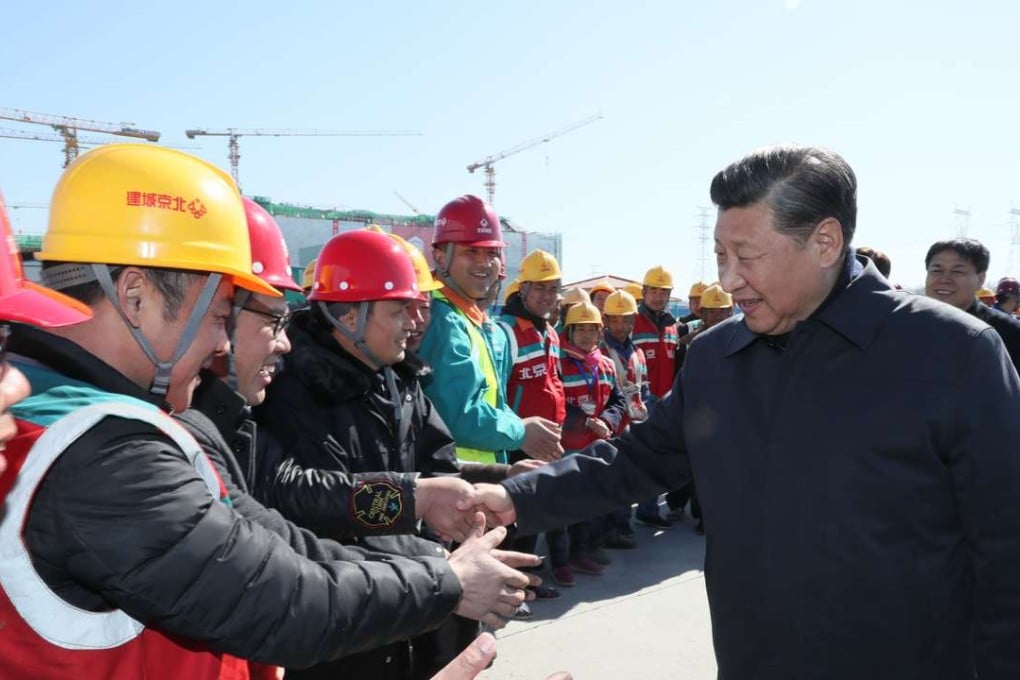

Xi all powerful? What Trump needs to know about Chinese politics

China may have a one-party system, but claims of President Xi Jinping’s rise to absolute power ignore the influence of the tuanpai

Analysts in both the United States and China surely understand that concerns at home drive policies abroad, but when surveying China’s domestic political landscape, the forest has sometimes been missed for the trees.

In Beijing’s system, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) holds a monopoly on power. But the party leadership is not a monolithic group. CCP leaders span a range of political associations, socioeconomic backgrounds, professional credentials, geographic associations and policy preferences. Two broad camps in the leadership vigorously vie for influence and control in post-Deng China: the “elitist coalition”, with its core faction of princelings (leaders who come from veteran revolutionary families), and the “populist coalition”, which primarily consists of so-called tuanpai (leaders who advanced their careers through the Chinese Communist Youth League).

Why China, India and the Dalai Lama are pushing the boundaries in Tawang

While not all analysts accept the validity of this “one party, two coalitions” framework, it is nevertheless useful to conceive of political power in China as a pendulum swinging between competing camps. The overriding goals of preserving CCP rule with broad support from both elites and the public keep factionalism in check, giving way to a rhythm of competition and power-sharing. On the eve of the 19th Party Congress, momentum unambiguously favours the elitist coalition, led by Xi, so it is no surprise that countless reports have emerged asserting his vice-like grip on power. But Xi’s impressive moves to promote protégés merely reflect the latest oscillation in the clockwork of Chinese elite politics.