Is the coronavirus fatal for economic globalisation?

- The Covid-19 outbreak will foist profound changes on the world’s future development in terms of economics, society, diplomacy and geopolitics

- On top of this, the pandemic may also be a catalyst for restructuring global governance and supply chains

Covid-19 has already brought almost all the world’s major economies to their knees. The worst-case scenario is that it might bring about a global recession, as it has spread to more than 100 countries, and the human casualties and economic losses are still escalating.

Though the scale of its reach might be unseen in human history, the final toll in casualties and economic losses can be quantitatively measured once the outbreak is over. However, its longer-term consequences and fallout might not be so easily quantified, as the pandemic will foist inescapably significant and profound changes on the world’s future development in terms of economics, society, diplomacy and geopolitics.

Coronavirus: to Chinese democracy what Chernobyl was to glasnost?

With the pace of economic integration and globalisation in the past few decades, we all now live in a global village. Not only are our economies inextricably and inexorably tied together, but direct person-to-person contact is so frequent and intense that the world is all the more vulnerable to pandemics.

Though the novel coronavirus is thought to have originated in the central Chinese city of Wuhan, it has become a life-and-death fight between Mother Nature and human beings from any country. In this regard, the Covid-19 outbreak has raised serious questions about global public health security and the enforcement of health regulations around the world.

It is imperative that enforcement of global health regulations is strengthened, as many in the West believe China’s failure to implement some of the IHR requirements – such as transparency and the timely release of accurate information, at least in the early stages of the outbreak – was to blame for a localised health scare turning into a global pandemic.

Six ways the coronavirus crisis will change China’s relations with the world

The emergence of Covid-19 also suggests an urgent need for closer global cooperation in the research, development and production of quality, safe and effective medicines, such as the development of a life-saving vaccine. The world should work collectively to prepare contingency plans and maintain a store of emergency supplies and materials such as drugs, vaccines and masks, which are critical for developing countries with under-resourced health systems to cope with any outbreak.

The “once in 100 years” outbreak proves that pandemics are a challenge for humanity as severe and catastrophic, if not more so, as climate change, migration, drugs and terrorism.

As WHO director general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus warned recently: “Countries invest heavily in protecting their people from terrorist attacks, but not against the attack of a virus, which could be far more deadly and far more damaging economically and socially.”

The outbreak has also rekindled a debate about the advantages and disadvantages of economic globalisation. The huge losses it has caused around the world have come at a fraught time when policymakers are struggling to divert a downward trend in the global economy, which is operating dangerously close to a stall speed and riddled with imbalance, high levels of indebtedness and asset bubbles.

Forget Sars, the new coronavirus threatens a meltdown in China’s economy

For China’s trade partners, the pandemic has exposed the downside of overreliance on Chinese supplies. Many companies have come to realise the risks of depending on a single country. Manufacturers worldwide have become more reliant on China’s factories for many intermediate products, given the country’s increasing role in this regard, with a 32 per cent share of the global total. Industries that rely on China’s supply of intermediates – including hi-tech products, consumer electronics and smartphones – have been hardest hit.

Cars and pharmaceuticals have suffered less as they are moderately exposed, while traditional industries such as clothes, shoes and toys are at a lower risk as their production has already been shifted away from China. However, many foreign manufacturers who are dependent on Chinese components, parts, materials and expertise have not been spared.

Last month, a few weeks after Beijing locked down a dozen cities in Hubei province, a Dun & Bradstreet report suggested 938 of the Fortune 1000 companies had a Tier 1 or Tier 2 supplier that had been affected by the epidemic. Economic globalisation has traditionally been designed to promote economic efficiency as it optimises cost competitiveness, but the outbreak underscores the risks of competitiveness as well.

The coronavirus threatens the Chinese Communist Party’s grip on power

As the pandemic will compound price pressures and weigh on corporate profit, business executives will refocus resources on searching for substitutes or diversifying supply. But Covid-19 does not just suggest a contained supply shock from China, but also an unrestricted shock to entire global supply chains. Thus the decentralisation of production might reshape the global economy as well as force the restructuring of supply chains.

Companies, multinationals in particular, might adjust their business and investment strategies and governments might adjust their macro policy in their responses to the outbreak.

With such considerations, the economic globalisation of the past few decades might be slowing, if it does not die down. And worse, Covid-19 might strangle the global supply chain.

The outbreak has already caused a global health crisis, travel restrictions, logistical and production disruptions, financial panic and economic woes. On top of this, rising diplomatic tensions and political debate due to the pandemic might suggest more significant and profound reforms will emerge in the future, in terms of overhauling economic globalisation, restructuring global governance, and reshaping geopolitics. ■

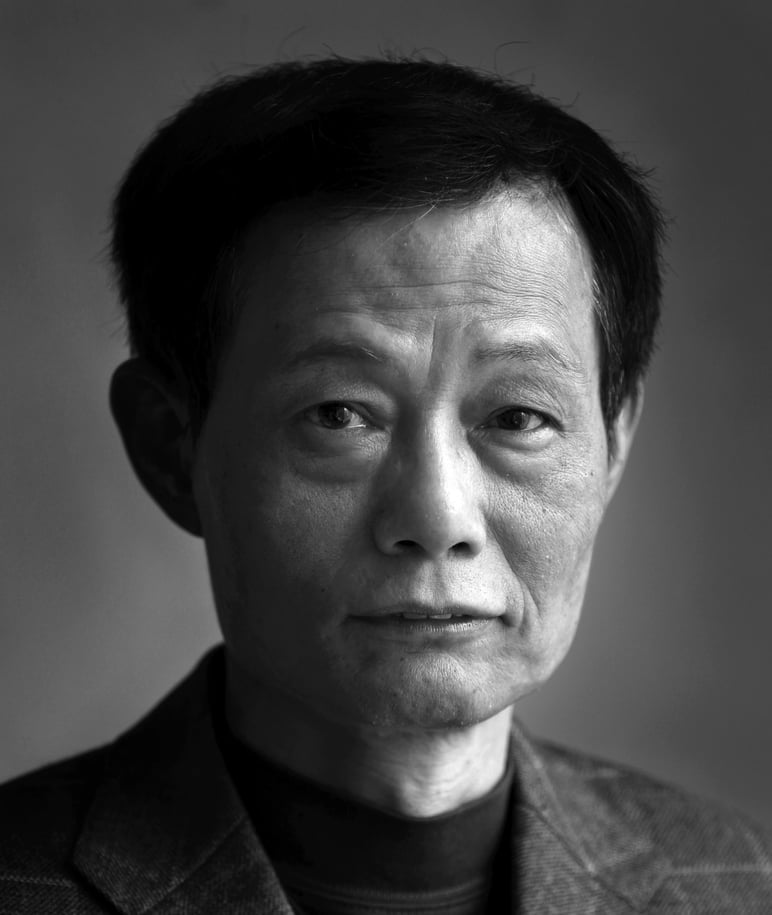

Cary Huang is a veteran China affairs columnist, having written on the topic since the early 1990s