What’s behind crown prince’s crackdown in Saudi Arabia - and where will it lead?

To loyal Saudis, the crown prince is courageously taking on corruption. To sceptics, he’s indulging in a power grab that could inflame tensions. Whoever is right, Saudi Arabia will never be the same

Life in Saudi Arabia is very different today from what it was a few weeks ago – not on the streets or in the markets, where activity is normal, but in the way the kingdom does business and governs itself.

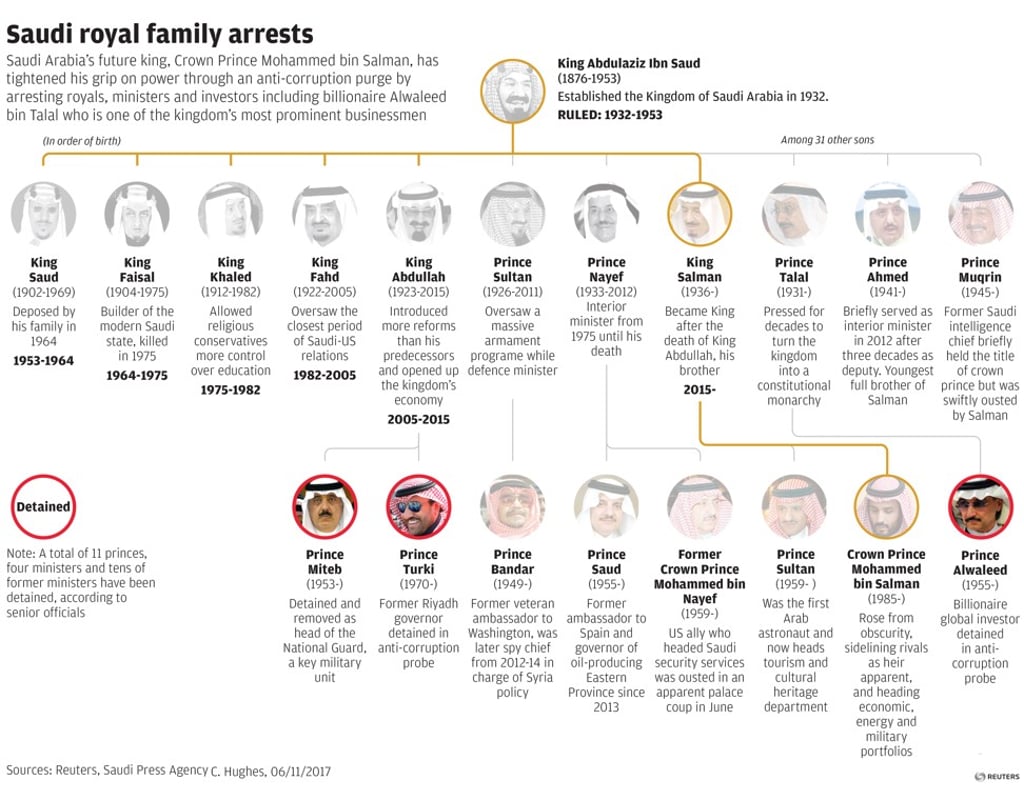

With astonishing speed, the headstrong young crown prince, Mohammed bin Salman, has seized control of almost all levers of power in his country and disrupted patterns of governance and commerce that had been in place for decades.

At the age of 32, he has shunted aside all potential rivals, gained control over the armed forces and security services, taken charge of economic planning and oil policy, instituted a more muscular foreign policy and altered the line of succession to the throne. Not since the reign of King Abdul Aziz, who founded the modern kingdom in 1932, has one member of the al-Saud family wielded such uncontested power.

To his supporters, mostly Saudis, his stunning moves, including the arrests of princes and billionaire tycoons, represented a long-overdue shake-up of a feudal system that was choking on corruption and incompetence, and was no longer sustainable. Those arrested and dismissed from their positions apparently submitted without protest, reflecting the fact, as one Saudi analyst said, that “those old rich guys have no constituencies” except each other. He described the arrests as “shock therapy” for a sclerotic system. The message to the sprawling royal family is “no more parasites”, he said.

To outside analysts, including many with long experience in Saudi affairs, it appears that the prince has staged a power grab that could threaten the kingdom’s stability, discourage foreign investors, and exacerbate the rivalry between Saudi Arabia and Iran that has inflamed tensions across the Middle East.