Prem Tinsulanonda was a trusted royal aide. So who will be the new Thai King’s counsel?

- Prem, who died earlier this year, was a trusted adviser to the revered King Bhumibol and an influential figure in post-war Thailand

- Together, he and the King formed one of Southeast Asia’s powerful political partnerships. With a new monarch – King Vajiralongkorn – who might emerge to provide wise counsel?

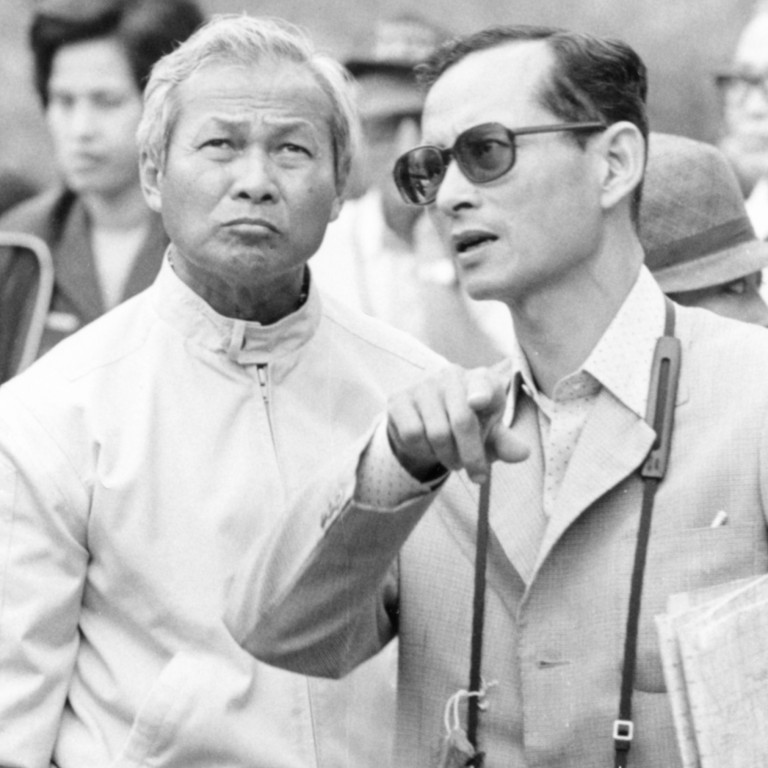

It is one of the most famous images in Southeast Asian history: Thailand’s King Bhumibol Adulyadej sitting regally before a group of prostrate, feuding politicians. It was May 20, 1992 and the king had just intervened, demanding an end to bloody riots that had paralysed Bangkok. The protesters dispersed, the junta leader resigned and Thailand gradually returned to civilian rule.

Also kneeling at the king’s side was another remarkable man: his trusted adviser Prem Tinsulanonda, who passed away earlier this year aged 98.

King Bhumibol was undoubtedly the defining figure in post-war Thai history, before his death in 2016 aged 88. The men behind him, though, such as Prem, were also immensely important in their own right.

There have been other intriguing and all-powerful political pairings in Southeast Asia: in Singapore, Lee Kuan Yew and Goh Keng Swee (the man behind the island republic’s economic success story); in Malaysia, Mahathir Mohamad and Daim Zainuddin.

By comparison, Indonesia’s Suharto – having risen to power in a coup – never trusted his lieutenants sufficiently to allow them the same authority.

Prem was born in the southern province of Songkhla in 1920. From a relatively humble background – his father was a prison warden – he joined the army before rising to prominence in his 50s as the cold war gripped the region.

As fate would have it, in the 1970s, Prem was commanding the Second Army in the restive north-eastern region of Isaan where the Communist Party of Thailand (CPT) was particularly active. He adopted a nuanced approach, granting amnesties and promoting grass-roots development.

Although he was not the mastermind of these initiatives, his success in Isaan brought a turning point in the struggle against the communists and a grateful monarch showed his appreciation by elevating Prem into his inner circle. Both men were soft-spoken, distrustful of politicians and intensely devoted to Thai tradition.

King Bhumibol found Prem to be an ideal right-hand man

Prem became the head of the Thai army in 1978 and then prime minister in 1980. Although he was never tested electorally, Prem governed with the backing of the palace until 1988.

He was neither a visionary nor a man of ideas but his resilience – he withstood two coup attempts – ensured a period of political calm that enabled the economy to boom. In 1980, Thailand’s GDP was US$32.35 billion but by 1988 had nearly doubled to US$61.67 billion.

Prem believed in empowering technocrats such as Snoh Unakul, his economic tsar. In turn, they ensured Thailand’s successful transformation from a predominantly agrarian polity into a manufacturing and export-oriented powerhouse.

“King Bhumibol found Prem to be an ideal right-hand man,” historian Chris Baker said. “Prem wasn’t so much a creative force in the construction of the ‘Bhumibol Era’; however, he was more an operational figure, and, in this respect, he was very important.”

Even after ceding power to an elected politician in 1988, Prem remained influential. He was appointed to the Privy Council and eventually became its president in 1998, holding the position until his death.

He cast a long shadow over the crucial events in the twilight of Bhumibol’s reign without ever appearing at the centre of them, as with the 1992 royal intervention.

When Thaksin Shinawatra was forced from office by a coup in 2006, Prem was regarded as the prime mover behind the scenes. After Thaksin’s sister, Yingluck, came to power in 2011, she called on Prem to pay her respects, like scores of other ambitious politicians or military officers.

In 2014, a second anti-Shinawatra coup ended Yingluck’s rule, plunging Thailand into the period of intense polarisation that continues to this day.

“Prem’s legacy is mixed,” said Dr Punchada Sirivunnabood, a political analyst at Mahidol University. “How Thais see him varies … the older generations remember him as a stabilising force in an uncertain era whereas younger Thais see him – fairly or unfairly – as embodying the elite repression of democracy.”

Prem derived much of his legitimacy from Bhumibol, allowing him to fend off political challenges and focus on the challenges of nation-building and consolidation as well as the promotion of the Chakri dynasty.

However, whereas Bhumibol’s prestige increased, Prem – and the Thai establishment in general – arguably failed to adjust to new social realities. Certainly, Prem’s insistence on a state rooted in the traditional principles of “nation, religion, king” no longer resonates with younger Thais seeking new ways to define their country and identity. Even worse, Prem’s preference for supposedly disinterested technocrats above elected politicians weakened Thai democracy.

He was both a fervent royalist and a builder, helping to steer the palace and Thai state through the political squalls of the cold war. With a new monarch on the Chakri throne – King Vajiralongkorn – it will be interesting to see who, if anyone, emerges to provide the wise counsel and steadying hand for the untested head of state, especially with a major economic downturn expected.

Modern Thailand remains, for now, the creation of King Bhumibol and Prem. But that may not be the case much longer.