Lenovo’s chairman says worst is over for PC giant and ‘intelligent transformation’ set to reap rewards

- Lenovo has had to weather several volatile PC market cycles, and struggled to integrate its two 2014 acquisitions

- Lenovo aims to become a leader in data centre operations, leveraging its global PC platform

It has taken almost four years but China’s Lenovo Group has begun to see some rewards from the multibillion dollar acquisitions of IBM’s commodity server business and Google’s Motorola Mobility smartphone unit, with the company recently regaining the crown from HP as the world’s biggest personal computer (PC) maker.

The company in November posted a third, straight quarter of profit growth as its Motorola business broke even operationally and as its data centre unit posted much-reduced losses of US$3 million, allowing it to say it was on track to be a “sustainable, profitable growth engine”.

Chairman and chief executive Yang Yuanqing believes the worst is over for Lenovo, which has spent the past few years refocusing on mobile and smart devices, as well as its data centre services, in what the company has called an “intelligent transformation” to capitalise on the rapid growth of the internet of things (IoT) market globally, as well as the wider adoption of artificial intelligence (AI) and automation.

“Because of the past few years of laying the groundwork … we have all the assets needed to now push ahead in the field of automation [where processes can be conducted with minimal human inputs],” he said in a recent interview.

These assets, according to Yang, include the capacity to handle big data and powerful algorithms that can parse the information – generating applications for the medical, manufacturing and retail industries among others. These assets have been developed during the company’s long-haul transformation from a plain vanilla distributor of foreign PC brands in China, to a manufacturer, to expanding overseas via the acquisition of IBM’s PC business in 2005.

Along the way Lenovo has also had to weather several volatile PC market cycles, and has more recently struggled to integrate its two 2014 acquisitions – Google’s Motorola for US$2.9 billion and IBM’s low-end server unit for US$2.3 billion – at a time when the smartphone market became dominated by Apple and Samsung Electronics, and as the server industry was squeezed by a move towards cloud-based infrastructure.

Initial optimistic forecasts that both acquisitions would drive profitability quickly soured.

The traditional server business market took a dive immediately after Lenovo got into it as cloud computing took off. With the benefit of hindsight, Yang said Lenovo acquired an “infrastructure” business that was not “smart”, with cloud computing quickly replacing traditional IT architecture due to its power and efficiency.

With servers, networks and applications now defined by software, the devices and applications layer can be decoupled from the underlying infrastructure and hardware, allowing for servers, networks and storage space to be shared, said Yang.

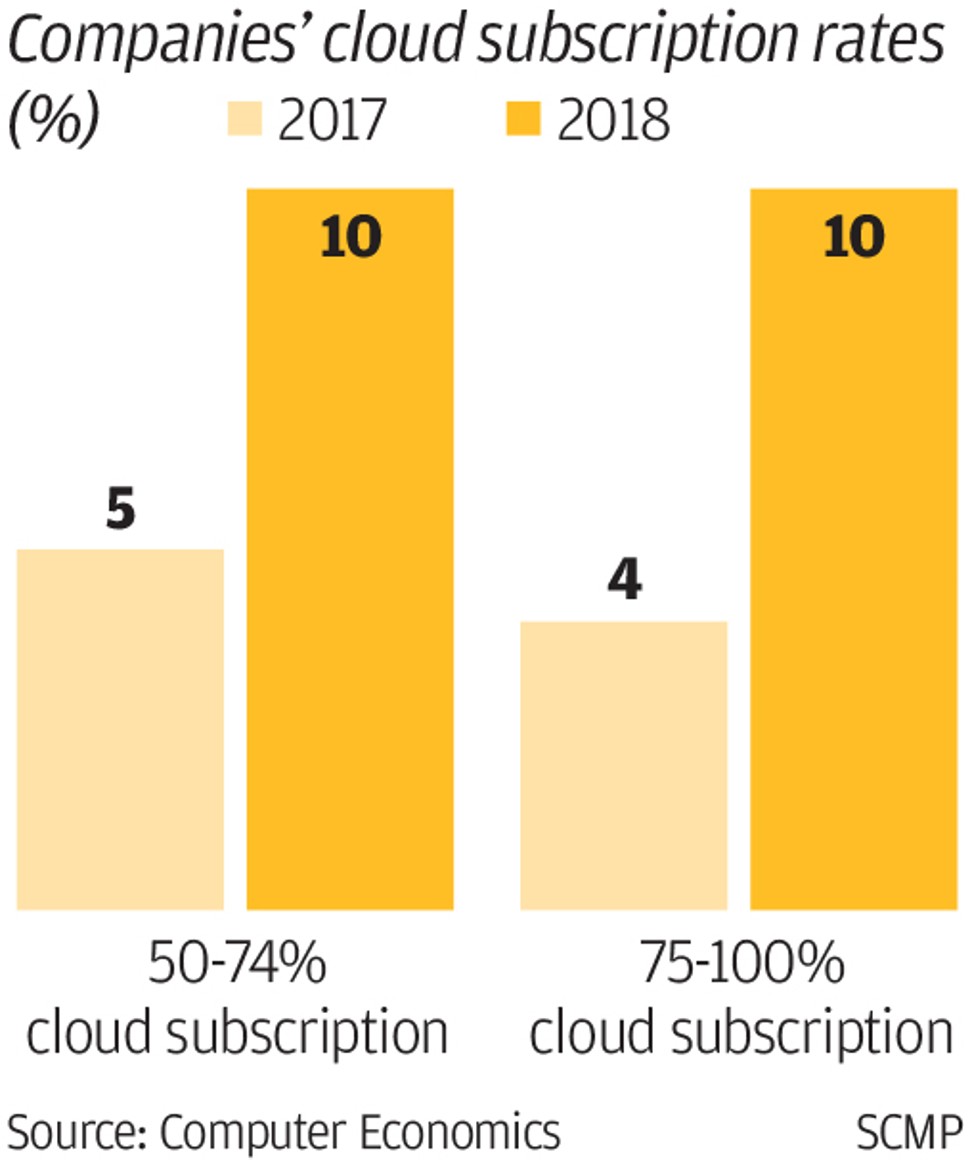

About 20 per cent of companies reported that at least half of their business applications are now cloud-based, rising from 9 per cent in 2017, according to the 2018/2019 IT Spending and Staffing Benchmarks report by US-based independent information technology research firm Computer Economics.

Yang said that getting rid of redundant assets and upgrading others has been Lenovo’s major challenge over the past few years. “We have been building new foundations over the past two years,” he said.

The company’s data centre group (DCG) registered its fourth straight quarter of strong revenue growth in the three months ended September 30, as pre-tax losses decreased over the previous quarter.

And its mobile business has finally escaped from a rut, according to Yang, thanks to cost-cutting efforts and exits from some markets.

In some ways, the Motorola purchase has presented the same challenges as the IBM PC acquisition of 2004, where Lenovo had to take the established IBM ThinkPad product and reinvent it while protecting existing brand value.

Chris Yim, an analyst at Bocom International Holdings, said the company has done well in hyperscale computing – an infrastructure market that research firm IDC has forecast to rise at a compound annual growth rate of just over 10 per cent to hit US$41.5 billion in 2022.

Hyperscaling is the ability of computing architecture to scale rapidly – meaning computing power, memory, networking capacity, and storage resources to the set of nodes that make up a larger computing environment – such as those adopted by technology giants like Google and Facebook.

Yim said that overall, the company’s “profit margins were kept at an ideal level”.

For the six months ended September 30, the bulk of the company’s revenue – US$22.12 billion or 87 per cent – came from the intelligent devices group (IDG) including PCs and mobile phones, with 12.5 per cent from the DCG segment. Although the DCG’s proportion of revenue has grown from the previous year’s 9 per cent, the segment remains in the red.

Lenovo said it returned to top spot in the PC market with a 23.7 per cent share, according to industry tracker IDC. Global PC shipments edged up 0.1 per cent in the third quarter of the year to 67.2 million units, according to data from Gartner, with Lenovo cornering the biggest share due to commercial PC growth and its joint venture with Fujitsu.

Investors have taken note of Lenovo’s progress and its Hong Kong-traded shares gained about 19 per cent in 2018, going against the grain of falling stock markets around the world.

However, with the end of the computer hardware replacement cycle looming in 2019, traditional PC and hardware makers like Lenovo that have shifted their focus to services and software will need to ensure that these new businesses offset the fall in hardware replacement orders.

In addition, the US-China trade war has made it harder for Lenovo’s DCG to sell its wares to large US companies, said Fubon Securities’ Arthur Liao.

“Although data centres have had four consecutive quarters of yearly PTI (pre-tax income) margin improvement, there is no room to the upside,” Liao said. “Overall, the worst appears to be over … but the tariff war between China and the US could impact its FY20 (financial year 2020) performance, as Lenovo is still viewed as a Chinese enterprise.”

Yang stressed that Lenovo is a global firm, with operations, research and development spread across 160 countries, although he acknowledged that competition remains as fierce as ever. But he said that Lenovo’s “intelligent transformation” has now put it on the front foot compared with some rivals.

“In this new era, [some of our] old rivals face new challenges. Previously successfully enterprises aren’t necessarily going to be successful in the future,” Yang said, without elaborating.

Lenovo aims to become a leader in data centre operations, leveraging the global platform and supply chain of its PC business, said Yang.

“The PC business has a major advantage; it is a business-to-business (B2B) and business-to-consumer (B2C) operation, which means we engage with both types of customers and [distribution] channels,” Yang said.

“Innovation is not exclusive to any one company or country. Every country has the right to upgrade itself and I believe this technological elevation benefits the entire human race. It is the same with globalisation.”