Exclusive | My mother and Mao, Singapore taxes and the rise of Hong Kong property: the Robert Kuok memoirs

In the debut instalment of six extracts from the first-ever memoir of Malaysian tycoon Robert Kuok, reproduced exclusively here, he recalls how mother shaped his views of China, and why he left Singapore and Malaysia for Hong Kong

Malaysian-born billionaire Robert Kuok has just published his memoirs – due out at bookshops this weekend – but they are by no means a tell-all. For starters he reveals few clues on the decades-old question of who will succeed him at the helm of the corporate empire he built from scratch in the post-war years. Still, the 376 pages offer a rare glimpse into the private life of a magnate, 94, who despite once owning the South China Morning Post is well known for having avoided the media limelight throughout his enigmatic rise from a small-time sugar merchant to becoming one of Asia’s richest and most influential people.

Kuok is among the handful of Asian magnates born in the early 20th century who, having steeled themselves from the horrors of war and the injustice of colonial rule, forged businesses that grew with the newly independent countries that replaced the vast Western empires.

Kuok, who was raised in Johor Bahru and emigrated to Hong Kong in the 1970s, gained ready access to the highest levels of power in these fledgling nations, from Singapore to Malaysia, Indonesia and China. But the book reveals how his heart still beats for Malaysia and his involvement in its early, post-independence politics.

China’s rise during Deng Xiaoping’s tenure as leader, and the country’s current transformation under President Xi Jinping are discussed at length by the tycoon, who built the World Trade Centre in Beijing and at one point helped China avert a sugar crisis.

Kuok proudly declares he “belongs” in Southeast Asia, but adds that he felt duty bound to help China, the birthplace of his parents, “wake up and join the modern world”.

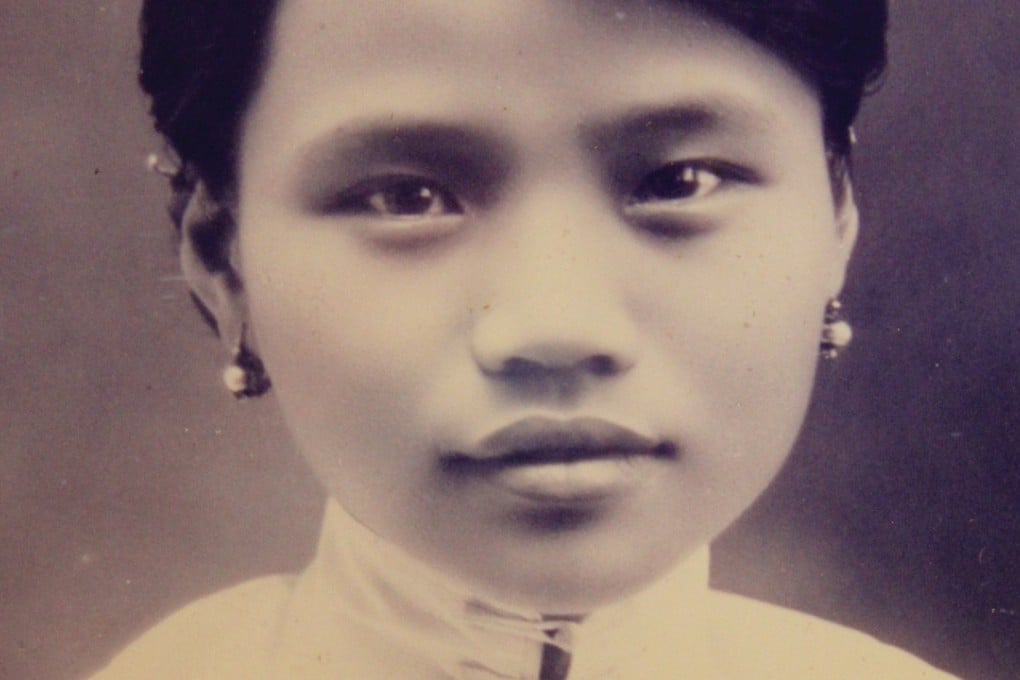

The book begins with a chapter on the lasting influence of his Fuzhou-born mother whom he calls the “true founder” of the Kuok empire and ends on the contemplative question of “What is wealth for?”. Kuok, the youngest of three brothers, details how his mother, Tang Kak Ji, shaped his views on everything from his love life to watershed boardroom decisions. The fiercely private father of eight for the first time also details the turmoil in his marital life.