For Korea’s divided families, the time for reunions is running out

After 68 years of separation, the number of Korean families with members on both sides of the border is dwindling fast. And as they die out, so too does the power of Kim Jong-un’s mantra ‘one blood, one people’

When war between the two Koreas broke out in 1950, Jeon Ki-young gathered everything he could carry and fled south from his home in Pyongyang. As the eldest son of a wealthy landowner, Jeon was tasked with helping his entire family, including his siblings and grandparents, make the journey safely.

Through the chaos and bloodshed, Jeon and his family reached the Hangang river, which runs through the middle of Seoul, the modern South Korean capital, only to find its 1,005-metre-long bridge had been bombed to prevent an invasion by North Korean troops. Luckily, unlike most refugees, Jeon and his family were able to swim and so narrowly escaped the iron curtain. Unfortunately, one member of Jeon’s family did not make the journey. “His mother was still in Pyongyang,” explains Kim Seo-yeon, Jeon’s granddaughter, 28.

Jeon assumed he would return north and be reunited with his mother in a matter of days. But even after the two Koreas reached an armistice agreement in 1953, they remained separated by the 38th parallel. “She continued to live in the North after the war,” Kim says.

In the 1980s and 1990s, when inter-Korean family reunions became possible, Jeon grew hopeful. “He applied to meet her again, but the opportunity was not given to every person,” Kim says.

Hang on, what language is Kim Jong-un speaking?

Jeon never did get to see his mother again. He has since died, leaving his granddaughter and her family as the only ones to tell his story and, in doing so, invoke the memory of a once-unified Korea.

That announcement has given new hope to the 57,920 remaining registered family members in the South who, like Jeon once did, dream of seeing their loved ones once again. Their hopes have always been slim – there have been just 21 family reunions since the first one in 1985 and on each occasion, fewer than 200 families were selected via lottery to take part. And even with Kim and Moon clearing the way for more such meetings, those hopes are only getting slimmer.

Most members of these divided families are now in their late 80s and 90s, and running out of time. Each month, between 300 and 400 people on the list die.

Abe’s nuclear disaster: why has Japan been shut out of North Korea talks?

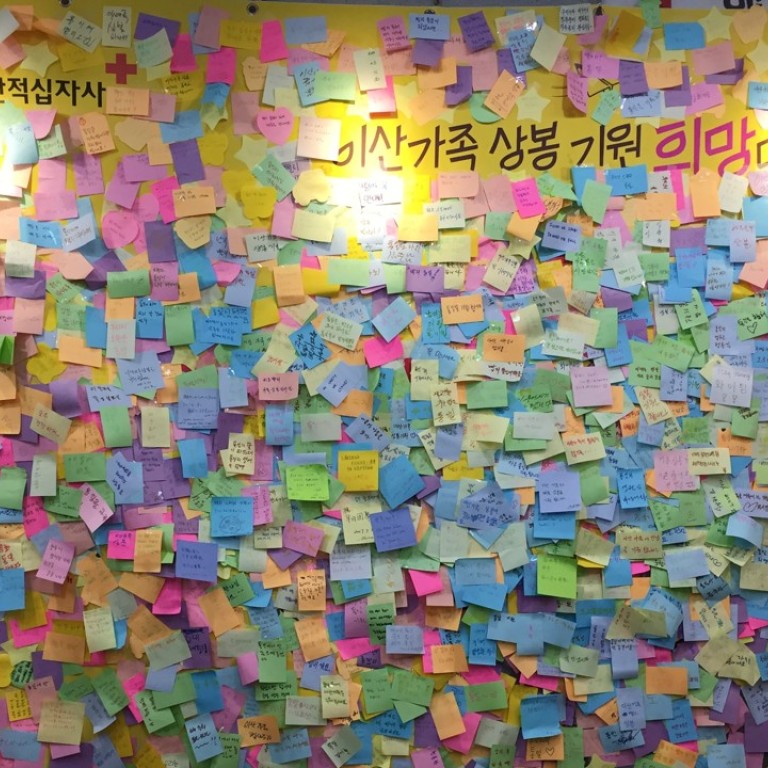

“We are definitely aware that these families are getting older and of the challenges we face conducting these reunions,” says Jung Ja-eun, the head of the inter-Korean cooperation team at the Korean Red Cross, the official South Korean organiser for the family reunions. “Since 2016, the number of deceased family members has become greater than those who are still living.”

As the number of divided families diminishes, so too does the power of unification mantras like “one blood, one people”, as championed by Kim in his speech during last week’s summit. Whether a younger generation has the inclination to uphold the legacy of a unified Korea remains to be seen.

“At my age, my friends don’t care about meeting with North Korea,” says Na Jong-bae, 36, a South Korean office worker. “Personally I don’t know anything about the family reunions, although I’m interested in ending this war.”

Young people in South Korea have become jaded when it comes to North Korea, says Michael Lee, 26, a writer whose maternal and paternal grandparents also came from the North during the war.

Are US and China sincere partners in disarming North Korea?

“We’ve grown up in the time of the Sunshine Policy, and then the deterioration of relations between North and South Korea,” he says, referring to the softening of South Korean foreign policy towards Pyongyang late last century. “We’re a very different generation. To young Koreans, there are [also] much greater issues in South Korean society than dealing with this very abstract pariah state. We’ve been hearing about North Korea since we were young and it gets a bit old.”

For others, the pressures of adult life have taken priority over the distant goal of reunification.

“I cared more about reunification and North Korea when I was a teenager,” says Nam Tae-woo, 27, a rock-climbing instructor. “But after graduating from university and doing my military service, all my attention went into trying to make money, getting a job, trying to survive and find a career.”

Too much time has passed since the separation between North and South, he adds: “North Korea is an entirely different country now. It’s not just about the linguistic differences – the cultural differences [and lack of mutual understanding] are even greater.”

Kim Seo-yeon says it’s understandable that young South Koreans who (unlike her) do not have any family in the North would feel this lack of connection, but says “this is why we need to increase our connections [and exchanges] with the North.”

Until the family reunions issue returned to the spotlight, North Koreans were rarely humanised in South Korean media, instead cast as untrustworthy spies, bloodthirsty soldiers, and as a brainwashed population in general. The reunions serve as a reminder that North Koreans may in fact be family.

“We only see Kim Jong-un in the news, or with the missiles and the nuclear mushroom [cloud] … one of the few ways for us to humanise North Koreans is to see them, to meet real North Koreans who currently live in North Korea,” says Joo Se-jin, 26, a researcher at the Export-Import Bank of Korea.

One way for South Korea to foster more exchanges is by reviving Kaesong Industrial Park, says Joo, referring to the collaborative special economic zone located in North Korea, where 123 South Korean companies employed 53,000 North Korean workers until 2016. “I don’t believe in Kaesong Industrial Complex’s economic effect but it has more of a political impact on South Korea,” she says. “At least we can meet North Koreans who work there. We should make contact with the North Korean people, not just between country leaders at summits.”

Others believe more official dialogue between the Koreas would help and that Kim himself needs to be portrayed in a more relatable light.

“I think the South-North summit that took place last week was a great example that showed the humane side of North Korea,” says Kim Jae-yun, a 25-year-old graduate studentat Ehwa Women’s University in Seoul. “South Koreans were witnessing Kim Jong-un laughing and making jokes for the first time … We were shocked because we often saw North Koreans only as soldiers or the poor, and not [as real people].”

As for the family reunions, their days may be numbered, even with official approval. Jung Ja-eun, from the Korean Red Cross, notes that life expectancy is 10 years lower in North Korea than in the South. “For second and third generations with families in North Korea, their need for reunions is much less,” she says. “But some younger generations will try to carry out their parents’ or grandparents’ last wish to meet their relatives in the North.”

Young Koreans understand that the act of reuniting separated families bridges only one tiny part of an ever-widening cultural, economic and political divide between the two Koreas. There will be issues to address in reunification said Kim Jae-yun. “Basic infrastructure such as roads, sewage, hospitals should be built in the North. This could lead to a tremendous economic burden on the South just as it did in Germany,” she said.

For those like Michael Lee, the family reunions epitomise the immense challenge ahead. “I think when these older people pass away the issue of reunification will still exist, but not because it’s a personally significant issue,” he says. “I think for a lot of people, the division is seen as a kind of historic injustice that Koreans as a whole have endured. If young people were presented with what was a simple solution to reunification, we would be more enthusiastic about it.” ■