China has a privacy problem. New data laws could help curb the worst abuses – but not all of them

- From pinhole cameras in hotel rooms to undeclared facial recognition cameras in shops, there is a thriving industry in China that makes money from blatant invasions of privacy

- A draft Personal Information Protection Law and other legislation should help combat the problem – but don’t expect it to trump national security or business interests

Fans of James Bond will be familiar with scenes showing the British spy sauntering into a hotel room, before looking around and using a handheld counter-intelligence device to sweep for bugs and hidden cameras.

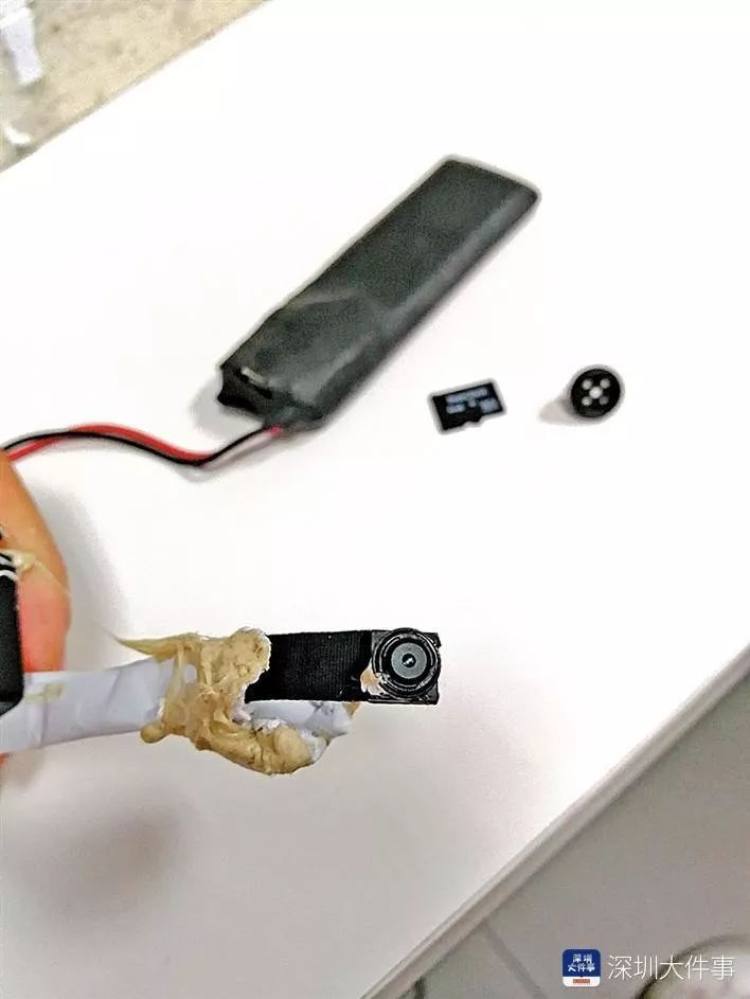

One of the most egregious examples of this came to light late last month, when a Guangdong TV report revealed the story of a young couple in Shenzhen, who had been living in their rented flat for six months before they discovered the pinhole camera hidden in their bedroom’s air conditioning unit.

Britain has criticised Beijing’s changes to the Hong Kong electoral system – but it also inspired them

The shocked couple were reportedly so fearful of what might happen next that they chose not to report the incident to the police, instead completing a thorough scan of their next rental home before moving in.

Their traumatic experience is sadly not unique. An investigative report published on Tuesday by a newspaper in Shandong uncovered a sophisticated network of criminal enterprises that build, modify and install pinhole cameras, the footage from which they upload and sell online. For just 188 yuan (US$29), an undercover reporter was given access to live-stream video feeds from 30 homes at once, with the option to specify hotel rooms, shop dressing rooms or beauty parlours for a slightly higher fee. The report did not say if the police had been informed.

Data leaks are significant. For a few hundred yuan, the personal details of hundreds of thousands of people can be bought – including their ID numbers, driving licences, phone numbers and addresses.

Rising public concern has finally prompted the central government to act on the issue after years of dragging its feet. Last October, the National People’s Congress, China’s top legislature, released a draft of a Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL) for public comments. The authorities reportedly put together a team of lawyers to explore drafting the PIPL as early as 2003, but only really put their minds to it over the past few years.

Tough rhetoric at the US-China talks sets the tone for future ties: clashing as a rival, and working as a partner

The PIPL has been billed as the country’s first dedicated omnibus law to address the personal data rights of individuals, and is modelled after the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation – widely considered to be the toughest privacy and security law in the world.

It seeks to regulate the collection, storage, use, processing, transmission, provision, and disclosure of personal information by organisations and individuals.

The PIPL – along with the China Cybersecurity Law that took effect in 2017 and the draft Data Security Law – will herald the dawn of a new data protection regime in China, according to official media.

So far, the public’s attention has mainly focused on how the draft PIPL will be applied to companies’ commercial collection and use of personal information – a key area of concern.

What has been less discussed is the challenges of enforcing the law as it applies to government departments.

Like all governments, China collects and creates huge amounts of data in the name of national security, public safety, social control, and other purposes.

Much has been written about its successful creation of a surveillance state in the name of national security, with tens of millions of cameras now located across the country.

While this has raised international alarm, many people in China seem unperturbed – the general impression being that the security cameras have indeed helped cut crimes and enhanced their sense of security.

In Hong Kong, can you be a patriot and criticise the Communist Party? Definitely

This may be somewhat true, but it has also helped create a myth that the Chinese people don’t care about what is done with their personal data.

In 2018, Robin Li, CEO of Chinese technology giant Baidu, created an uproar on social media by suggesting that Chinese people were not sensitive about privacy and were willing to exchange it for safety, convenience and efficiency.

In the wake of the outcry, Li retreated from his claim and has since started to call for better protection of data – but his remarks reflect the prevalent thinking of many Chinese officials and tech executives whose business depends on commercialising the collection and use of data.

Public concern has been on the rise in recent years, however, over the excessive harvesting, illegal sale, and leaks of data by both the authorities and companies.

But now that the authorities have brought the pandemic under complete control within the country’s borders, considerable worries exist that some, if not all, of those “extraordinary measures” are here to stay permanently – representing a serious escalation of government intrusion into private lives.

On a recent spring excursion to the Great Wall at Mutianyu, for example, this writer was required to provide not only his health code on a mobile phone app, but his travel document and phone number as well.

China walks fine line between stoking nationalism and seeking global engagement

The government’s cavalier attitude towards data protection has emboldened companies in their over-collection and abuse of personal data.

For instance, in an annual broadcast last month to mark World Consumers Rights Day, state broadcaster China Central Television called out German bathroom fixtures brand Kohler and carmaker BMW for using facial recognition technology on visitors to their shops without their knowledge.

The reality is it’s an open secret that a wide range of Chinese and foreign companies have employed this technology on their customers without telling them.

When PIPL goes into effect, sometime later this year or next, it may help curb some of China’s most widespread privacy abuses – but don’t hold out hope it will address the significant imbalance where national security and business interests are concerned.