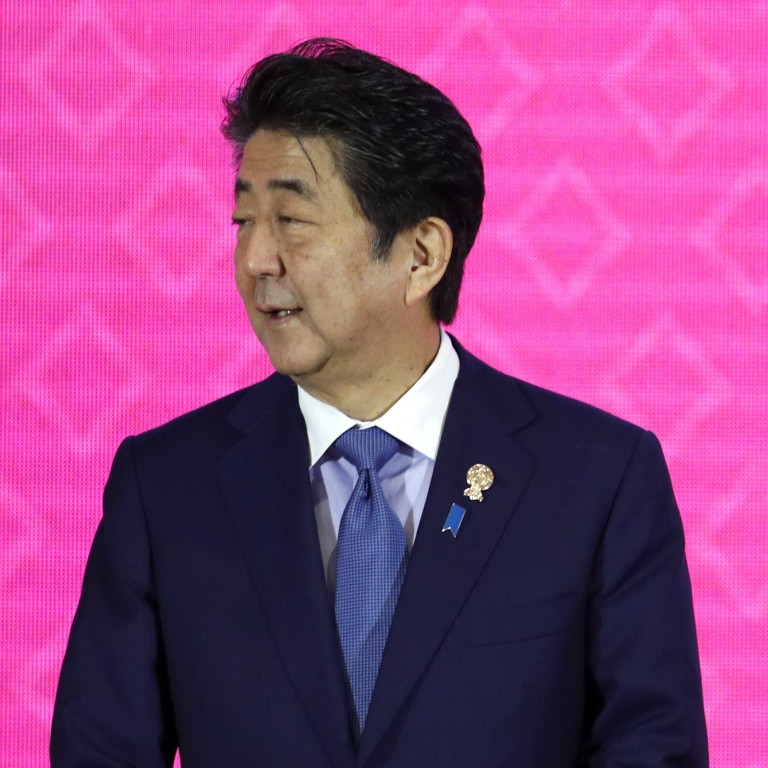

Abe is Japan’s longest-serving PM. Is that the extent of his legacy?

- The premier has broken a century-old record for political longevity – but despite domestic comebacks and foreign policy wins, a succession of scandals and his mixed results with the economy will live long in the memory

His first term in 2006-2007 was scandal-prone and shortened by illness. In a remarkable comeback, Abe resumed leadership of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) in September 2012 and returned to government, winning the national election that December.

Can Japan coax Southeast Asia into sticking by the rules-based order?

He called snap elections in 2014 and 2017 to take advantage of the perennial weakness and division among Japan’s opposition parties, who have consistently failed to offer any appealing policy alternatives. These victories entrenched his authority among the LDP factions, and ensured his re-election as party president in 2015 and 2018.

Assisted by a weaker yen, there have been monthly trade surpluses for most of the past three years, although none since July 2019. Record numbers of tourists have arrived, as Japan successfully hosted the 2019 Rugby World Cup, with the Tokyo Olympics to follow next year. Its export performance has boosted share markets and gifted high profits to large businesses, but this corporate largesse has not been passed down to workers. Wage growth was negative for most of 2019, and only reached 0.8 per cent in September; consumer confidence therefore remains stubbornly weak. The government plans to increase the country’s intake of foreign workers to supplement the shrinking labour market, where the unemployment rate is only 2.4 per cent.

What does Shinzo Abe’s name change have to do with unenlightened Westerners’?

During his most recent visit to the United States last September, Abe signed a limited trade deal covering agricultural products and digital services, but more contentious American tariffs on automobiles were not yet dealt with. Japan also played a lead role in salvaging the Trans-Pacific Partnership in 2016, after Trump withdrew the US from the regional trade agreement. An Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) with Australia was concluded in 2014, and an EPA with the European Union came into effect from this February.

Abe has also long maintained ambitions to revise Japan’s war-renouncing constitution. After the country’s cabinet reinterpreted Article 9 of the constitution in 2014, legislation passed a year later potentially allowing the Japanese Self Defence Forces to participate in military action with friendly countries, in scenarios of “collective self defence”.

The record defence budget for 2019 of Ұ5.32 trillion (US$48.9 billion) now ranks Japan as the eighth largest military spender in the world. Abe’s goal of a referendum for constitutional change appears less likely, though, after the LDP and allied parties lost their two-thirds majority in the Upper House elections last July.

Japan is the world’s fourth largest foreign aid donor, and Abe’s government has also encouraged more foreign investment and closer security ties with Asean, India and Australia. Ties with Japan’s largest trading partner China have improved, but relations with neighbouring South Korea have plunged to their lowest point in decades. Settlement of a territorial dispute with Russia also remains out of reach.

The gloss of Abe’s record tenure has been somewhat diminished after the justice and trade ministers resigned last month from his newly reshuffled cabinet for violating electoral laws by providing gifts to constituents. Abe was himself driven last week to cancel a publicly funded annual spring cherry blossom viewing party after it was revealed hundreds of political supporters from his own constituency had been invited.

Japan’s justice minister quits in second resignation to hit Shinzo Abe’s cabinet

These incidents – which recall previous nepotism scandals which have occasionally dogged Abe’s government – plus the ongoing tepid economy and likely failure to alter the constitution points to Abe being more likely to fulfil his promise to step down as LDP leader when his final term expires in September 2021. Party rules were changed at the 2017 LDP conference to allow Abe to seek one more term, and another alteration would be required for him to stay on until 2024.

Contenders are already looking towards Abe’s succession, such as his old rival, former defence minister Shigeru Ishiba; former foreign minister Fumio Kishida, and current defence minister Taro Kono. The charismatic new environment minister Shinjiro Koizumi may even seek to contest the leadership.

Nevertheless, the Abe era has nearly two more years to go, and so his record time in office is unlikely to be broken for a very long while.

Craig Mark is a professor in the Faculty of International Studies, Kyoritsu Women’s University, Tokyo