Is China to blame for the North Korea crisis? The answer depends on who you ask

The feud over how North Korea should be handled is an indication of the struggles between Washington and Beijing to communicate on an even level

In the final week of 2017, US President Donald Trump made crystal clear what his approach to China would be in the new year.

Chinese politics, North Korea: the economic dark clouds to watch for in 2018

China gave a stout response to Trump’s accusatory tweets – although it was largely ignored by the international media. The Foreign Ministry’s account stated that the ship in question operated outside of China’s jurisdiction after August 2017 and uploaded oil in another country before heading to waters close to North Korea. The UN resolution that banned unauthorised oil shipments was passed on December 22 – hence, China should not be held responsible.

The Chinese reply was met by silence – a possible sign that the tweet-happy US president was conceding the point.

As a reliable ally of the US, the South Korean government should have mounted a tremendous effort to help clear the air. But, at least in the mainstream English-language media, Seoul has chosen to remain silent over the Beijing-Washington feud.

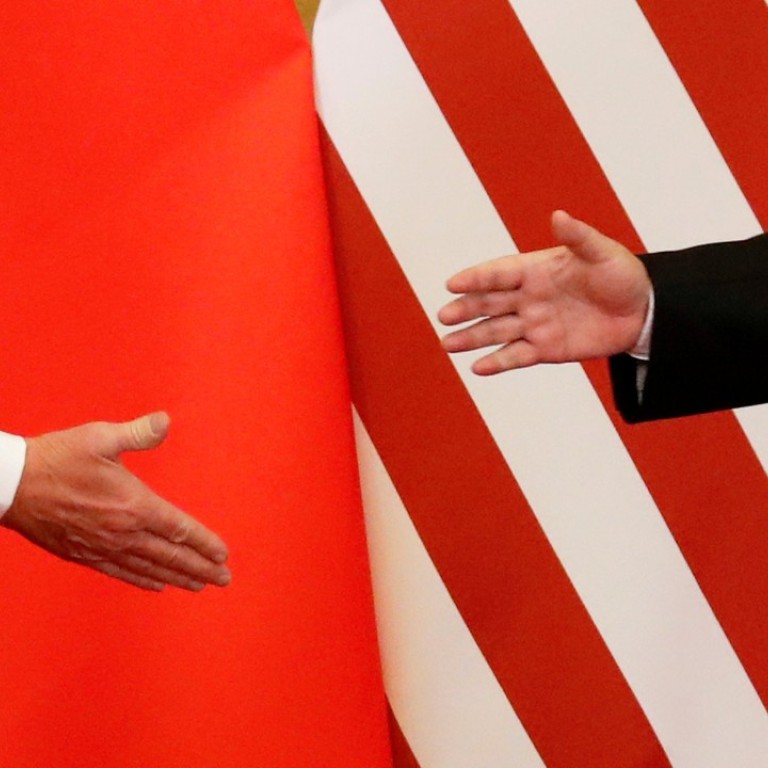

The dispute over the alleged oil sales – and how North Korea should be handled in general – is an indication of the struggles between Washington and Beijing to communicate on an even level.

China should cut oil exports to North Korea by half: Ban Ki-moon

The recent escalation of the dispute over North Korea can be traced back to the Mar-a-Lago meeting.

Did the Chinese team explicitly reject the conditions related to North Korea that Trump is now publically placing on how he handles trade and other issues with China?

Public information about the trip leaves little in the way of answers.

Here lies the first layer of asymmetry between Beijing and Washington: what is viewed as an agreement by one side can turn out to be a source of profound disagreement by the other – despite each side claiming to approach the other in good faith.

A second asymmetrical layer to relations stems from the narrative of what one nation has meant for the other’s fortunes post-second world war. Many Americans insist that China’s wealth is based on two essentials: access to American import market and raw materials from abroad.

The US thirst for made-in-China products is, by its own nature, a transfer of wealth. The US, and its allies, pays with cash and blood to keep trade routes open for ships carrying goods in and out of Chinese ports. As some believe, the pillars of China’s recent success are made in America. Flowing from this line of thinking, China owes the US a level of gratitude but has fallen short in failing to honour its commitment on North Korea.

But to many Chinese – and this has little to do with ideology, Communist or not – China’s economic rise was in spite of the US, not because of it.

Their reasons would include the US, and its allies, using diplomatic and military ends to keep Taiwan separated from the mainland. Even in bilateral trade, the US, along with the European Union, has made attempts to block its market economy status, which was promised when Beijing joined the World Trade Organisation and would treat it on par with other members when it comes to accounting for the costs of exported products.

As such, it is China that is bending over backwards to accommodate the US and it’s the US that keeps moving the posts of cooperation.

In a nuclear crisis over North Korea, why ignore the South?

There is nothing “wrong” with either side having such vastly divergent views about themselves and each other – after all, we see the world through our own prism. Nation building is above all a continuous process, and that is true for the world’s largest economies as well.

In the year ahead – and in years to come – the real challenge for both Beijing and Washington is whether they can use introspection to find ways to broaden, rather than weaken, the bilateral ties and shape diplomacy in responsible ways. The recent incident in the Yellow Sea is just another reminder about how close miscalculation is lurking, regardless of vast reservoirs of good faith and goodwill. ■

Zha Daojiong is a professor at the School of International Studies, Peking University