How Trump and Turnbull dealt a double whammy to Indian techies

After all, the travel ban saga in January laid bare the dysfunction the White House was displaying in executing the most basic of its election pledges – Trump had bragged that the failed immigration curbs imposed on seven Muslim-majority nations would be in place on “day one” of his tenure. And besides, such sweeping changes on a complex visa regime could wreak havoc on the country’s financial and technology titans.

Can India’s IT sector thrive in world of Uber and Trump?

Sushma Swaraj, India’s foreign minister, was so confident the White House would make no change to the H-1B visa that in March she declared that Indian nationals working in the US had “nothing to worry about”. The H-1B visa – held by some one million people – is meant for skilled workers.

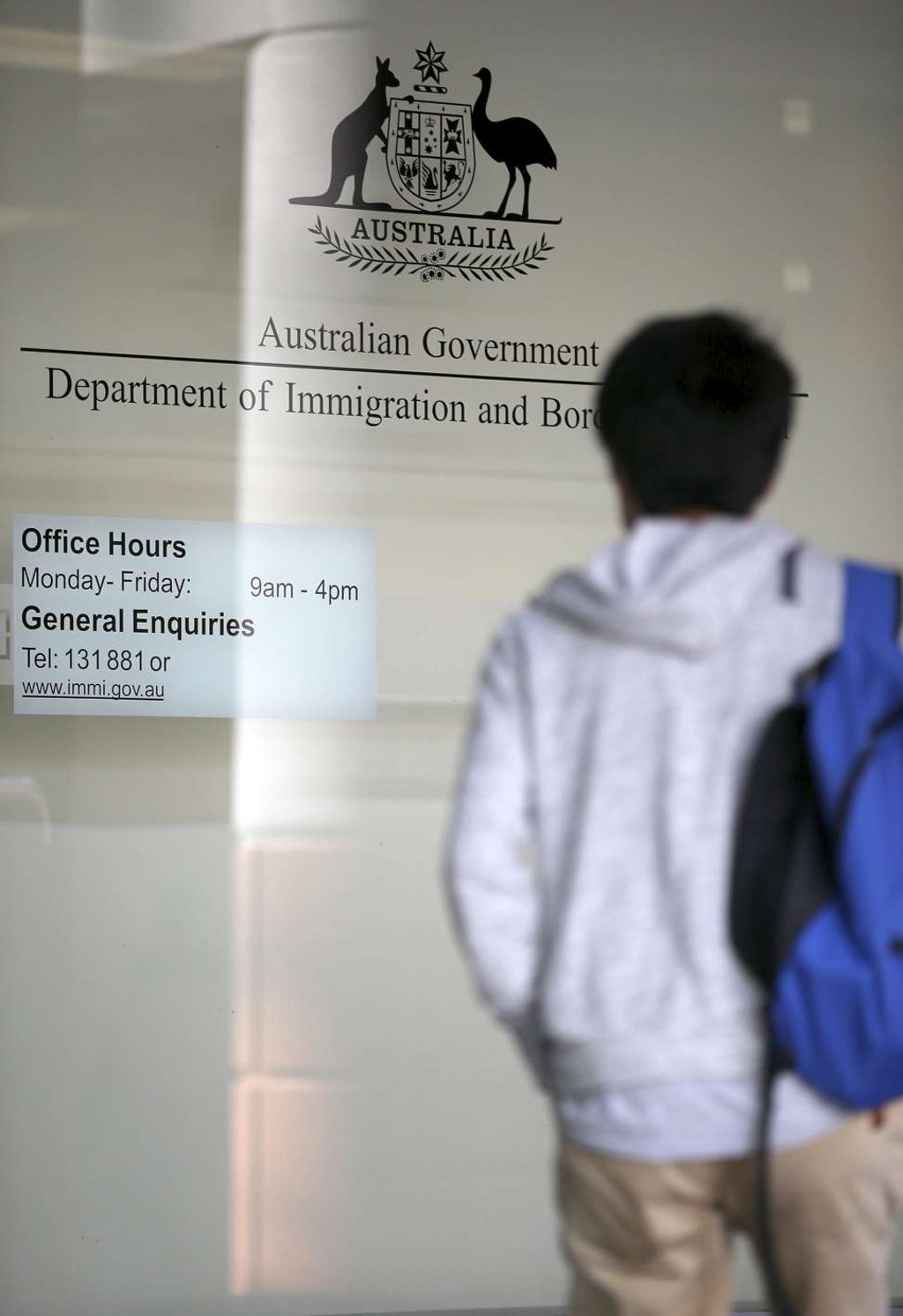

The minister’s jittery compatriots in Silicon Valley and elsewhere in the US proved to be more prescient, however, as Washington this week finally announced its plans to reform its visa regime for skilled workers. To add salt to New Delhi’s wounds, within 36 hours of the US announcement, its key allies Australia and New Zealand also unveiled plans for similar visa clampdowns.

Asian nationals – in particular the US$150 billion Indian technology sector – will be hit the hardest by the changes, observers say. In the US, the change involves moving the allocation of H-1B visas from a lottery to a merit-based system that prioritises the highest earners.