Ancient 'Superman' microbe's ability to withstand damage to its DNA could be key to unlocking cancer cure, Chinese scientists say

The earliest form of life on the planet may provide vital clues about how people can cope with environmental stress without increasing their chances of getting cancer, according to a new study by Chinese scientists.

Negative environmental factors such as excessive workloads, pollution or viral infections can trigger high levels of DNA damage by negatively impacting the way genomes replicate.

When a high frequency of mutations occurs within a cell, its genome becomes unstable, which can lead to various forms of cancer.

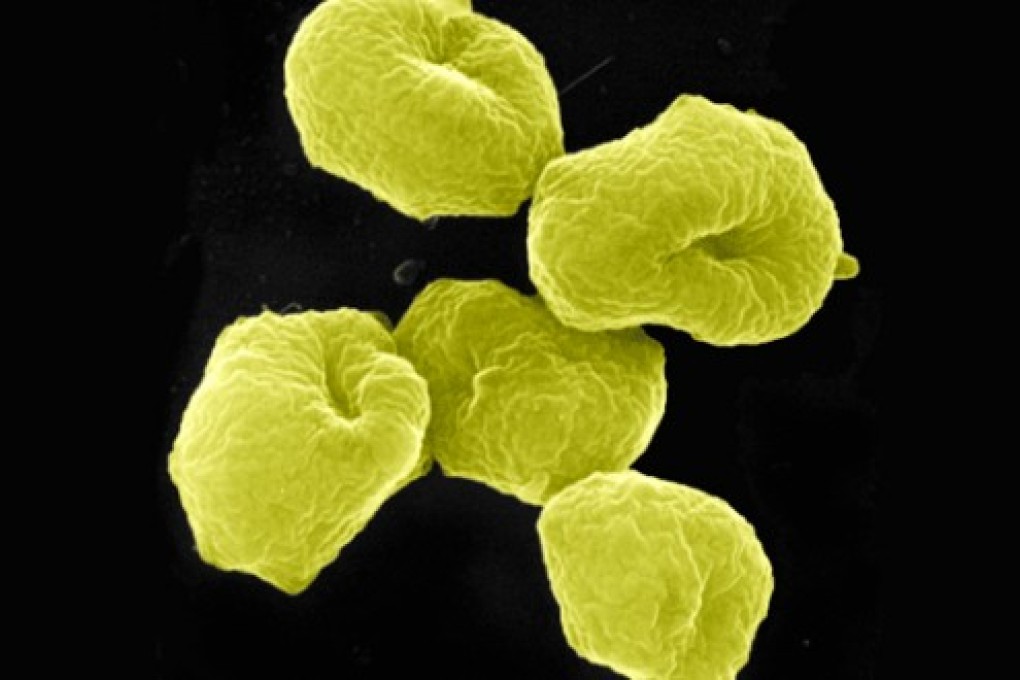

To explore issues of DNA replication, the Chinese researchers focussed on a common species of archaea, a single-celled microorganism that may have formed the first life on the planet around four billion years ago.

Called Haloferax mediterranei, it can be found in the sea from whence it draws half of its name. It feeds exclusively on nitrogen.

As archaea may be a common ancestor for all life on the planet, its mechanisms and processes can offer clues on how dormant genomes replicate under pressure – studies that are much harder to observe in humans.