New close-up photos of Saturn’s largest moon may be the last for decades

Scientists curious about a ‘magic island’ that consistently disappears and reappears in one of Titan’s shallow seas

NASA’s long-lived Saturn probe, Cassini, has paid its final visit to the planet’s largest moon, Titan.

The moon is larger than Earth’s and bigger than the planet Mercury. It’s covered in thick haze and smog, contains seas of liquid hydrocarbons, has a crust made of ice — and just might be habitable to alien life.

Cassini flew by the giant moon and photographed it on Saturday, less than two weeks after the probe captured an awe-inspiring image of Earth through the rings of Saturn.

The latest batch of images started arriving at Earth-based radio dishes on Sunday, after travelling 878 million miles through deep space. Scientists are now taking the raw black-and-white data and processing it into colour photographs.

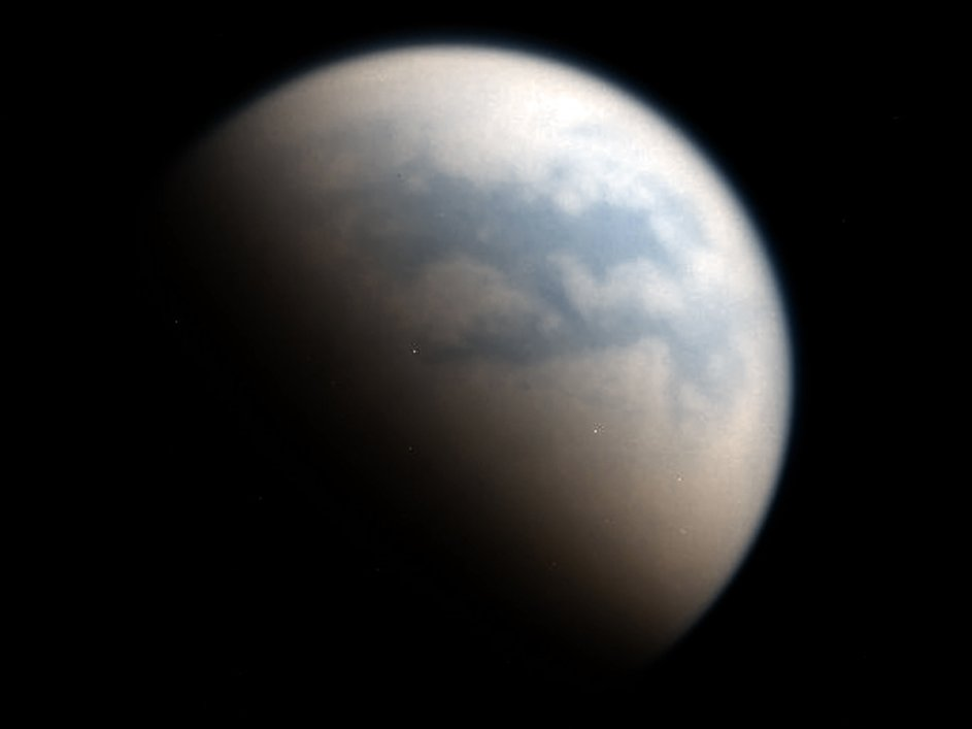

This shot, for example, merges red and near-infrared light — which can pierce Titan’s thick atmosphere — from Cassini’s camera sensor, revealing the partly-lit surface of Titan:

The blue-coloured regions are dark material that researchers believe are dry seabeds.

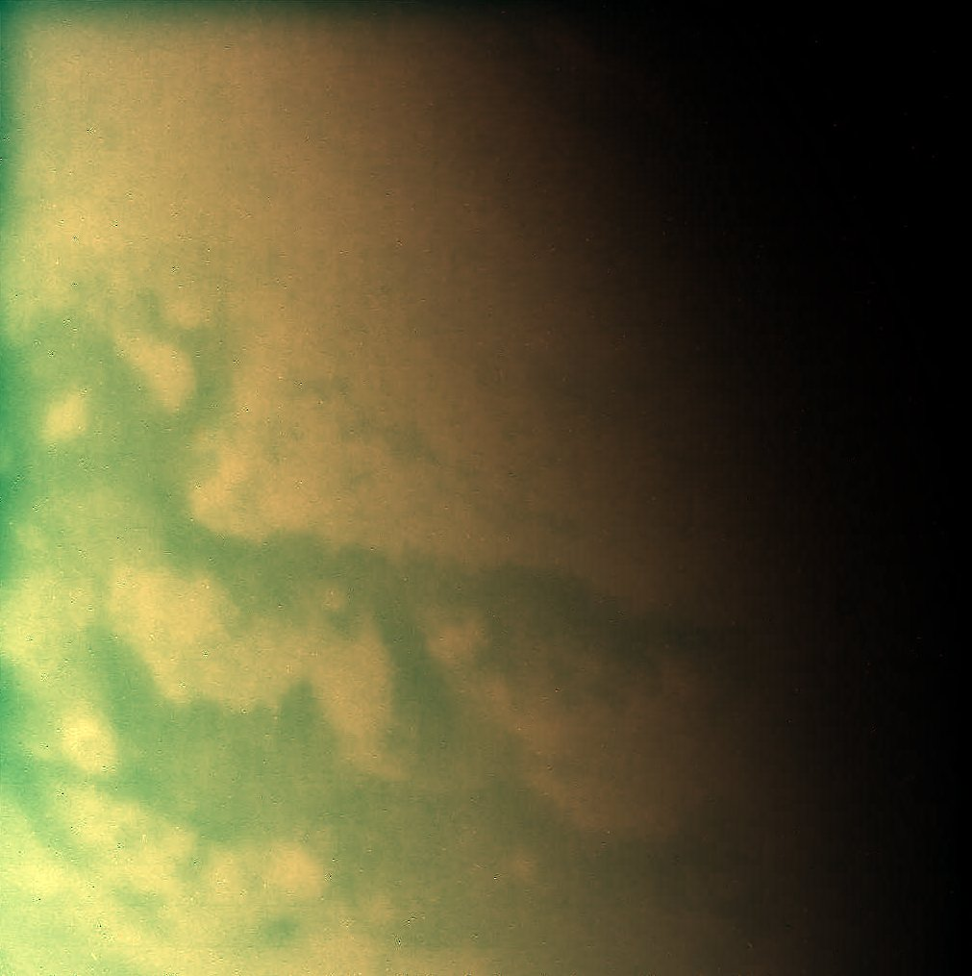

A closer view of Titan, likely taken within about 600 miles of the moon, more clearly shows some of those dark areas:

With these and dozens of other new images, NASA locked in its final look at the mysterious moon.

Scientists are especially curious about a “magic island” that seems to consistently disappear and reappear in one of Titan’s shallow seas over time.

“We don’t know what it is. It might be some hydrocarbon gas, and these bubbles periodically come to the surface,” Linda Spilker, a Cassini project scientist and a planetary scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, told Business Insider, adding that the gas might be methane or ethane. “This happens in lakes on Earth.”

NASA would prefer to continue exploring Titan and other bodies near Saturn with Cassini but has said its plucky probe is running out of fuel — and out of time.

NASA launched Cassini in October 1997, and the nuclear-powered probe reached the Saturn system after seven years of flight. After it dropped off a probe called Huygens in 2004, it began circling the planet and spying on its vast collections of moons and rings.

However, the mission will soon come to a fiery end.

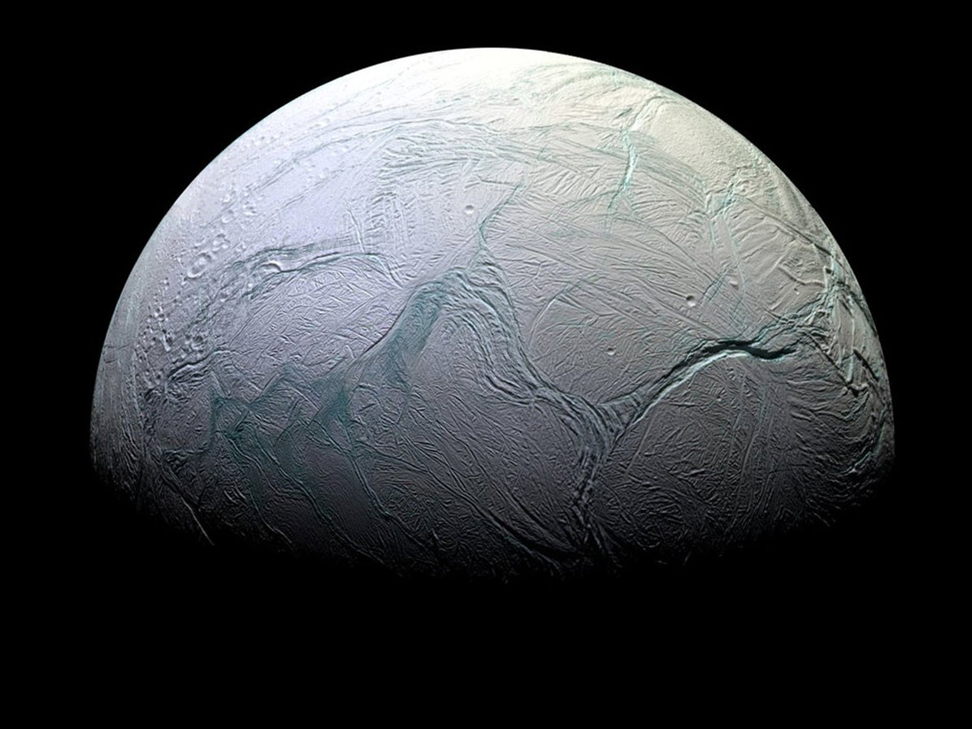

The spacecraft is dangerously low on a propellant that’s required to correct or change its orbit. Because Cassini has earthly microbes stuck to its body, scientists don’t want the probe to crash into and contaminate Titan or other moons like Enceladus, an ice-encrusted world that’s hiding a warm saltwater ocean.

So NASA is going to burn up the US$3.26 billion probe in the thick clouds of Saturn.

“Cassini’s own discoveries were its demise,” Earl Maize, an engineer at NASA’s JPL who manages the Cassini mission, said during an April 4 press briefing. “Cassini has got to be put safely away. And since we wanted to stay at Saturn, the only choice was to destroy it in some controlled fashion.”

Cassini’s Saturday fly-by of Titan marks the official start to what NASA calls the spacecraft’s “grand finale” — a new, risky set of orbits that will dive the probe through the relatively narrow gap between Saturn and its rings.

The first ring-gap dive is expected to happen on Wednesday, and Cassini will complete 20 similar dives in the coming months. But in early September, Cassini will swing close enough to Titan for the moon’s gravity to send the robot to its death.

“That final orbit gives us Titan’s goodbye kiss,” Spilker told Business Insider. (If we get any images of Titan from that last trip, they won’t be as close-up as this most recent batch.)

The probe will enter Saturn’s atmosphere on September 15, taking as many readings as it can before it breaks apart and burns up.

“I don’t think of this as killing Cassini. I see it as a glorious end to an incredible mission,” Spilker said. “It’s Cassini’s blaze of glory.”

It may be decades before NASA sends another probe to Saturn. There are currently no other missions to Saturn or its moons on the books, and although the US government is slowly making plutonium-238, a nuclear fuel that’s required to power NASA’s most ambitious robots, the space agency’s current stockpile has run too low to launch another Cassini.