Doklam then and now: from British to Chinese interests, follow the money

A stalemate in the Himalayas, a three-way territorial struggle, fears of foreign hegemony and dreams of a commercial invasion involving the centre of world manufacturing ... sound familiar?

On February 16, 1768, the Court of Directors of the East India Company in London wrote to Warren Hastings: “we desire you to obtain the best intelligence you can whether cloth and other European commodities may not find their way to Tibet, Lhasa and the Western parts of China.” This spurred the British exploration of the Himalayas, an effort that has led today to the face-off between the two giant armies of India and China, who now stand on the brink of war.

During the 18th century, chambers of commerce in towns across Britain met and demanded the British government build roads to open up Tibet. They envisioned a future in which the people of Tibet would be “wearing clothes manufactured in Manchester and eating with cutlery produced in Sheffield, and the caravans bearing silk and tea of China [would] come saving half the time and expense through the passes of Sikkim and Bhutan”. The British dreamt merchants from Paisley, Dundee, Bradford and Aberdeen “shall dip their pitchers into the sacred stream, and deal out its bounty to the people of the land”. Captain G. Chenevis, the British trade agent in Leh, wrote that “in the direction of Tibet, a commercial invasion of that mystic country with riches of Szo Chan and Kansu and Shensi in China as the objective, would I believe, be profitable”. The Bradford Chamber of Commerce declared such an outcome would boost the wool trade, while the British-run Calcutta Chamber of Commerce spelt out the international implications of this thirst for wealth: “there should be no power vacuums, no border Alsatias, which could be filled by others.”

WATCH: Indian border troops crossing into Chinese territory ‘very serious’: Chinese FM

Towards the end of the 18th century, it was the Indian Tea Association, with offices in Calcutta and London, that carried out much of the lobbying of the government to establish new markets in Tibet, Central Asia and Russia. The Indian tea magnates lamented the failure to break open the Tibetan market. The first chairman of the Indian Tea Association was Sir Douglas Forsyth, who had been in Leh and taken on the task of opening trade with Central Asia. Now, as the Tea Association’s new president, he had his eye on new markets. The Tibetan fondness for tea had been noted by numerous travellers, and until then all the tea consumed in Tibet had been imported from China using yaks and mules at a considerable cost. The Bengal Government asserted that tea could be exported from Darjeeling at “a fourth of the price” of Chinese tea. It was the high point of British imperial mercantilism, when the cities of Britain were primary producers and the rest of the world was seen as its consumers.

Dispatch from Doklam: Indians dig in for the long haul in standoff with India

The British advances into the foothills of the Himalayas did not go unnoticed in Lhasa and Beijing. The Tibetans, who described the British penetration as “oil seeping into a cloth”, resisted British attempts to establish trade routes into Tibet and watched with trepidation as the British forged a network of railways and roads on the southern edges of the Himalayas to speed up trade. The Tibetans hoped the geography of the Himalayas would provide protection against these advances, but also took other steps – in 1886, the oracles were consulted and new images of deities were installed in the Potala Palace to ward off the advancing British. This did not help the Himalayan Buddhist kingdoms to the south, which had already been annexed to British rule. Lahaul and Spiti was prised from Ladakh and became British territory, while Bhutan and Sikkim lost vast tracts of their territories to the British through inducement and coercion.

British emissaries to Tibet throughout this period were turned back, and official letters were returned unopened. The Tibetans’ refusal to engage with the British was fuelled by the fear of the Chinese response, since any attempt to engage with the British would prompt further Chinese intervention. Tibet’s isolationism suited the Chinese, who saw Tibet as a back door to their territories, much as India today views any opening of Bhutan to China as a threat to India’s security.

Road to Doklam: When will China and India start talking about the 1962 war honestly?

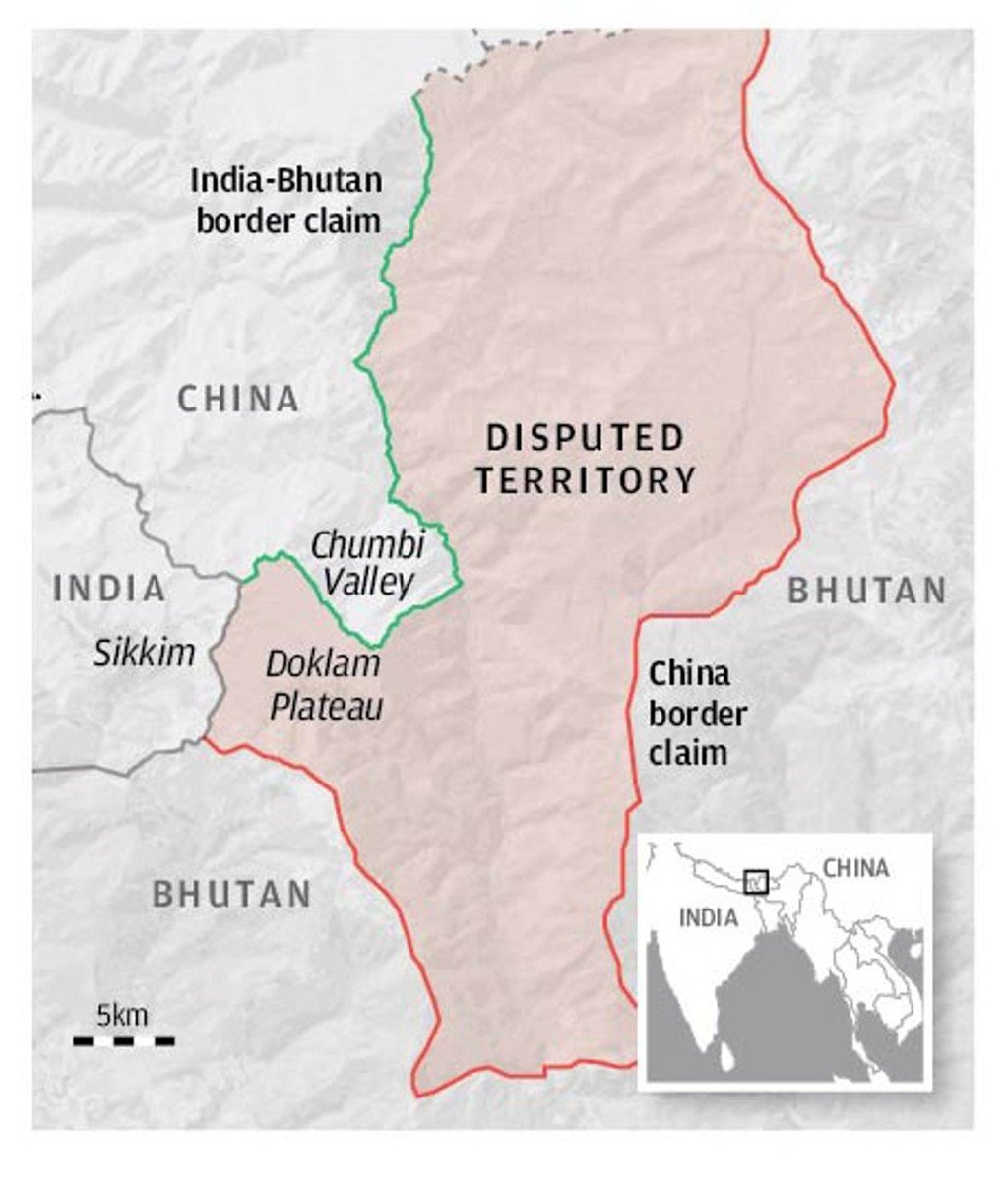

The initial British plan to open up Tibet involved constructing a road through Bhutan that would most likely have gone through the same location as the road now being built by the Chinese at Doklam, the site of the current stand-off. This would have been the shortest route leading to the main trading centre within Tibet at Phari. Bhutan saw the extension of roads as a slippery slope that could lead to annexation by the British and was not willing to concede. Despite repeated British inducements and threats, Bhutan refused to join the club of Princely States and managed to remain independent.