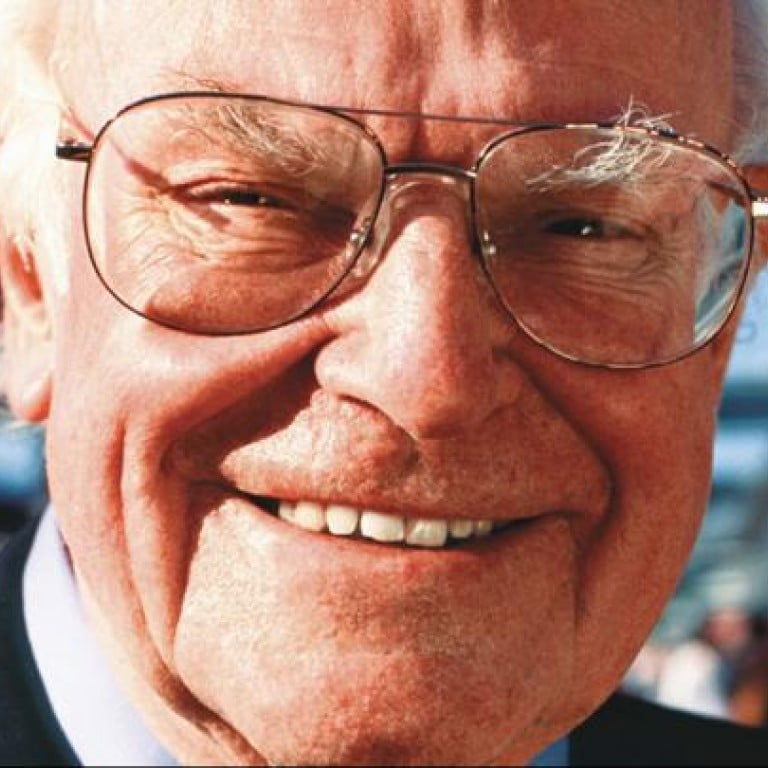

Farewell to the prof, the man who made F1 safe

Sid Watkins turned Formula One into a sport where deaths on the track are now unheard of

A lot has been written in this column over the years about safety in Formula One. That discussion has more often than not been framed through the efforts of Jackie Stewart and Max Mosley, the former head of the FIA, the sport’s governing body. Too often the contribution of Professor Sid Watkins has been overlooked.

The man who was the FIA’s medical delegate died last week at the age of 84. From 1978 until 2005 he was responsible for the medical team at races. But Watkins did a lot more than be on hand for accidents. When he started the job, driver deaths were commonplace. When he left the role seven years ago, they were unheard of.

Watkins was not just a doctor, but a campaigner. Over time he helped transform the medical centres at tracks and upgraded the medical cars. Helicopters became mandatory at F1 racetracks. It was not always easy at the start. Organisers at Hockenheim once refused him entry to the control room until Bernie Ecclestone, who had hired him, threatened to stop the race. The next year a new medical centre had replaced a converted bus at the German track.

The likes of Nelson Piquet, Gerhard Berger, Rubens Barrichello and Mikka Hakkinen are all alive today because of the work of Watkins. Hakkinen, for example, survived a crash in Adelaide in 1995 because Watkins performed a trackside tracheotomy.

But even Watkins could not save the life of his good friend Ayrton Senna. The 1994 San Marino Grand Prix saw the deaths of both Senna and Roland Ratzenberger, and Watkins witnessed both at first hand. After Ratzenburger’s death, a distraught Senna was comforted by Watkins. He spoke about it both in his autobiography and in the acclaimed film Senna.

He wrote that he urged Senna to quit there and then. “What else do you need to do?” he told the Brazilian. “You have been world champion three times, you are obviously the quickest driver. Give it up and let’s go fishing.” Senna replied that he couldn’t. It was the last conversation they were to have.

When, the next day, Watkins arrived at the scene of Senna’s accident and laid him on the ground next to the car, he said he sensed Senna’s spirit depart. Doctors experience such things regularly of course, but for it to be one of your good friends must have been crushing, especially in a sport Watkins knew could be so much safer.

After that tragic weekend, Watkins was appointed chairman of the FIA expert advisory safety panel and, working with others, he transformed the safety of the sport. The opposition to change that he had experienced melted away, and Formula One was transformed. The crash at Spa the other week in the conditions of 20 years ago does not bear thinking about.

Stewart had already stirred up a hornet’s nest over safety when he was a driver. He had been retired for five years by the time Watkins took up his Formula One position but saw a kindred spirit in terms of campaigning for safety. “He was responsible for more life-saving than anyone else, certainly since my day and he carried it off with the FIA to the point that the governing body then saw the necessity to have Sid permanently,” Stewart says.

Stewart feels there should be a permanent reminder to honour Watkins. It would be a nice touch for a man who has left such a mark on the sport. Whatever might transpire, the most fitting tribute is that no driver has died in Formula One since that grim weekend in 1994.

Perhaps the final word should be left to Bruno Senna, the Williams driver who is the nephew of Ayrton. He competes in a completely different sporting world to his uncle. He wrote on Twitter: “RIP Prof Sid Watkins. Sad news for us who stay behind”.