Abacus | Libido, lost and found: why talk of Japan’s population decline is premature

The real trouble facing Japanese demographics is that Tokyo’s policies are inadvertently proving a remarkably effective contraceptive

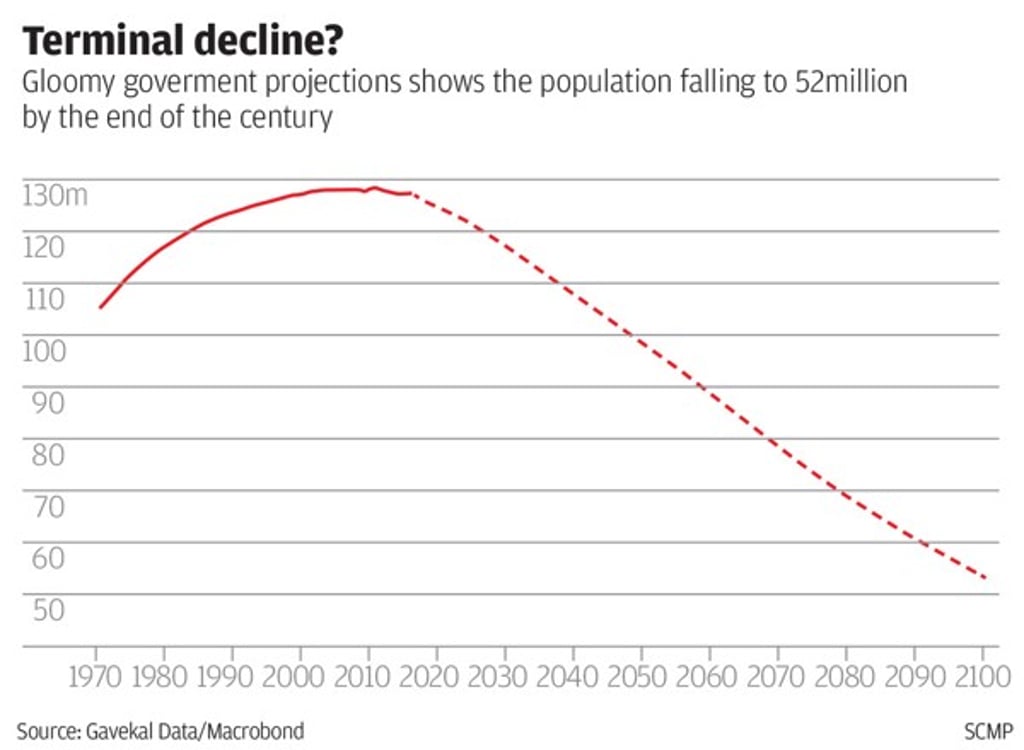

According to many, the long decay has already begun. Japan’s population peaked at just over 128 million in 2010. Since then, the combination of an ageing population and one of the lowest fertility rates in the world – on average a Japanese woman can expect to have just 1.45 babies in her life – has meant that deaths have exceeded births. With mass immigration ruled out by politicians and public alike, the result has been a fall in Japan’s population over the last six years of almost 1.3 million.

JAPAN’S MILLENNIAL MEN DON’T DRINK, DON’T DRIVE, DON’T WORSHIP WORK – WHAT DO THEY DO?

There’s just one problem. The stories about Japan’s lost libido are all wrong, and the population forecasts likely to prove misleading. Japan’s women would be very happy to have more babies – enough to sustain the population above 100 million and to keep economic growth in positive territory. The trouble is that the government’s own policies have inadvertently proved a remarkably effective contraceptive.