Philippine ‘superwoman’ smashes religious, gender stereotypes to resolve conflicts – with help from her daughter

- Hardly any women work in conflict resolution in Asia, but Connie Dumato and her daughter show how female-led mediation can make a difference

- As Asean prepares to launch a regional framework on promoting women’s role in peacebuilding, their reconciliation efforts are in the spotlight

“This was a very traumatic experience,” said the 62-year-old Muslim woman, recalling hearing gunshots ricocheting through the streets.

Dumato described it as a “community war” in which “people were killed by the military and the ‘Ilagas’”, a Christian extremist paramilitary group that led a series of attacks in the 1970s.

By age 14, Dumato had become more deeply engaged in the conflict. “I was on the front lines holding my medical kit,” she said. “I had no option but to get involved.”

Today, Dumato is a retiree who devotes her time to conflict mediation and advocacy work in the southern Philippines, which has been plagued by poverty, insurgencies, and endemic violence for years. With the help of other women and her own children, she has harnessed her experience of conflict to bring peace to the communities who have sought her help.

And she’s not alone – an increasing number of women in Southeast Asia are taking part in peacebuilding efforts, although the importance of their contributions are seldom fully recognised.

Why Asia should be concerned about Big Tech failing women

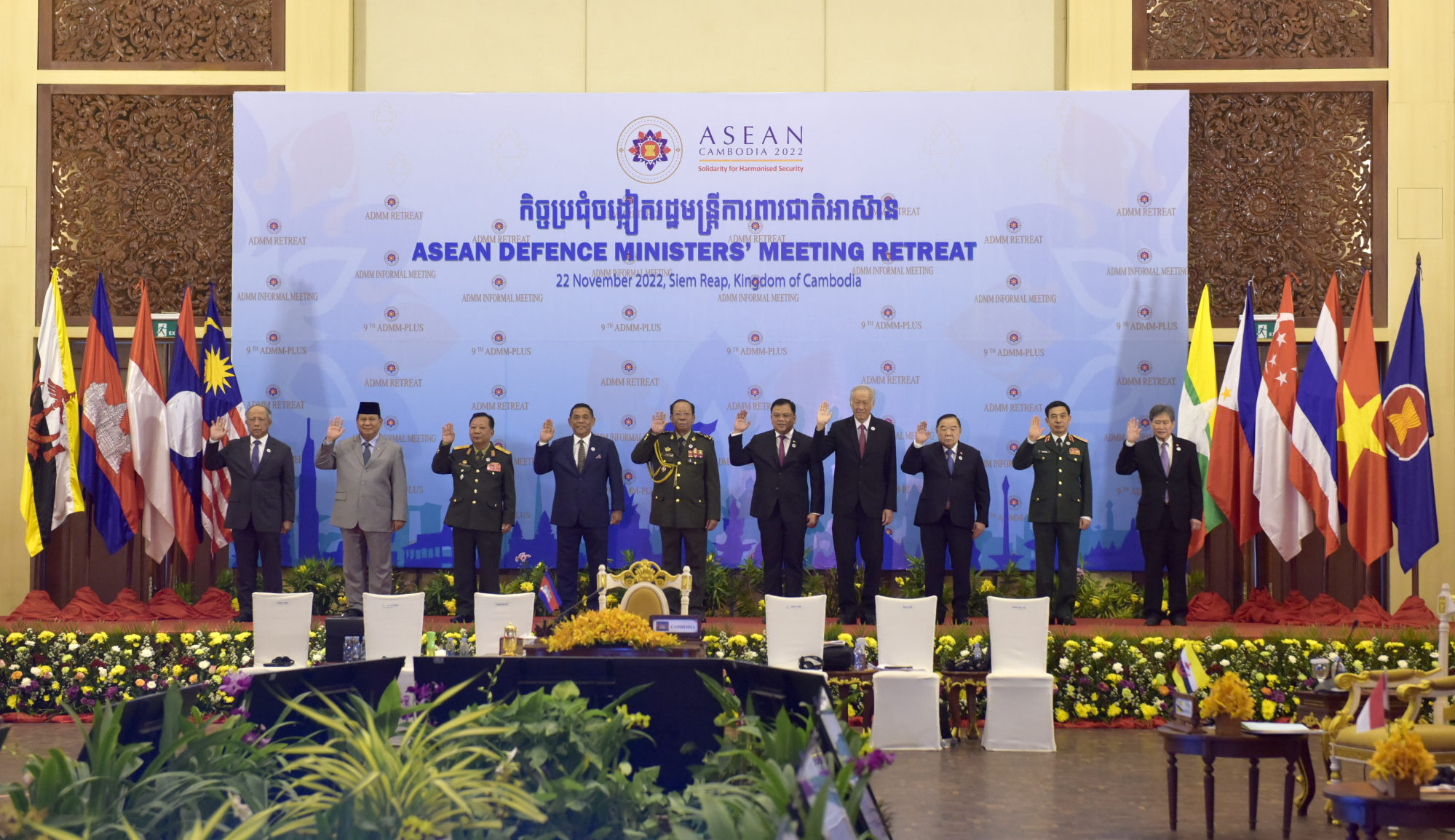

The plan aims to provide a regional framework for the bloc’s 10 member states to implement activities that further promote women’s representation and participation in peacebuilding.

“Challenges are everywhere, but although I have encountered many, I have proved that all the work can be done by women like me,” Dumato said. “There is no impossible.”

An accredited court mediator and former stenographer, Dumato is currently the president of mediation group Tupo na Tao sa Laya-Women – or TTLaW – which was founded in North Cotabato in 2020.

The group operates in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao, where it has dealt with complex conflicts such as clan feuds – known in the Philippines as rido – murders, separations and land disputes, as well as political and leadership conflicts.

An increase in rido conflicts – often fuelled by politics – has been recorded by experts on the ground, highlighting the need for mediators like Dumato. Many of those who live in Bangsamoro territory lack access to basic services such as education.

“In my community the main issue is poverty,” said Dumato, who in the past three years has mediated more than 30 cases. “The killings usually start with an ambush, like snatching of the motorbikes that they ride. But many conflicts are deeply rooted – maybe it’s about leadership, a land grab … Everybody wants to become a leader.”

The Moro people of the southern Philippines – as Muslims were so named by Spanish colonists – have long fought for self-determination, both against US occupiers and later the independent Philippine state. Bangsamoro, which literally means “nation of Moros”, has been used by many to describe both a collective identity and also a territory that is home to different communities.

A historic peace agreement reached in 2014 between the Philippine government and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front, the country’s largest Muslim separatist group, paved the way for an end to decades of conflict, which had killed more than 120,000 people and displaced an estimated 2 million.

In exchange for decommissioning their weapons, the rebel group was granted permission to set up an autonomous government to run parts of the southern island of Mindanao. The region’s first parliamentary elections are now scheduled for May 2025.

When women lead the peace process

Filipino political-science professor Miriam Coronel-Ferrer signed the 2014 peace deal with the Muslim separatists on behalf of the Philippine government. In doing so, she became the first female chief negotiator in the world to sign a peace accord with a rebel group.

This shows “what can be achieved when women lead peace processes”, said Sarah Knibbs, regional director for UN Women Asia and the Pacific, which has provided training to women on issues such as conflict analysis.

She noted that peace deals involving women were 35 per cent more likely to last at least 15 years. But although women have played a crucial role as peace leaders in the region, their involvement remains limited and has come with plenty of challenges.

As Dumato rose to more prominent roles, many – men in particular – have questioned her ability. “Do you believe Connie can handle the job?,” Dumato recalled hearing some asking.

I always find a way to let them know that women know something that men don’t

“They didn’t like me because I am a woman … Women are not allowed to hold a position that ‘underpowers’ men in the community,” she said.

Negative comments haven’t dissuaded her, however – quite the opposite, in fact.

“I always find a way to let them know that women know something that men don’t,” Dumato said.

“Women in my community complain they are left behind by progress and development. And that is true … I am encouraging them to participate, I help them to organise themselves … so they can be seen.”

Filipino women voice out stresses of being the firstborn daughter

Knibbs said “Filipino women are courageous” and have become more visible in society. “But we do also see the risk of backsliding of women’s rights, including a belief in the primacy of hard power, and tolerance for [the] oppression of women and gender-based violence especially in conflict-affected areas,” she said, noting that women’s endeavours are often relegated to the periphery.

“Women’s work in peacebuilding on the ground tends to be limited to providing care and relief during displacement,” she said, adding that it’s still “uncommon to find women in key decision-making roles on matters of peace and security”.

Research has shown not only the disproportionate impact of conflict on women and girls, but also their critical role in promoting peace.

Yet there is still the need for a “wider recognition” that “sustainable peace is impossible without women’s formal political participation”, said Soumita Basu, associate professor at the South Asian University’s department of international relations.

“Generally speaking, a regional plan is a welcome step forward,” she said, adding that it “also bolsters existing consensus on war, peace, and security issues in the region”.

Basu said the Asean plan being launched on Monday highlights the role women can play in tackling both traditional security challenges like armed conflict as well as emerging threats to health and well-being, such as Covid-19, climate change, human trafficking, and violent extremism.

According to the plan, adopted by Asean leaders last month, an effective response to security challenges relies on the capacity “to address the needs of all in society, and to that ensure women, who are often on the front lines of response, are fully included within and leading efforts to design and implement solutions”.

Aurora de Dios, senior project director of the Women and Gender Institute at Miriam College in the Philippines, said she was cautiously optimistic about the impact of the Asean plan, as many member states haven’t yet developed their own national plans.

Asean women led the way in trade talks. Are they better negotiators than men?

“There is always a gap between endorsement and implementation. But the plan is a reference point, even if it’s not implemented fast enough or not implemented at all,” she said.

De Dios said the most important factor for policy implementation was each country’s political climate and the ability of their respective governments to cooperate and accept suggestions from civil society.

“That is possible in some Asean countries, but not all,” she said. “If there is no democratic space for NGOs and if critical partners from the community are excluded, the implementation is going to be problematic.”

Overcoming anti-Muslim stigma

In the 20 or so years Dumato spent in Manila before moving back to her home province, she said she felt the stereotypes attached to being a Muslim woman – including being wrongly labelled as a member of Abu Sayyaf, an extremist group known for bombings and kidnappings.

“I would feel angry because I felt I was being oppressed, because I am a Bangsamoro, because I am a Muslim. Immediately my instinct was to reply and fight back,” she said. “But I started reviewing myself … I told myself that not everybody was my enemy. While it’s true that many Christians oppressed my relatives … of course, I had to be fair. Not everyone had done that.”

The National Commission on Muslim Filipinos, a government agency, estimated in 2012 that nearly 11 per cent of the country’s population were Muslim – most living in Mindanao.

Dumato noted that violent groups such as Maute and Abu Sayyaf do not represent people living in local communities.

“We Bangsamoros have thought a lot [about] how to avoid, prevent, and protect our community from being involved with those kinds of people,” she said.

Despite deeply ingrained stigma, coupled with the negative impact of the Marawi siege, Dumato said discrimination against Muslims had actually dwindled over the years.

“There are still stereotypes against the Muslim community … women and children are [still sometimes] ordered to remove hijabs,” she said. But “the discrimination is not the same as before, we are enjoying the gains of the peace processes.”

Dumato’s 27-year-old daughter Princess grew up aware of the cultural differences between her and most of her school friends who were Catholic.

But Princess said she led a “normal life” as a teenager, although she felt better understood in her home province than in Manila. “People here [in North Cotabato, Mindanao] know that … just like any other religion there are good and bad people.”

Daughter to a ‘real-life superwoman’

Today, Princess – who works as a teacher at a public primary school as well as the youth head at TTLaW – regrets that there is still too much violence in Mindanao.

“Every day, I have a fear that someone will be shot behind me and a bullet will hit me,” she said. “It’s so easy to just kill someone here. Like over a misunderstanding, a traffic collision, they will kill you and threaten your family.”

Princess has focused on working with marginalised youngsters and sometimes joins her mother in mediation sessions. “I document what she does and work on proposals,” she said.

She said she was particularly concerned about her mother’s safety when she mediated a case involving two major armed groups.

From Indonesia to Pacific, women have borne brunt of pandemic challenges: UN

“I thought she could be shot by those people. They were not accepting the agreement and I was telling her to stop because I was afraid for her. It took about six months for it to be resolved,” she said. “She really risked her life to mitigate the situation and prevent conflict.”

Princess and her two brothers grew up in a house full of people who were supported by their mother. “She always said: ‘You need to help people, they would not be here if they did not need us’. I realised then that she was a real-life superwoman,” Princess said.

“There is a part of me who wants to be like her, although I am scared of what she does.”

Princess, who is herself a mother to a six-year-old girl, vowed to continue doing her bit to show that women are leaders – not just wives and mothers. She noted that new generations understand that women can “be providers, achievers, and a tool for peace in Mindanao”, but a lot still needs to be done.

Knibbs said that while there are armed conflicts that persist in Mindanao, “stronger incorporation of gender perspectives is needed for the prevention of violent extremism”.

In addition to being home to Asia’s longest-running insurgency, the Philippines is also one of the most disaster-prone countries in the world, which has led to large-scale displacement that leaves women and girls at greater risk.

“It is essential to address the impact of armed conflicts and natural hazards on women while recognising their critical contributions to peacebuilding,” Knibbs said.

She added that it’s important “to continue to empower women and their organisations” and “keep pushing back against the force of patriarchal tendencies of some of those in power and in some aspects of culture and norms”.

How Asia’s women have triumphed even in face of adversity

Princess said women in her province not only need financial support, but also education and an avenue through which they can express themselves and take part in peacebuilding solutions.

“We need to travel to different parts to solve more conflicts without the use of guns and bombs,” she said. “The vision of TTLaW is not just training women in mediation, it’s also training women to be actually involved and immersed in different sectors.”

Her mother said she also believes the secret to peace is education.

“My dream for the community is that every young individual should be sent to school,” Dumato said. “It’s my dream to see my people, these young generations sitting there in peace and progress, with no more fear of wars or food shortages.”