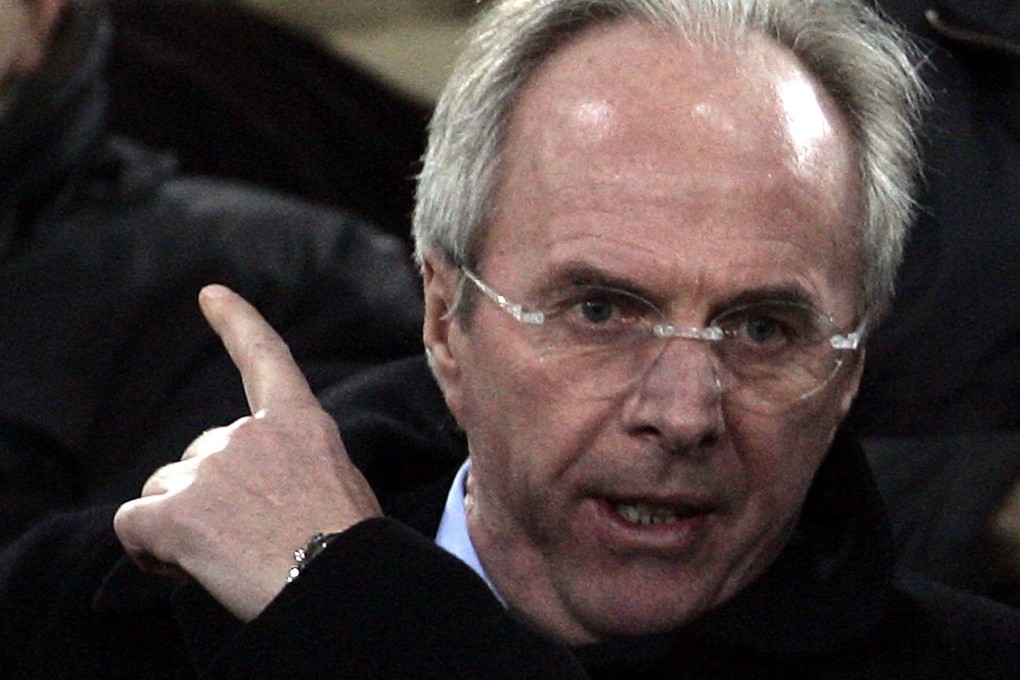

Former England manager Sven-Goran Eriksson, who took over Chinese Super League side Guangzhou R&F in June, says he was struck by how few kids play football on the streets or in parks in China. "If you go past a park in the city, they're not playing football like they are in parks in Manchester or London or wherever," the Swede said. "Football has never been a big, big sport in China and one of the problems is that there is no grass-roots football."