How India could Trump China as US policy shifts – in 12 charts

Drivers of Beijing’s economic miracle are past the point of diminishing returns and the country is awash in debt – the Indian economy’s rural-to-urban transition sets the stage for years of solid growth

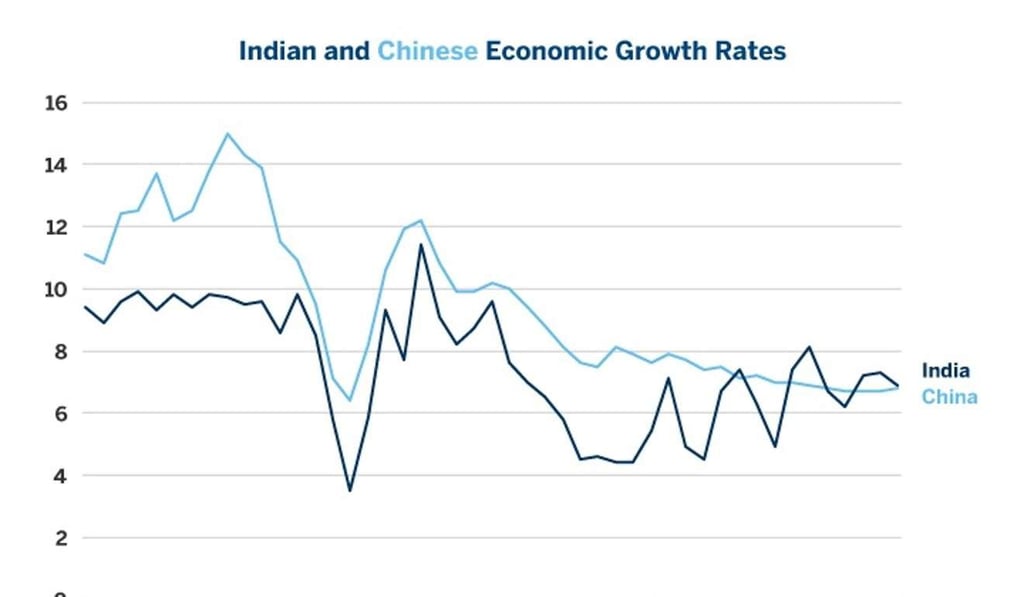

Neighbours and rivals, China and India have the distinction of being the world’s two most populous nations. With between 1.3-1.4 billion people each, they account for 36.5 per cent of humanity. But the similarities largely end there. Over the past three decades, China has become much more prosperous than India, with an economy five times larger. While India’s 4-8 per cent growth rate has been quite solid, it lags China’s red-hot pace, which topped 10 per cent for much of the past few decades.

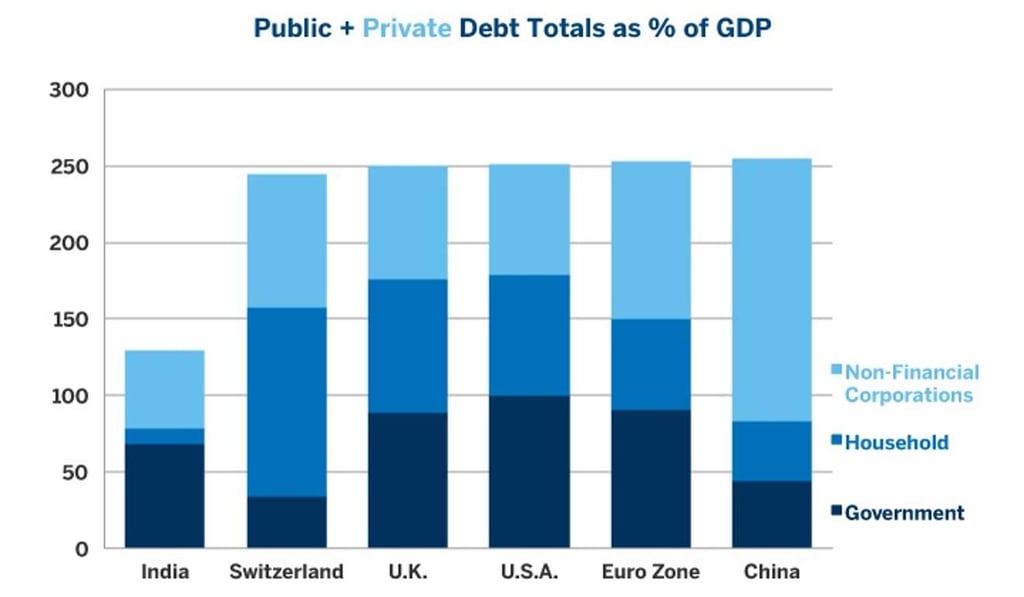

However, this dynamic has begun to change. Since 2015, India’s economy has begun to pull ahead of China’s. The drivers of China’s economic miracle, namely, a productivity-enhancing transition from being rural to urban based, and the impressive buildup of infrastructure are past the point of diminishing marginal returns. In addition, the country is awash in debt. China’s total debt (public + private) has grown to levels comparable to those in Europe and North America, and this portends slower growth.

Why China’s SUV sales can accelerate even as the economy downshifts

By contrast, India’s rural-urban transition, while well under way, is much less advanced than China’s and could boost India’s productivity for many years to come. India’s debt ratios are only half of those of China and have not been growing during the past decade. This, too, could set the stage for many years of solid growth in India that could begin to exceed that of China as we move into the 2020s. However, short-term growth in India could lag China’s as a result of the damage to the economy from Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s withdrawal of high-denomination currency notes in an effort to crack down on the country’s vast shadow economy.

Debt levels correlate strongly with both economic growth and the level of interest rates. Yet in both cases, the relationship tends to be a chicken-or-egg sort of problem. Less volatile economies, which are often the slower growing ones, can support high leverage ratios. But high leverage ratios can slow economic growth. Low interest rates can encourage credit growth and high debt ratios. High debt ratios, in turn, necessitate low interest rates so that public and private debt burdens can be financed.

When debt ratios are low, a country can grow by increasing leverage. One person’s spending or investment becomes income for somebody else. As debt levels rise, however, further borrowing serves mainly to service existing loans, and economic growth tends to slow. Eventually, interest rates will be forced down to very low levels as has happened in Japan, Europe and North America. China is already well down this path. India is not.