Chinese investment in Canadian oil shows bigger isn’t always better

An under-the-radar approach that avoids public criticism has helped smaller, private mainland investors succeed where the state behemoths have largely failed

The Communist Party’s third plenum pledged in late 2013 a “decisive role” for market forces. Critics have been debating ever since to what extent the central government is committed to that pledge. But there is one investment area, admittedly somewhat obscure, in which it has pursued that goal: private Chinese investment in oil and natural gas in Canada.

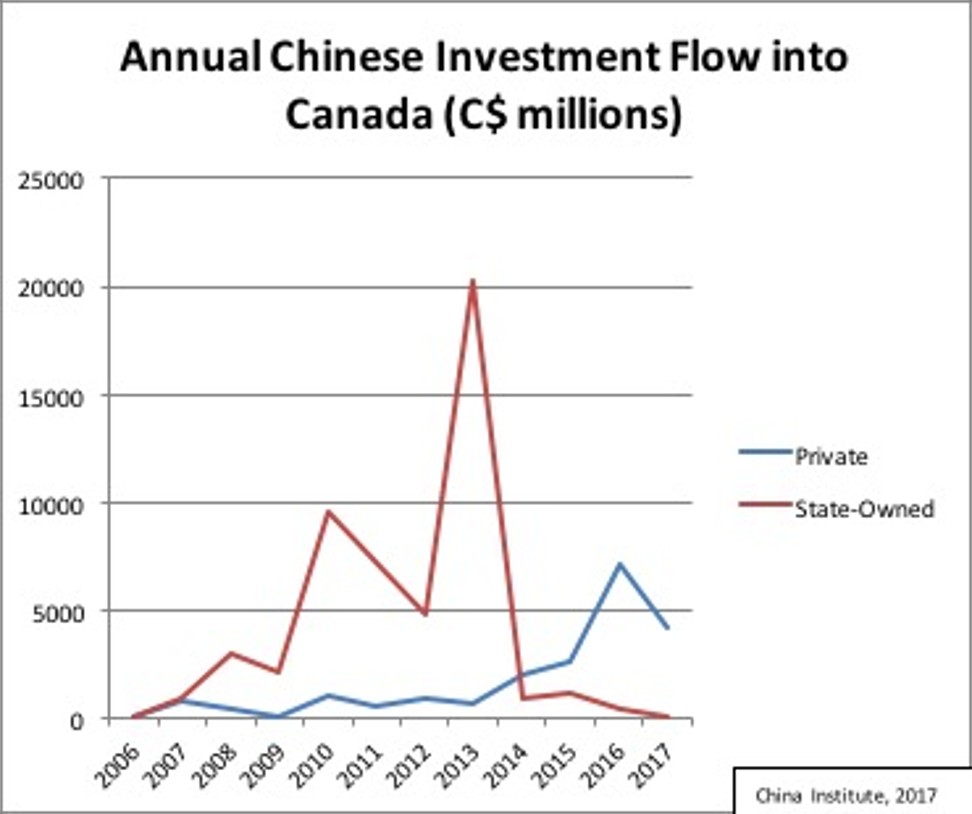

Early this decade, the big three state-owned oil giants, Sinopec, CNOOC and PetroChina, made headlines with megadeals, especially those involving Canada’s abundant but expensive-to-extract oil sands.

134 billion reasons for Mahathir not to rethink Chinese investment

But the outcome has been anything but smooth, as the transactions were often mired in political controversy, and operational and integration issues. In recent years, investment has slowed and ambitions moderated. In have come the small and medium-sized mainland investors that few people have heard of outside the industry. They take advantage of low oil prices and the industry slump by snapping up Canadian energy companies, many from the oil-rich Alberta province, and quite a few in financial distress that can be had for a song. Most investments focus on the more traditional oil and gas resources, rather than oil sands.

Between 2013 and last year, smaller private mainland investors have taken over at least a dozen Canadian energy companies, according to Alberta government records. Now, people are taking notice, as oil is again touching US$80 a barrel, proving such private entities may be nimbler and more driven by quick profits than the state behemoths.

ZTE mess shows need to change the ‘Chinese way of doing business’

A handful of commercial groups with close ties to mainland financial sources have pumped about C$4 billion (US$3.11 billion) into Alberta’s oil and gas sector since the onset of the oil price slump.

Among these are Shanghai Energy, which bought the oil and gas assets of bankrupt Endurance Energy in 2016 for about C$130 million; and Sequoia Resources Corp, which took over loss-making natural gas wells from Perpetual Energy, along with a C$133.6 million clean-up bill.

Spyglass Resources, a junior Canadian oil producer, was taken over for about C$60 million, less than half of the debt owed to creditors when it was pushed into receivership in 2015.

Quite a few deals backed by mainland capital range between C$30 million and C$60 million, small compared to the usual overseas deals completed by China’s big oil.

By comparison, two investments made by units under Shanghai-listed Changchun Sinoenergy are large: the takeover of New Star Energy in 2015 for C$215 million and the purchase of bankrupt Twin Butte Energy for more than C$260 million in late 2017.

China-linked oilmen who make small and mid-sized investments under the regulatory radar have got around many challenges faced by Chinese Big Oil in Canada

Such deals work well for Chinese investors without alarming Canadian regulators. Paradoxically, it was those mega energy deals, especially in oil sands, early in this decade that caused a backlash against Chinese state investment in Canadian energy resources and paved the way for the current mostly private and moderate-sized transactions.

In 2013, CNOOC completed its purchase of oil and gas giant Nexen, which was China’s then biggest outbound investment at C$17.4 billion. But it sparked much angst among the public about the suspected Chinese takeover of a pillar of the Canadian economy. Then conservative prime minister Stephen Harper allowed the sale to proceed but declared any such deals to be off limits in future and that others of significant size must go through federal regulatory scrutiny.

US trade war: when the (micro) chips are down, Chinese cash flows to Israel

For China’s big three oil giants, all that was a costly lesson. Canada may have rich oil and gas resources, and is politically stable compared with the Middle East, but it presents other political and cultural challenges.

Many Canadian activists are not only suspicious or critical of China’s authoritarian government, but are also environmentalists fiercely opposed to oil sands extraction, even by fellow Canadians. As the name implies, extracting the unconventional viscous oil called bitumen from sands and consolidated sandstone is technically difficult, economically costly and environmentally damaging. So, even though Alberta, the province with the most oil and gas deposits, may be welcoming to foreign, including Chinese, investment, it often stands alone against the rest of the country.

Hostility to Chinese investment is work of a minority, says Indonesia’s finance minister

China-linked oilmen who make small and mid-sized investments under the regulatory radar in conventional oil and gas have got around many of the challenges faced by Chinese Big Oil in Canada.

Of course, things are rarely so clear-cut. Canadian critics of shadow Chinese state investments have argued that the ownership of those mainland-tied companies are murky and could well involve stakes held by state-owned enterprises.

One oft-cited example is China Energy Reserve and Chemicals Group (CERCG), a Beijing-based specialist in the storage of oil and natural gas. The group made headlines in Hong Kong this year for having to withdraw its 55 per cent stake in a consortium to buy Li Ka-shing’s flagship The Center in Central, which eventually sold for a world record HK$40.2 billion (US$5.12 billion).

Calgary-based Shanghai Energy is ostensibly a private Canadian company, but according to a Globe and Mail investigative report, it is a subsidiary of a subsidiary owned by CERCG. CERCG, in turn, is co-owned by a subsidiary of the China Economic Cooperation Centre, a state organ. Of course, none of these necessarily proves a nefarious design.

Why no one gains from Australia and Britain’s treatment of Chinese investment

The obvious counter-argument is that those deals are so relatively small compared to the total size of the Canadian oil and gas sector that they can’t possibly pose a threat to the country’s national energy security. As well, they often involve risky assets that might otherwise be hard to find buyers for. If Canadian critics object to them, they might as well object to all foreign investment.

In light of persistent controversies dogging China’s state investments in so many economic sectors around the world, privately driven deals in Canada’s energy industry may prove a viable model to get around those divisive issues while allowing Beijing to free market forces for foreign investments. ■